As a political ideology, Christian nationalism is not the traditionally conservative movement its adherents claim it to be, U.S. Rep. Morgan McGarvey said during a panel discussion on saving democracy hosted by Crescent Hill Baptist Church in Louisville last Saturday.

Morgan McGarvey

Morgan was one of six panelists in the “Defending Democracy” conversation moderated by Mark Wingfield, executive director of Baptist News Global. The event followed a lecture on Christian nationalism’s threat to democracy by David Gushee, professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology and a BNG columnist. BNG was a sponsor of the event and livestreamed both the lecture and the panel discussion on its Facebook page.

Conservatism as default position

Wingfield opened the discussion by asking how conservatism became understood by some as the correct or default political position while the left is viewed as out of touch with the faith.

Morgan, a Democrat and an active Presbyterian, said that question must be viewed through the rise of Christian nationalism, a movement that values theocracy over the “don’t tax, don’t spend” philosophy of traditional conservatism.

“The Christian nationalists are … fiscally liberal and socially conservative.”

“The Christian nationalists are the exact opposite,” he said. “They are fiscally liberal and socially conservative. They will spend every red-hot cent they can get their hands on to enact their agenda, which is hostile to democracy. So, when we talk about which way they are steering, it’s not just how they are steering to the right, it’s how they’re steering away from what I would call the traditional right and what impact that has on politics.”

Christian nationalism is better described as an anti-democratic political ideology driven by the belief the nation should be governed by Bible-based laws, he said. “It is exclusive. It is getting rid of equality. It is hostile to the ideas of democracy.”

Cassie Chambers Armstrong

Democratic State Sen. Cassie Chambers Armstrong said she has witnessed the growth of that ideology in Kentucky’s statehouse, where protections for religious freedom and the line separating church and state are being continually challenged.

“That began to be eroded and chipped away over time. And every day in the General Assembly I see how state legislators are stepping in to push that boundary even further, and every time there’s a crack to keep pushing and pushing and pushing,” said Chambers Armstrong, also an assistant professor of law at the University of Louisville.

Gushee added that the portrayal of the right as politically and morally correct also results from “an aggrieved, traditionalist Christian conservative population that has bought the narrative that the country has drifted to the left or has been pulled headlong to the left by the woke liberals, and that it needs to be wrestled back to the right — which they understand indeed to be the default position.”

“There are no boundaries on the right.”

“The mindset is almost like you could never be too far right,” he added. “There are no boundaries on the right. If you want to remake America’s church-state arrangements, that’s fine because anything that takes you to the right is good. Anything that takes you to the left is bad. And that is a very dangerous place to be.”

Are liberals really devoid of faith?

Wingfield asked panelists to explain the notion that conservatives have a monopoly on religion while liberals are devoid of faith.

Sam Marcosson

Those on the left can take a small part of the blame for that development because they failed to recognize the centrality of faith for religious conservatives and to engage their concerns about the moral drift of the nation, said Samuel Marcosson, professor of law at the University of Louisville’s Louis D. Brandeis School of Law.

“I think there could have been ways — and maybe there still are — to speak to those concerns in a way that is sympathetic to the concerns while trying to not give into the baser impulses, the bigotry, the intolerance,” he explained. “And sometimes people want to feel heard and respected in the concerns that animate their lives, the faith that, for some people, is a matter of good faith and not just hatred and not just animus.”

Chambers Armstrong said she has been asked how she can be a Democrat and a Christian at the same time. Her response: “There’s space in our debate to point out the way that some of the policies that are being championed by the new extreme right really aren’t rooted in Christianity or Christian values.”

“Policies that are being championed by the new extreme right really aren’t rooted in Christianity or Christian values.”

Those include laws criminalizing homelessness and jailing people for sleeping on the streets, she said. “That is not what my faith teaches me about how we are to treat people who are struggling in our community. That’s not what I teach my children about how to treat people who are struggling in our community.”

But being asked the question is also a teaching moment, she added. “One thing I try to do is to authentically, when it is called for in the moment, talk about my faith values and talk about my understanding of my religion.”

Phillip Shepherd

Getting those points across will require Americans on the left to become more comfortable speaking about the language and symbols of faith, said Kentucky Circuit Judge Phillip Shepherd.

“The people on the right in our political world have expropriated the symbols of faith and family and patriotism, and people on the left have been generally uncomfortable about talking about those things and about claiming the symbols that are important to so many people in their daily lives,” he explained.

Erica Whitaker

But it’s also important to discern the white supremacist propaganda encoded in some religious symbols, including white Jesus, said Erica Whitaker, associate director of the Institute for Black Studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky and a BNG board member and columnist.

“This is challenging for our society because when a society that oftentimes leans into Christian nationalism that then upholds a patriarchal system, that symbol represents God, who is then mirrored in the image of a white male body. This becomes very challenging even for liberals, even in the African American communities that are oftentimes rooted in patriarchal in white theology.”

Public education

Christian nationalism also drives the attacks on public education, Wingfield said. He cited a radio interview he heard last week with a woman who favored school vouchers in order use taxpayer money to religiously “indoctrinate” her children.

“Many of us would say that this Christian nationalism movement and those adjacent to it are not concerned about the common good,” he said. “They’re concerned about their own good, what’s best for them, not what’s best for my neighbor.”

The erosion of church-state separation took a big leap forward in 2023 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District that a high school football coach’s on-the-field prayer gatherings constituted private speech and therefore protected, Chambers Armstrong said.

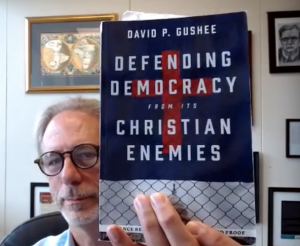

David Gushee holds up a copy of his new book.

“The question was, would a reasonable observer watching this conclude that the government had endorsed the religious beliefs or the religious expression? And I think most people looking at something like that would probably say, ‘Yes, that looks like the government is endorsing that religious expression.’”

Bills requiring Ten Commandments displays and Bible teaching in public schools are equally threatening to students’ constitutional freedoms, she added. “Our schools are especially important because they’re the way we give people a path to participating in that democracy, they’re the way we create futures for folks. It’s particularly important that to our children we are saying, it doesn’t matter if you have whatever faith or no faith at all, you are still entitled to all of the fruits of our democracy and to participate fully.”

“I must be just as concerned about that kid who is the only one in the class who does not share the majority Christian view as I would be about my own child.”

Gushee recommended using the “language of covenant” to reach understanding with everyone in a community, including conservative Christians and people of other faiths or no faith. “I must be just as concerned about that kid who is the only one in the class who does not share the majority Christian view as I would be about my own child.”

But McGarvey said the racism inherent in Christian nationalism and its campaign against public education should not be overlooked.

“When you talk about schools, in particular here in Louisville, we very much see that playing out even with a ballot initiative up this November that would direct public dollars toward religious institutions,” he said. “And what I see from a lot of the Christian nationalists in particular is that their idea of covenant is we are right and you are wrong, and therefore we are going to do what’s right.”

Is there hope?

In a concluding question, Wingfield asked the panel where they find hope, given the challenges of gerrymandering, the Electoral College and the lack of term limits for the Supreme Court.

Marcosson agreed all those challenges are real and unlikely to be changed legally. That’s his “doom and gloom” perspective as a law professor, he said.

“Here’s the more hopeful voice and that’s the voice of a gay man. The year I graduated from law school … 1986 was the year the Supreme Court decided Bowers against Hardwick upholding the constitutionality of laws criminalizing sodomy between people of the same sex. … Almost as soon as I graduated, that decision came down and I was crestfallen. I thought all of these values that I thought I was taught in law school, that I believed in the court being a tool for progressive change, that I was not included in that. I was not included in the idea of equality, liberty, privacy and it made me very cynical for a while and it was very difficult to get over that.

“In my lifetime, that same Supreme Court overturned Bowers against Hardwick less than two decades later in Lawrence against Texas and just 15 years later, less actually, they decided Obergefell, recognizing the equality and liberty of same-sex couples to marry. So change is possible. It takes time.

“It can restore cynicism or turn cynicism into faith, so we don’t have to give up just because things may look dark right now and the light may not seem to be coming on anytime soon. The lesson of that experience is look ahead to times that might be better.”

See David Gushee’s lecture on democracy here.

See the panel discussion here.