As the pandemic subsides, I cannot help thinking about the tragedy and loss of lives. It is painful to think that during the pandemic, about 18.2 million people died worldwide, including about 1.13 million Americans. These are startling numbers, and the loss of lives is distressing.

The pandemic has been difficult for all of us. However, it has been deeply grievous for Asian Americans. Another alarming fact is the increase in hate crimes committed against Asian Americans. According to data released by the FBI in 2021, hate crimes against Asian Americans rose 76% during the pandemic in 2020 compared to 2019. Many of these crimes were directed toward women and elderly women who were walking home or going about their daily tasks. Unprovoked hate crimes against Asian Americans have been recorded on cell phones and cameras.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim

If we examine American history, it is easy to see that hate crimes toward Asian Americans have been committed since the beginning of Asian migration to America. For example, one of the largest mass lynchings in America was committed in Los Angeles’ Chinatown on Oct. 24, 1871, when 500 white and Latino rioters attacked, robbed and killed Chinese residents. Seventeen to 20 Chinese immigrants were tortured and hanged by the mob. Another part of this horrific tragedy was that only 10 people were tried in court and of these only eight were convicted and sentenced. However, their convictions soon were overturned on a legal technicality. Therefore no one paid for this atrocious crime against Chinese Americans.

Asians who were indentured servants (known derogatively as “coolies”) endured the hardships of long hours and poor treatment. They were essentially contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years to help pay off a debt incurred or to pay the cost of transportation to America. The debt often was huge, and it was difficult for Asians to repay. Furthermore, Asian labor became a commodity, and many men worked in harsh conditions like the sugar industry in Hawai’i or in building the Transcontinental Railroad.

“Asians were hated because they were supposedly taking jobs and carrying disease strains, and thus people began to fear them.”

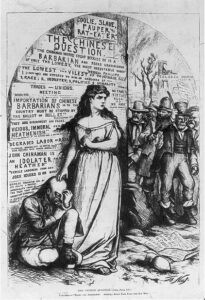

Asians were hated because they were supposedly taking jobs and carrying disease strains, and thus people began to fear them. Therefore, in 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed an “anti-coolie” bill that banned potential Chinese workers from being transported in ships owned by Americans. The increase in fear also led Congress to sign the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that prohibited Chinese workers from entering the U.S.

1871 cartoon “The Chinese Question”

Chinese people already on the mainland were hired to work under harsh and brutal conditions on the railroad, where they were assigned dangerous tasks such as blasting tunnels through the granite and were paid far less and given no food while the white workers were given food and paid more.

Hatred, racism and xenophobia against Asians were high, and this led to other hate crimes, including the Japanese internment during World War II. In this shameful incident that stains U.S. history, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, many of whom were U.S. citizens, were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in concentration camps on the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Asian Americans have been considered “perpetual foreigners” and have not been accepted as “true” Americans. This and other racist understandings, such as falsely referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese Flu,” perpetuate discrimination and xenophobia against Asian Americans. The list keeps growing, and it is long overdue to stop these hate crimes from being committed against Asian Americans.

“One way to begin to view Asian Americans favorably is to understand their rich and important influences on American society.”

One way to begin to view Asian Americans favorably is to understand their rich and important influences on American society.

May is AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) Heritage Month, and much of society is unaware of this important month that celebrates many of the contributions to America by AAPI individuals, communities and organizations. The first celebration of AAPI Heritage Month took place in 1977.

The theme for 2022 is “Advancing Leaders through Collaboration.” AAPIs have contributed to American society in the fields of science, medicine, literature, art, sports, government and law. To cite just a few examples, Kamala Harris is the first Asian American to become vice president of the United States and Jim Yong Kim served as the 12th president of the World Bank. Suni Lee, Nathan Chan and Chloe Kim are among many Asian American Olympic Gold medalists.

As this year’s AAPI Heritage Month comes to a close, take time to learn about, remember and celebrate the many valuable contributions to American society made by AAPI individuals and organizations. AAPI Heritage Month also brings the opportunity to stand in solidarity, speak out against the senseless murders and assaults against AAPI individuals, and fight hate crimes.

The month brings the opportunity to raise our voices to turn the wave of racism and hate crimes toward AAPIs. An attack on an AAPI individual or community is an attack on America. Rather than living in fear, racism and hatred, we need to learn to live in love, peace and kindness and work toward embracing the other. We can do this not only during AAPI Heritage Month, but every month.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 21 books, most recently Spirit Life, Invisible, Reimagining Spirit and Intersectional Theology co-written with Susan M. Shaw. She is the host of Madang podcast on Christian Century.

Related articles:

Why I wrote a book about Asian Americans being invisible | Opinion by Grace Ji-Sun Kim

Cultural divides: ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ and my experience as an Asian American Christian | Opinion by Shauw Chin Capps

On the anniversary of the Atlanta shootings, a call for empathy, intimacy and holistic racial reconciliation | Opinion by Amanda Clark