No one should be surprised. These divisive times we currently endure remain strikingly similar to this nation’s very beginnings. Yes, the current administration continues to break norms and in now predictably unpredictable fashion. It provokes disdain, sows discord, stokes anger and intentionally creates division. Yet we all bear significant responsibility for these divisions and for this high degree of angst. We also have some hope from our past.

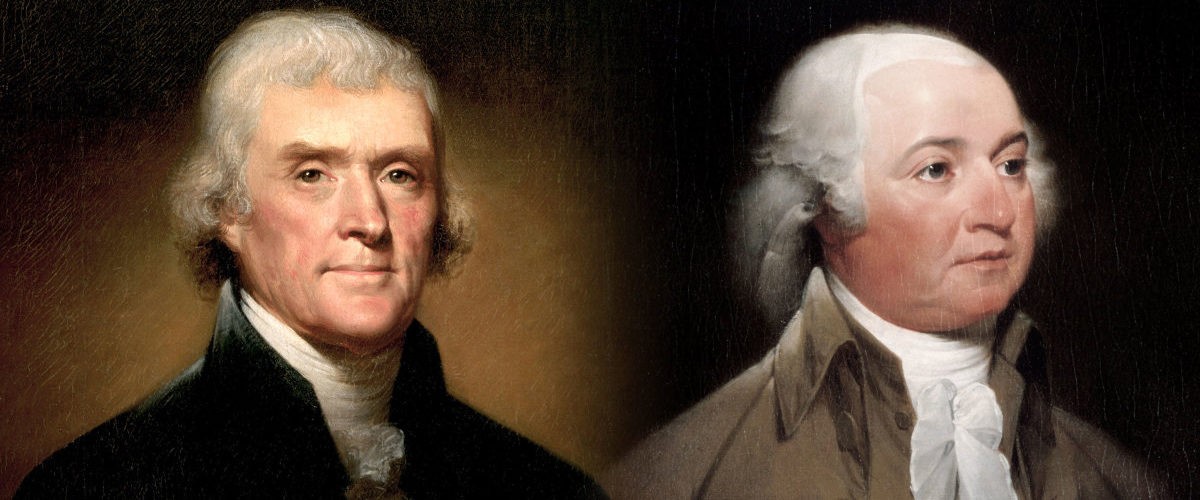

The founders of this republic planned for, even participated in, similar discordant behavior. The troubled relationship between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson serves as a case in point.

John Adams, a common man of Puritan, New England Yankee heritage, remained keenly aware of his insufficiencies. Yet his passion for learning and his contagiously eager desire to exceed expectations propelled him in the very best directions of patriotism. He embodied a lifelong commitment to the common good. He believed in and worked for a nation he imagined rising with efficient, professional government, public education, freedom of religion (including for Jewish immigrants), civil engagement and civic opportunities for as many as possible, and a strong navy to protect the coast. All this was to be funded by appropriate and equitably levied taxes.

John Adams, a common man of Puritan, New England Yankee heritage, remained keenly aware of his insufficiencies. Yet his passion for learning and his contagiously eager desire to exceed expectations propelled him in the very best directions of patriotism. He embodied a lifelong commitment to the common good. He believed in and worked for a nation he imagined rising with efficient, professional government, public education, freedom of religion (including for Jewish immigrants), civil engagement and civic opportunities for as many as possible, and a strong navy to protect the coast. All this was to be funded by appropriate and equitably levied taxes.

Thomas Jefferson, aristocratic, multilingual, exceptionally talented, calm, controversial and hypocritical, sadly embodied the many tense contradictions still rending our current social fabric. Committed to lifelong learning, visionary and expansive in his hopes for this nation, skilled in the art of diplomacy, intellectually curious, an early and ardent advocate for the separation of church and state, he remains perhaps the most influential politician ever to hold sway in our nation’s capital.

Thomas Jefferson, aristocratic, multilingual, exceptionally talented, calm, controversial and hypocritical, sadly embodied the many tense contradictions still rending our current social fabric. Committed to lifelong learning, visionary and expansive in his hopes for this nation, skilled in the art of diplomacy, intellectually curious, an early and ardent advocate for the separation of church and state, he remains perhaps the most influential politician ever to hold sway in our nation’s capital.

Unlike Adams, Jefferson never could bring himself to condemn slavery. He knew it was wrong. But it was not because he thought the Africans he enslaved were his equal. He did not. He likely saw his investment in human capital as a losing proposition for the long run.

In other words, he knew slavery was an albatross, a great, weighty guilt infecting the psyche of the young nation. Yet again, unlike Adams, he could never bring himself to work for its abolition. Instead, tragically, he never emancipated the people he enslaved. Not even Sally Hemmings, likely the mother of at least four of his children.

For Jefferson, knowing the wrong of something so interwoven into his lifestyle made curtailing it highly inconvenient. Slavery served as the very basis for his plantation economy. His many interests, skills and daily tasks were facilitated by free labor. He bought the best books (which became the foundation for our current Library of Congress), collected the finest wine, cultivated the most interesting exotic plants, played the violin, experimented with architectural designs, collected the finest art and could converse in six languages (English, French, Spanish, Italian, Greek and Latin). He ranks highly as a Renaissance man. Except we now realize this: a virtual army of workers facilitated his every move and catered to his every whim.

Our nation’s structural demons continue to haunt much of our public and private interactions because we have benefited widely and unjustly from a tragic inheritance. Much of our nation’s early infrastructure was constructed on the backs of unpaid labor. Like Jefferson, curtailing the economic benefits associated with either free labor or today’s low-paying jobs for migrant workers, or unsafe plant or factory jobs appears economically self-defeating. While it feels like the right thing to do morally and ethically, the pull of our pocketbooks too often overwhelms the better angels of our nature. Such was Jefferson’s dilemma.

“Our nation’s structural demons continue to haunt much of our public and private interactions because we have benefited widely and unjustly from a tragic inheritance.”

So when our current president lambasts any effort to remind our nation and to teach our children that we are not perfect, he is not the first. And while we do indeed have so much to be thankful for, our history is also sadly replete with bigotry, racism, sexism and tragic spasms of violence against those deemed insufficiently American.

With Jefferson, we continue to struggle with the long shadows of structural and systemic racism. We cannot seem to fully admit to or redemptively work through these historic tragedies.

And yet, thankfully, we also have the legacies of those like John Adams, who adamantly attempted to strive for a higher moral ground and to call upon his country to do likewise. He and many other women and men like him recognize the considerable, even incalculable, gifts this land offers.

Adams simultaneously provided the courageous, necessary critique of his own behavior and the behavior of his contemporaries. Our current time requires the same honesty. A confessional perspective is vital. A brave determination to address our historical insufficiencies is essential. Mending our torn and tattered social fabric is necessary. And finding respect for those we are tempted to despise is imperative.

Through their shared letters, we have ample evidence that Adams and Jefferson, harshly opposed to one another in their middle years, grew into intimate and consoling friends as they aged. Adams remained disappointed that Jefferson never could fully condemn the institution of slavery. But he grew to love the man. And that love was fully reciprocated. Let us work and pray for a similar grace.

David Jordan serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Decatur, Ga.