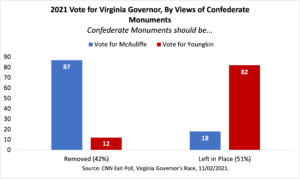

In the politico world, all eyes were on Virginia last week. Despite obsessing over every pattern in the tea leaves left from the expended campaign strategies and discernible in the exit polls, one striking finding was almost entirely missed by the punditry class: how strongly views about Confederate monuments divided Virginia voters.

- Among the 42% of Virginia voters who believe Confederate monuments should be taken down, nearly nine in 10 (87%) voted for the Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe.

- Among the 51% of Virginia voters who believe Confederate monuments should be left in place, more than eight in 10 (82%) voted for Republican candidate Glenn Youngkin.

Not surprisingly, attitudes about Confederate monuments are highly stratified by racial and religious identity. A 2018 PRRI national survey found that nearly three-quarters of white Americans say Confederate monuments should be either left in place with a plaque placing them in historical context (49%) or left as they are (24%), while two-thirds of African Americans say they should either be removed and relocated to private property (40%) or removed and destroyed (27%).

And as I showed in White Too Long, in national data, eight in 10 or more of white evangelicals (85%), white mainline Protestant (85%) and white Catholics (80%) believe Confederate monuments are more a symbol of Southern pride than racism, a view shared by far fewer (54%) religiously unaffiliated whites and only 24% of African American Protestants.

To put this finding into perspective, the divide over Confederate monuments rivals the stratification produced by abortion, an issue typically considered the bellwether of partisan polarization. Among those who believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases, 73% voted for McAuliffe, while 87% of those who believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases voted for Youngkin.

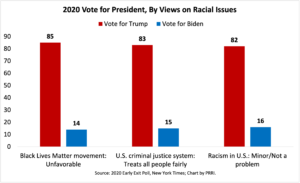

The power of racial attitudes also was clear, and little discussed, in the 2020 presidential election exit polls. Among voters who hold an unfavorable view of the Black Lives Matter movement, believe the U.S. criminal justice system treats all people fairly, or believe that racism is a minor problem or not a problem at all, more than eight in 10 voted for Donald Trump. At the national level, the divides produced by these attitudes are stronger than the divides over abortion. Among those who believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, 76% voted for Trump.

Earlier this week, in The New York Times “Morning Report” newsletter, David Leonhardt drew on PRRI’s recently released American Values Survey to explore the challenges Democrats have had reaching white working class (and I would add white Christian) voters. In a section headed “Culture over Money,” he wrote:

Democrats often lament that so many working-class Americans vote against their own economic interests, by supporting Republicans who try to cut health care programs, school funding and more. A 2004 book summarized the liberal frustration with the title, What’s the Matter with Kansas?

Leonhardt helpfully went on to note that white working-class Americans “are hardly the only voters who prioritize issues other than their financial situation.” In Virginia, wealthy areas like Arlington — where household incomes are commonly six or even seven figures — McAuliffe won 77% of the vote. These voters knowingly cast their ballots for the party most likely to raise their taxes.

I’ve always thought the “What’s the matter with Kansas?” thesis — or at least the cocktail party version of the book’s thesis that was so seductive to so many progressives — was condescending and wrong-headed. The assertion that people vote “against their interests” is offensively paternalistic. It betrays a lack of intellectual curiosity that fails to imagine that “interests” can be racial and religious and cultural and not just material.

“The divide over Confederate monuments rivals the stratification produced by abortion, an issue typically considered the bellwether of partisan polarization.”

As someone who grew up as a Southern Baptist on the white working-class side of town in Jackson, Miss., it always was implicitly clear that status, the sense of one’s place in the community and in the country, was not primarily about money.

In recent years, public opinion surveys have been clearly telling us that our two political parties are polarizing not over competing economic visions but over disparate visions of American identity. Today, the parties are more divided over the changing demographics of the country, and the place of the former white Anglo-Saxon Protestant ethnoreligious majority in it, than over economic policy.

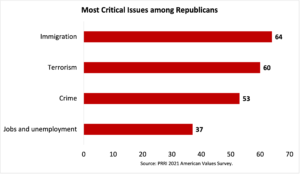

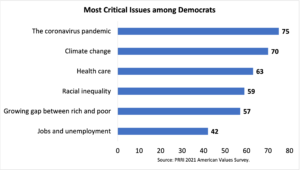

For example, historically, when pollsters have asked about voter priorities, economic issues typically topped the list for both Democrats and Republicans. But even with the pandemic economic crunch and current concerns about inflation, PRRI’s just-released American Values Survey found that neither Republicans nor Democrats rated “jobs and the economy” highly among a list of 10 potentially critical issues (only 37% of Republicans and 42% of Democrats said it was a critical issue). But if you look at the issues partisans do say are critical, identity issues come clearly into focus.

There are only three issues, for example, that a majority of Republicans see as critical issues to them personally: immigration (64%), terrorism (60%), and crime (53%). White evangelical Protestants, who comprise the base of the GOP, largely share this perspective, although only two issues reached majority as critical issues: terrorism (57%) and immigration (54%), with crime slightly lower at 46%.

In the context of other findings in the survey, it’s clear that these priorities are fueled by a sense of threat to a white Christian American majority. These critical issues translate into fears about the rising number of Latino Americans, fears about Islam, and anti-Black attitudes tied to a “law and order” mentality where African Americans are associated with criminal activity and lawlessness in major cities.

You won’t need to search far to find each of these interpretations made painfully explicit in former President Trump’s speeches and in the content of the 2016 and 2020 Republican National Conventions.

And there is a more significant piece of supporting evidence that ethnoreligious identity is becoming the primary battle line in the culture war: Only about one-third (36%) of Republicans and less than half (48%) of white evangelical protestants said abortion was a critical issue to them personally.

By contrast, there are five issues — none of which are shared with Republicans — that Democrats say are critical to them personally. The coronavirus pandemic (75%) and health care (63%) are highest on the list for Democrats, along with climate change (70%). Nearly six in 10 Democrats also highlight racial (59%) and economic (57%) inequality as critical issues.

Even in my best attempt to read this data with nonpartisan lenses, it’s difficult not to discern two very different, incompatible visions for the country: A Republican vision that is increasingly based on protecting a white Christian America against perceived outside threats and a Democratic vision that is becoming focused on bridging the divides within an increasingly diverse country. The PRRI team attempted to capture this dichotomy in the title of the American Values Survey report this year: Competing Visions of America: An Evolving Identity or a Culture Under Attack?

Despite the clear turn to identity — particularly the status of white Christian identity — as a driving force in our country’s political divides, there remain prominent voices encouraging Democrats to look past this moment of reckoning on racial justice and inequality to focus on economics.

James Carville — political strategist for Bill Clinton known for his famous campaign dictum, “It’s the economy, stupid” — gave a blunt explanation to PBS’s Judy Woodruff for the Democratic losses in Virginia last week:.

“It’s difficult not to discern two very different, incompatible visions for the country.”

Well, what went wrong is this stupid wokeness. All right? Don’t just look at Virginia and New Jersey. Look at Long Island, look at Buffalo, look at Minneapolis. Even look at Seattle, Wash. I mean, this defund the police lunacy, this take Abraham Lincoln’s name off of schools, that — people see that. And it’s just — really have a suppressive effect all across the country to Democrats. Some of these people need to go to a woke detox center or something. They’re expressing language that people just don’t use. And there’s a backlash and a frustration at that.

I agree with Carville that “defund the police” has been unhelpful — it’s neither a savvy political slogan nor an accurate depiction of what most police reform advocates actually want to do. But pretending that the tactics of the 1990s — which saw economic successes but also Democratic President Bill Clinton backing a crime bill that contributed to mass incarceration of young Black men — are the solutions for today is a mistake. Such a strategy misreads both the signs of the times and the implications of the data. And more critically, it ducks our moral responsibilities.

If we really want to heal the soul of the nation and achieve our country, we can’t continue to paper over racial injustice with economic policy. “It’s the culture, stupid” — or less euphemistically, “It’s the white supremacy, stupid” — must be the new mantra of political analysts today.

Robert P. Jones (Photo by Noah Willman)

Robert P. Jones is CEO and founder of PRRI and the author of White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, which won a 2021 American Book Award.

This column originally appeared on Robert P. Jones’ substack #WhiteTooLong. In partnership with the author and PRRI, each Monday BNG will feature a new column from Jones.

Related articles:

Survey paints scary, hopeful picture of U.S. political divide

Why the U.S. is uniquely divided: Engaging a scholar from New Zealand | Opinion by David Gushee

How you view police killings, racism and monuments influenced by faith and party