Churches have come up with some creative ways to stay in their buildings in an era of plummeting membership and revenue.

But many others – estimates range from 4,000 to 7,000 a year – are just plain going out of business on an annual basis.

Some of the causes are well known — rising secularism, generational rejection of institutions and changing concepts of what constitutes giving. A lot of Christians simply don’t feel they need to attend worship to be faithful believers.

But another factor that can lead to extinction is an emotional attachment to facilities so strong as to cripple a congregation’s willingness to share the gospel and make disciples.

Churches in those situations often must hit financial and attendance bottoms so severe that selling the sanctuary becomes an acceptable idea, said Mark Teasdale, associate professor of evangelism at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois.

Mark Teasdale

“It’s either that or don’t exist,” said Teasdale, author of Go! How to Become a Great Commission Church, and Evangelism for Non-Evangelists: Sharing the Gospel Authentically.

Teasdale said his teaching and writing on the over-attachment buildings has been inspired by witnessing seminarians-turned-pastors arriving at churches crippled with property related debt.

Shouldering crushing mortgages and unable to finance repairs, these struggling congregations barely have time for any activity related to evangelism.

“They can’t engage in any serious missional outreach as long as they carry this albatross of a building,” he said. “That mortgage is hampering them from doing almost anything.”

Teasdale noted a recent Barna survey as an example.

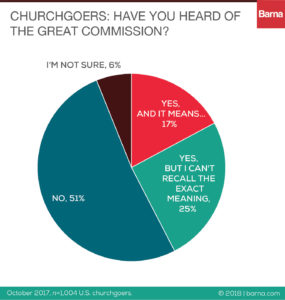

The March 2018 study reported that 51 percent of churchgoers don’t know what the Great Commission is.

Another 25 percent said they had heard the term but didn’t know its meaning. Only 17 percent could identify its meaning, according to the study Barna conducted with Seed Company.

Despite being able to devote so little energy to educating new and existing Christians about such things, Teasdale said, failing congregations engage in strategies to keep their facilities.

A common approach is to deed property to larger, thriving churches. The smaller group retains access to facilities that become satellites of the bigger fellowships, he said. Often, that option is selected by congregations who desire for their identity to be connected to mission.

“They recognize that the emotional capital they had invested in the building needs to be invested in participating in God’s work of making disciples,” he said.

Rather than losing their identity, those churches reclaim it by selling assets to free up financial and volunteer time.

But it’s more often the case that desperation drives a church to take bold action.

“At this point your primary emotion has become fear,” Teasdale said.

Members become convinced they are going to die as a congregation if they don’t make hard decisions, he said.

“They know they have do something and go to extreme lengths,” he said. “Their motivation may not be missional disciple making, but they may say ‘we can put the building on the table.’”

And there also are those who lose everything because they cannot let go, Teasdale said. He refers to that option as “exile,” since the congregation winds up being dispersed among other fellowships.

“Some congregations have closed because they failed to be involved in the mission of the church,” Teasdale said. “In those cases, they become emotionally bitter.”