It was my last conversation with, let’s say, Tim, a close friend for six decades. Our stockpile of trust built a sturdy container strong enough to hold honest end-of-life conversations. Tim is dying and he knows it. Each telephone conversation I approach with fear and trembling, but once into it I feel profound privilege.

At this last one we both were feeling its finality. He announces up front, “I can handle only a few minutes.” Then comes the question, “Mahan, you have conducted a lot of funerals over the years. What did you say?”

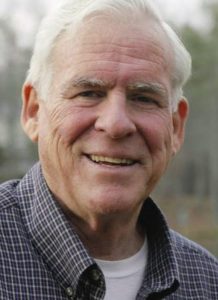

Mahan Siler

My stomach churns, mouth turns dry, both of us feeling the import of the moment. No time for explanation. Only distillation now. After a deep, deep breath, I break the silence, “Tim, I think I said only one thing. The differences were variations on one theme.”

“Well, what was it?” he pressed.

“Love never ends,” I said.

A long pause, then his words, “Maybe so. … Maybe so.”

Tim’s last words to me, “Maybe so.” I felt in them his integrity with a mixture of caution and a sliver of hope.

Years later, now more than five years ago, our son, Marshall, died by suicide at 54 years of age. Marshall is not a parishioner, nor a close friend. Marshall is our son. My son. What I said to Tim and his response to me felt incomplete.

“I’m reaching for more than ‘maybe so.’”

I’m reaching for more than “maybe so.” Could there be more? Does “love never ends” include an ongoing relationship with Marshall? Does the fuller version from the Apostle Paul that nothing in life or death can separate us from the love of God mean a continuing connection with Marshall?

I set out on a journey of exploration.

Before we continue with my journey, let’s name the resistance, likely in both of us, writer and reader. In our culture we are marinated in a materialistic worldview. The conditioning is deep in us all. Reality is only what can be observed, tested and measured. Life, according to this paradigm, is from birth to death. That’s it. It’s all we have. Ancestors are revered, but any ongoing relationship with our ancestors is absurd, only wishful thinking.

Even our language limits reality to our five senses. We speak of “making sense,” or “nonsense” or “immaterial.” Accordingly, a loving relationship beyond death does not “make sense,” in fact, is “nonsense” and “immaterial,” that is, impossible.

In addition, for those of us who identify as Christian, there is another layer of resistance. Many of us reel from the impact of manipulative pie-in-the-sky preaching. To be saved means an assured place in heaven. Subsequently, the abuse of the earth and the injustices that abound are distractions. Perhaps, in reaction, the Christians in my “tribe” seldom mention life beyond death and even less the prospect of a continuing relationship beyond death. I’m swimming against this stream.

Now, with these counter currents in mind, let’s continue the exploration.

When I was an active pastor, after a few weeks into the grieving, I would routinely ask, “Have you experienced your loved one in some way?” About half of the time the response was “yes.” I would hear what had not likely been shared with others — a sense of that person’s presence, a whisper, a dream, an apparition.

I’m remembering my pastoral visit to Hattie in her last moments. Standing by the hospital bed, I witnessed a remarkable surprise. In the midst of her struggle for last words she suddenly brightened with a glow on her face, looked beyond me, clearly responding to an invisible presence. She then relaxed into her last breath. I left pondering what had happened. In her shift to joy was she experiencing a welcome by someone, perhaps loved ones?

When Marshall died, I listened for any experiences that family and friends might be having with Marshall. While curious, I also was cautious. This is an uncomfortable question to raise. One granddaughter spoke to me privately of a couple of felt visitations from Marshall. She reported Marshall is lamenting the pain he is causing the family. That fits. He would be. Another person felt his playfulness, his teasing, a reminder of how they were together. These conversations whetted my appetite for a personal experience of my own.

“It happened. The gift came in a dream a couple of weeks after Marshall’s death.”

It happened. The gift came in a dream a couple of weeks after Marshall’s death. Early that morning, before sunrise, I experienced Marshall. The dream was in technicolor, a first for me. I don’t recall such a vivid, compelling dream.

In the dream Marshall is standing at the head of a table around which I sensed our family. But only Marshall is visible, a frontal view, up close and intimate. He radiates well-being. Cheeks with color, soft eyes, engaging smile, all of him exuding health in contrast to those stressful last months with his inner light flickering and outer life contracting. In the dream he extends his arms toward us with an inviting gesture, saying, “Let’s give thanks.”

I awake stunned, quick to my study, recording the dream before it faded. Then, once giving words to it, I sit back basking in this gift.

Is this not a visitation? I experienced him, his life energy. I felt him saying to us, “Look at me. See how well I am.” In his words, “Let’s give thanks,” I experienced him leading us, inviting us to move onward with gratitude. This too I noted. He was addressing the family with “let us be thankful.” As family gifts for the next Christmas, I made clay platters with Marshall’s invitation curved on the front and the story of the dream taped on the back.

This dream accompanied another surprise.

A few days after Marshall’s death, a neighbor shocked us with his creation. He didn’t know us; we didn’t know him. A chainsaw sculptor by trade, he decided to transform the six-foot trunk of a tree that had been protruding toward our main road for many years. He carved a dynamic deer, leaping from its hind feet soaring upward to new heights. His comment: “Usually I carve bears. This was a deer.”

This sculpture, alive and dynamic to my eyes, has become for me an icon. An icon, more prominent in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, is a portal through which one contemplates a sacred person or scene, Jesus in most instances. During these five years, three or four times a week, I make the pilgrimage to this leaping deer.

“Some who grieve frequently return to the graveside. I return to this icon.”

Some who grieve frequently return to the graveside. I return to this icon. It has become an opening into our relationship. Can it be, as it often seems, a sharing of energy with him leaping forward in the soul work before him and my leaping forward in the soul work before me?

My exploration includes an intellectual review of the extensive, existing research on the phenomena of Near-Death Experiences and nonlocal consciousness. Also, I am taking a fresh look at the death and resurrection of Jesus. The church declares with confidence: The love of God so vivid in Jesus is stronger than death. For his disciples, then and now, this means an ongoing, empowering relationship with Jesus.

I’m suggesting, does not this experience of “love never ends” include the grace of continuous relationships with loved ones, like Marshall? Perhaps it’s time for us to sit at the feet of ancestors, including indigenous ancestors, who assumed the presence and guidance available to them from those who have passed beyond this realm.

In this writing, I’m highlighting two sustaining practices: “Let’s give thanks” and my frequent pilgrimages to the icon. Both practices unite my energies with Marshall’s in our shared transformation of becoming more fully the Love available as our essence.

My purpose in these words is not to be persuasive or conclusive. Simply, I am bearing witness. I am a steward of this great surprise of recent years. Within the Mystery we wager with our life. We all do. This witness is a wager of my heart, more than mind.

The “maybe so” of Tim now lives in me as “it is so.”

Mahan Siler lives in Asheville, N.C. He is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He was one of the founders of the Alliance of Baptists and served two congregations as pastor, Ravensworth Baptist Church in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh, N.C. He also has worked in pastoral care in the health care setting.

Related articles:

Gifts of hospitality in the midst of grief | Opinion by Sara Robb-Scott

Grieving for those who still are here | Opinion by Barry Howard

When the dying stops, will we remember to address the multiplied grief of COVID?