I sat in bed staring at my laptop, the dozens of Google tabs detailing the journey I’d been on. Books were buried in my comforter, creating a type of literary war zone.

My ojeras (the bags under my eyes) decorated my face the color of day-old bruises. I kept opening the folder on my phone titled “Do Not Open,” robotically scrolling through each social media app to distract myself from the sharp, sucker-punch pain in my gut that had lingered for days.

It wasn’t the first time I had felt the pangs that come when the past reveals itself to you, when an unknown history digs itself up from the grave. Colonizer or colonized, oppressor or oppressed — there’s a moment after the deep, dark, often lonely work of becoming our own archaeologists that the pangs hit. It’s a surprising pain that often comes when we dig up the skeletons from the ground, when we realize the dirt we stand on is tainted and the reality we’ve been fed is curated.

“It’s a surprising pain that often comes when we dig up the skeletons from the ground, when we realize the dirt we stand on is tainted and the reality we’ve been fed is curated.”

While this wasn’t the first time reality hit, it would be the first time it pulled a fast one on me while I was writing an academic paper — a process, I was told, that was supposed to be “objective,” a discipline solely of the mind. Up until this point, no one had warned me this would happen, that the work would feel this personal.

The dominating culture taught me to separate myself from what I study and, consequently, to live with a fragmented identity. But when our musings about life and faith exist only in fragments, we live disembodied realities. God becomes disembodied too.

It’s easier when we’re fed what to think, what to believe about ourselves, our histories, and God. When our identities are programmed, we’re not taught to really engage or to bring our whole selves to the table. We’re taught our own thoughts and hearts cannot be trusted in any way, and thus we live in shame, a widened chasm.

But something painful and terribly beautiful happens when that chasm begins to narrow. I think this narrowing, this shrinking space where theology, history and our identities — hearts, minds, bodies and souls — begin to blend together, is where the pangs are felt most sharply.

It may not feel like it in the moment, but this is also part of the journey toward liberation.

That day while in bed with my laptop and books open, that chasm narrowed again. Reality paid a painful visit. And it didn’t come alone. It brought grief along with it — that deep, gut-wrenching sense of grief. It was a sorrow from a time deep in the past, before I even existed — a grief that my antepasados, my ancestors, knew, one that hovered above time, spanning history.

“What do you do with generational grief? I sat in it for a while. And then I got to work.”

What do you do with generational grief? I sat in it for a while. And then I got to work.

Initially I called the angst I felt that day “research grief”; it’s the grief that comes when getting deep into the thick of researching difficult topics. Surprisingly, this is a common thing in the academic world. I once heard of a woman who began losing sleep, her hair and her sanity during her time as a doctoral student writing her dissertation on the Holocaust. Even trying to make sense of other people’s trauma can traumatize.

This notable pang of research grief surfaced early in my seminary career during a Women in Church History and Theology class. Although I was several courses into my master of divinity program, I was new to exploring the topics of women and people of color as they pertain to theology. The dominating culture had yet to invite me to see myself and my culture within God’s story.

But I thank Creator for my stubbornness, for my combative spirit, which the dominating culture has deemed too much — muy fresca.

When I began this course, I was attending my second seminary. I had left the first one only months prior, after tussling with professors and pastors and experiencing firsthand the demons of sexism and racism. I admit, being raised in an immigrant Roman Catholic community and then transitioning to Protestantism as an adult left me unfamiliar with the ins and outs of evangelicalism. Not only was I blissfully ignorant of what I was stepping into spiritually, but as a Cuban American born and raised in a city predominantly made up of Cuban Americans, I had yet to wrestle with my cultural identity in a majority, non-Hispanic white context.

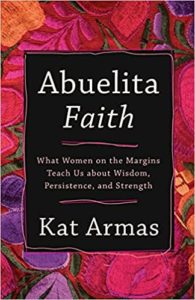

This column is excerpted from the new book Abuelita Faith by Kat Armas and is used by permission of Baker Publishing, ©2021. Kat Armas, a graduate of Fuller Theological Seminary, is a Cuban-American writer and speaker. She hosts The Protagonistas podcast, where she highlights stories of everyday women of color, including writers, pastors, church leaders and theologians. She also works on the Living a Better Story project at the Fuller Youth Institute and speaks regularly at conferences on race and justice.

This column is excerpted from the new book Abuelita Faith by Kat Armas and is used by permission of Baker Publishing, ©2021. Kat Armas, a graduate of Fuller Theological Seminary, is a Cuban-American writer and speaker. She hosts The Protagonistas podcast, where she highlights stories of everyday women of color, including writers, pastors, church leaders and theologians. She also works on the Living a Better Story project at the Fuller Youth Institute and speaks regularly at conferences on race and justice.

Related articles:

All Saints Day and every day: the ‘dangerous, restless speech’ and revolutionary act of lament | Opinion by Laura Mayo

The Tulsa Race Massacre is personal to me, and remembering is a holy act | Opinion by Aidsand Wright-Riggins

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard