Black Christians engaged in the struggle for racial justice must not turn a blind eye to the oppression in church and culture of gays and lesbians, women and Latinx, Asian and Native Americans, author and scholar Marvin A. McMickle said during a virtual discussion hosted by New Baptist Covenant.

The need to empathize with other rights movements became clear as LGBTQ, female and other students repeatedly said “me too” when studying the plight of African Americans, said McMickle, who directs the doctor of ministry program and is a religious studies professor at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School in New York.

These encounters convinced him that caring only about the discrimination faced by Blacks actually undermines the movement.

“Our job is to listen to the people who are saying to us, ‘me too,’ and dislodge ourselves from our own preoccupations, our own complaints, our own litany of woes long enough to hear, empathize with and act on the woes and concerns of others,” he told Aidsand Wright-Riggins, NBC executive director and moderator of the Zoom event. “I think we have to listen to these ‘me too’ voices.”

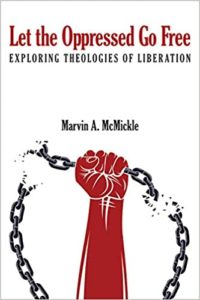

The framework for the hour-long conversation was McMickle’s new book, Let the Oppressed Go Free: Exploring the Theologies of Liberation, in which he addresses issues including race, poverty, womanist theology, gay rights, Black and Native American rights and other causes.

The framework for the hour-long conversation was McMickle’s new book, Let the Oppressed Go Free: Exploring the Theologies of Liberation, in which he addresses issues including race, poverty, womanist theology, gay rights, Black and Native American rights and other causes.

“What the book is designed to do is to introduce people to whatever form of oppression they may not personally be experiencing and urge them to be sympathetic,” he said.

McMickle also drew on 40 years in pastoral ministry during the online discussion to offer practical suggestions on how and when people of faith, and especially pastors, can connect Scripture and the challenges of everyday ministry to Black liberation theology and other faith-inspired justice movements.

The idea in the book emerged from being asked, often in classroom settings, why his understanding of oppression seemed limited to African Americans.

“What they said was, ‘You’ve got a story of oppression that is rooted in your race or ethnicity and I’ve got a story of oppression that is rooted in my economic class or rooted in my gender or rooted in my sexual orientation,’” he explained. “We’re all in this together. We need to get to a place where our oppression is not the only oppression that matters.”

Aidsand Wright-Riggins

Wright-Riggins asked how readers of his book might broach topics like women in ministry and LGBTQ inclusion into congregations and denominations that do not embrace those views.

McMickle said his own acceptance of the ordination of women came easy because his first pastor growing up was female.

“When I got to Union (Theological Seminary) in the 1970s was the first time I heard a conversation among Black males about why women were even enrolled in the seminary and why they wanted to be in the ministry,” he said. “I couldn’t even comprehend that.”

Accepting Christians who are LGBTQ was more difficult initially because of his tough upbringing on the southside of Chicago where homosexuality was viewed with hostility.

His own acceptance of the ordination of women came easy because his first pastor growing up was female.

But encountering gay and lesbian students in academic settings launched him onto “a listening experience and a learning experience where I had to square what I had been conditioned to think versus these real people I liked and admired … and you hear them say they have been called to ministry just like you.”

That is where McMickle said he began to fully see the hypocrisy in the way the Bible is used to oppress LGBTQ people, women and others.

He cited Romans 1, in which God is said to give men over to lust for other men, and women for women. “OK, I can’t take it out. But Paul then goes on to say he also gave them over to murder, envy, greed, jealousy and division. My question is: When is the last time you preached on any of those with the same ferocity (as lust)?”

He noted similar examples with verses from Deuteronomy and 1 Corinthians. “We pick the ones who we want to hate, we excuse the ones we want to excuse. I think we have to listen to these ‘me too’ voices making a legitimate case for their inclusion.”

The motivation for inclusion also can be found in the Bible, he said, explaining that scriptural principles such as treating others “as we want to be treated,” love of neighbor and remembering God as the maker of all persons should drive the treatment of those typically downtrodden in society and in the church.

McMickle said his advice to pastors is to preach on these topics in a balanced manner that allows time also to cover matters of personal piety, spiritual formation, grief and the running of the institutional church.

“We don’t need you to be Amos, Micah or Jeremiah every week. We just need you to be Amos or Micah or Jeremiah when the moment is right.”

“I say it in all my books: Do not try to be Amos or Micah or Jeremiah every week. We don’t need you to be Amos, Micah or Jeremiah every week,” he said. “We just need you to be Amos or Micah or Jeremiah when the moment is right. What I tried to do over the course of my almost 40 years in pastoral ministry was to keep that rotation in mind and capitalize on current events that would allow me to then draw on liberation theology as a point of reference.”

Those current events are all too tragically plentiful, McMickle said. Incident after incident of police brutality occurs at an astonishing pace, making it just as dangerous as ever to be Black in America.

“I am really out of words to understand this, and I think America is running out of interest,” he lamented. “And until we take every death as if it impacted us directly … it’ll keep happening.”

This all adds up to giving preachers a lot to preach about, he concluded. “Now, if you can’t do liberation theology in this current climate, then the Lord did not call you to preach.”