Four churches were expelled from the Southern Baptist Convention Feb. 23 in a joint action that gave the appearance of equating LGBTQ inclusion with predatory sexual behavior.

Among the four churches expelled, two were removed due to welcoming LGBTQ Christians into fellowship and two were expelled for reportedly employing known clergy sex offenders.

The SBC Executive Committee, meeting in Nashville Feb. 23, debated the expulsions in a closed session. The outcome later was reported in an open session and cited by Baptist Press, which is part of the Executive Committee staff and structure.

The Nashville Tennessean published a Feb. 23 story with the headline “Southern Baptists expel two churches for sex abuse and two for affirming homosexuality.” That prompted one Nashville resident to call out a false equivalency via Twitter: “Why put them in the same headline? I understand they are both related to SBC issues, but being gay relates to DNA, whereas sexual abuse is a deliberate choice that causes lifelong harm to another human being. Tennessean: please work on your click bait tweets.”

The Nashville Tennessean published a Feb. 23 story with the headline “Southern Baptists expel two churches for sex abuse and two for affirming homosexuality.” That prompted one Nashville resident to call out a false equivalency via Twitter: “Why put them in the same headline? I understand they are both related to SBC issues, but being gay relates to DNA, whereas sexual abuse is a deliberate choice that causes lifelong harm to another human being. Tennessean: please work on your click bait tweets.”

Baptist Press took a more generic approach to its headline — “SBC Executive Committee disfellowships four churches” — even though the story’s lead lumped the two things together as “adverse policies and practices” that required expulsion. And that is, in fact, the reality of the mechanism in place to report offending SBC congregations due to sexual abuse, racism or LGBTQ inclusion; all complaints filter through the same online portal to the SBC’s Credentials Committee.

Jim Conrad

Jim Conrad, pastor of Towne View Baptist Church in Kennesaw, Ga., which was expelled Feb. 23 due to its welcoming stance toward LGBTQ Christians, noted the irony of the day’s combined actions.

“Somebody reported us to the Executive Committee sexual predator, gay-loving portal because they seem to treat all those the same,” he explained. “Then we got a letter saying we were under investigation.

“There’s no differentiation in the portal. It’s the exact same process,” he added, noting that Kentucky seminary president Al Mohler — a candidate for SBC president this summer — tweeted almost identical wording Feb. 23 applauding both types of expulsions. “They put us in the same category as racists and sexual predators,” Conrad lamented.

Mounting pressure inside SBC

The SBC has been under increasing public pressure to address both clergy sexual abuse and human sexuality, but from different wings of the convention. Two conservative subgroups within the SBC have made an agenda of claiming the convention has become too “woke” and is sliding into liberalism by not being harsh enough against LGBTQ acceptance and other social justice issues.

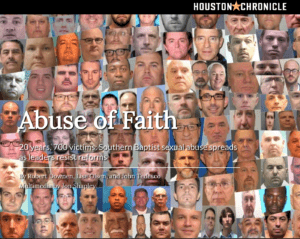

More traditionalist forces — and outside forces — have been highlighting the problem of clergy sexual misconduct. The Houston Chronicle two years ago published a series of articles detailing hundreds of cases of alleged abuse in SBC churches or by clergy or volunteers affiliated with SBC churches.

More traditionalist forces — and outside forces — have been highlighting the problem of clergy sexual misconduct. The Houston Chronicle two years ago published a series of articles detailing hundreds of cases of alleged abuse in SBC churches or by clergy or volunteers affiliated with SBC churches.

That prompted SBC President J.D. Greear in February 2019 to call for an investigation into specific allegations against 10 SBC congregations cited in the newspaper’s reporting.

“I am not calling for disfellowshipping any of these churches at this point, but these churches must be called upon to give assurance to the SBC that they have taken the necessary steps to correct their policies and procedures with regards to abuse and care for survivors,” Greear said at the time.

Greear’s comments led one Georgia church to fire its minister of music, who had been accused but not convicted of abusing a teenager decades earlier. The SBC annual meeting in June 2019 included an emphasis on understanding and responding to sexual abuse that happens at churches or with clergy.

Then in February 2020, the Executive Committee expelled a West Texas congregation for employing a registered sex offender as pastor. That was reported to be the first time the convention expelled a church for clergy sexual abuse. Previously, churches had only been disfellowshipped from the SBC in modern history over LGBTQ-related issues and racism.

Expulsions due to clergy sexual abuse

Details of the complete accusations against the two churches newly expelled over clergy sexual abuse allegations were not made known. However, Baptist Press reported that Antioch Baptist Church in Sevierville, Tenn., was removed for employing a pastor who pleaded guilty to two counts of statutory rape through oral sex with a 16-year-old congregant in 1994 and that West Side Baptist Church in Sharpsville, Pa., was removed for employing a pastor who was convicted in 1993 of aggravated criminal sexual assault of a child in Denton, Texas.

What consideration was given to the hundreds of other instances of clergy sexual abuse cited by the Houston Chronicle — some involving larger and more prominent congregations — was not revealed.

The SBC is in the process of amending its constitution to make toleration of sexual abuse a specific reason for a church to be removed from the convention. Because of Baptist autonomy, the convention itself has no power to revoke the ordination of a pastor or to prevent a church from calling a pastor. The only power the convention has is to remove an entire church from the convention.

The only power the convention has is to remove an entire church from the convention.

The proposed amendment on sexual abuse — scheduled to receive a required second reading this June — would add a section defining a “cooperating church” as one that “has not been determined by the Executive Committee to have evidenced indifference in addressing sexual abuse that targets minors and other vulnerable persons and in caring for persons who have suffered because of sexual abuse.”

Expulsions due to LGBTQ inclusion

In addition to Towne View Baptist Church in Georgia, the second church removed from fellowship with the SBC Feb. 23 is St. Matthews Baptist Church in Louisville, Ky.

Michael Payne, chair of the Administrative Council at St. Matthews Baptist Church, told the Louisville Courier-Journal the decision “was apparently based on our congregation’s November 2019 reaffirmation of SMBC’s long-standing policy that a belief in Jesus as personal Savior is the sole criterion for membership in our church.”

Stained glass window at St. Matthews Baptist Church telling the story of the previous church building burning to the ground in an arsonist’s fire and how the church was ignited in worldwide mission with the power of the Holy Spirit coming down from heaven as on the day of Pentecost.

He added: “Nothing in the Southern Baptist Convention’s decision changes St. Matthews Baptist Church’s deep commitment to carrying out what God calls us to do in our worship and spiritual growth, as well as in ministries to those in need and fellowship within our church family.”

St. Matthews had been removed from the Kentucky Baptist Convention in 2018 — before its affirmation of an inclusive membership policy — because of its affiliation with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, a group of more progressive churches formed in reaction to schism within the SBC. Although some CBF churches broke away entirely from the SBC, others, like St. Matthews, maintained dual affiliation with CBF and the SBC.

The Louisville congregation has a long history of participation in the SBC because of its geographical proximity to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the SBC’s oldest seminary. Prior to the seminary’s sharp rightward shift in the mid-1990s, a number of seminary faculty, staff and students were members at St. Matthews, as were staff of the Kentucky Baptist Convention.

Because of the size of its 1,200-seat sanctuary — one of the largest in the state — St. Matthews often hosted state convention and regional Baptist gatherings.

For many years of the SBC’s internal schism that began in 1979 and culminated in 2000, St. Matthews’ leadership attempted to chart a centrist course, appealing both to members disaffected by the SBC and to those still under the employ of the SBC. Other Baptist churches in Louisville became known much earlier for full inclusion of LGBTQ persons.

The church’s 2019 decision to reaffirm its existing membership policy came after a period of internal discussion about LGBTQ inclusion in the church in light of individuals and families wanting to participate in the congregation.

Mohler response

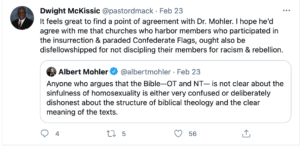

Mohler, president of nearby Southern Seminary, tweeted an indirect affirmation of the church’s expulsion Feb. 23: “Anyone who argues that the Bible — OT and NT — is not clear about the sinfulness of homosexuality is either very confused or deliberately dishonest about the structure of biblical theology and the clear meaning of the texts.”

That tweet created common ground with one of Mohler’s most frequent critics, Texas Baptist pastor Dwight McKissic, who has called for Mohler and Southern Seminary to do more to repent of the seminary’s racist roots.

That tweet created common ground with one of Mohler’s most frequent critics, Texas Baptist pastor Dwight McKissic, who has called for Mohler and Southern Seminary to do more to repent of the seminary’s racist roots.

“It feels great to find a point of agreement with Dr. Mohler,” McKissic tweeted.” I hope he’d agree with me that churches who harbor members who participated in the insurrection & paraded Confederate Flags, ought also (to) be disfellowshipped for not discipling their members for racism & rebellion.”

Demographic trends

The SBC’s hardline position on same-sex orientation runs headlong into the reality of cultural trends and American public opinion, but that is perceived as a badge of honor, not a barrier.

The day after the SBC expulsion action, Gallup reported that one in six Americans in Gen Z — those who are currently ages 18 to 23 — now identify somewhere within the LGBTQ community. And the percentage of Americans overall identifying somewhere within this community continues to grow — currently 5.6% of the population compared to 4.5% three years ago.

“One of the main reasons LGBT identification has been increasing over time is that younger generations are far more likely to consider themselves to be something other than heterosexual,” Gallup reported.

Southern Baptists — like all faith groups — spend much time and energy seeking to reach younger generations with the gospel message and to engage them in the life of the church. Yet views on human sexuality continue to put up barriers toward that goal — not only because younger adults are now more willing to express their sexual orientations but because the population at large has become more accepting of LGBTQ persons.

In a Feb. 22 address to members of the SBC Executive Committee, SBC President Greear urged the convention to be more open to discussions on race and racism but not on sexuality.

“The sanctity of life and marriage, the sinfulness of homosexuality — these are things that faithful Christians cannot disagree on.”

“I’m not talking about communicating ambiguity on things the Scriptures speak clearly on — the sanctity of life and marriage, the sinfulness of homosexuality — these are things that faithful Christians cannot disagree on and our consciences are captive in these to the word of God,” he said.

Towne View’s story

As with St. Matthews, the journey toward inclusion at Towne View Baptist Church in the northwestern suburbs of Atlanta began with a couple who wanted to join the church.

Towne View Baptist Church

Pastor Conrad acknowledges that his own understanding and theology of human sexuality was evolving when a young gay couple with three young children began attending.

Conrad was raised in “a very conservative” Southern Baptist environment in South Florida, where he was taught that same-sex attraction is a sin and no discussion was necessary about that. In more recent years, as he began “encountering people who are gay and claiming to be believers, I was scratching my head trying to figure out how that worked,” he recalled.

He also had read carefully a series of columns published in Associated Baptist Press (predecessor to Baptist News Global) written by Christian ethicist David Gushee. That 2014 series eventually became Gushee’s best-selling book Changing Our Mind.

“I was with him as far about the eighth column,” Conrad recalled. His traditional upbringing kept him from progressing as far as Gushee did in the series that documented the ethicist’s own real-time evolution on LGBTQ inclusion.

Then the Pulse nightclub shooting happened in Orlando, Fla., in June 2016. A gunman killed 49 people and injured 53 others at the popular gay club.

“Today is a terrible day for dads whose children were killed last night because they were gay.”

“That was a big event for me,” Conrad said. “It was the Saturday before Father’s Day. I remember stopping my Father’s Day sermon about 10 minutes short and saying, ‘Today is a terrible day for dads whose children were killed last night because they were gay.’”

Conrad’s growing conceptual understanding gave way to real life in May 2019, when a gay man visited Towne View. “He and his partner were moving to the area with a job, with their three boys they had adopted. They wanted to know if we could talk. He came back to church the next Sunday. It was the first time in my life somebody sat across from me and said, ‘Would I be welcome in your church?’”

Conrad realized he was looking at the very kind of prospect every pastor would love to have walk in the door: “An intact nuclear family with three children. It just so happened that in this family there were two dads.”

John and his partner, John, both had grown up in conservative Baptist churches, “knew Jesus and wanted their boys to grow up in church and have a gospel experience like they had,” Conrad said. “So I invited them to come worship with us and see how it worked out.”

The three boys began attending Sunday school, and the two men kept returning to church as well. Conrad told them: “If you sense the Spirit is leading you to this commitment, give me some time because this will take some work. … That led to us starting the process.”

Conrad realized he was looking at the very kind of prospect every pastor would love to have walk in the door: “An intact nuclear family with three children.

That summer Conrad “spent a lot of time reading,” especially Gushee’s book, the not-yet-published manuscript of another book about Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas, and Matthew Vines’ book about his journey through a Presbyterian faith to acceptance of himself as a gay man.

He began to involve the church’s deacons in the conversation. Eventually he informed the deacons he intended to recommend that the church adopt a statement that “anyone would be welcome as members of the church regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.”

That news set off secret meetings and parking lot conversations by members who opposed such an idea immediately. But ultimately the deacons by a strong majority approved just such a recommendation.

“As soon as word went out and I preached what we call ‘the sermon,’ about 30% of our folks left,” Conrad said. “I had hoped that after 25 years of pastoring in that church we could have at least had a conversation about it. The reality was that the folks who left didn’t show up for the conversation.”

The church approved the recommendation on inclusion by about a 70% affirmative vote.

“We lost 30% of our members and 40% of our money,” the pastor reported. “These were people who I had visited in the hospital, baptized, ordained. … They were people I considered friends.”

About a month after the congregational vote, John and John walked down the aisle of the church with their three boys between them. As the couple sought membership in the church that day, the congregation stood and applauded.

Soon another same-ex couple joined the church. And then, someone reported Towne View to the SBC.

“We weren’t going to fight it; we’re not going to fight,” Conrad said. “We knew when we took the action what would happen.”

Yet the church had determined not to leave either the SBC, the Georgia Baptist Convention or the local association in advance. “We were started 32 years ago as a mission church start by our local association. In many ways, we were the prototypical new church start in Southern Baptist life at that time.”

Because of this heritage, Conrad said, “either the SBC or the state convention or the association was going to have to tell us we’re not welcome.” Now that the SBC has taken its action, the church will voluntarily withdraw from the state convention and association.

“It’s a relief for us,” he said. “We can close this chapter and look forward to the next chapter.”

“Because we decided to welcome these people into our family, the denomination has said we’re no longer welcome in their family.”

And yet there is sorrow: “Because we decided to welcome these people into our family, the denomination has said we’re no longer welcome in their family.”

Social media post from a transgender woman who has found welcome at Towne View.

More recently, Towne View has welcomed a transgender worshiper who has transitioned from male to female before their eyes. “She came while transitioning, and then her first time in public as her new true self was to come to our church,” Conrad said. “We considered that such an honor that it was a tremendously humbling experience. Our folks have received her gladly.”

The SBC’s action against the small church has created a storm of media attention the pastor did not anticipate.

Speaking about 24 hours after the expulsion vote, he said: “The response we’ve had in the last two days has been absolutely overwhelming. I’m now fielding calls from the New York Times and Huffington Post.”

He’s also receiving calls from members of the LGBTQ community who want to tell their stories of rejection in the Baptist church — “intensely personal stories.”

“If we can offer hope to somebody that maybe there can be a place for them to have community …,” he said, “or if we can offer to other churches and ministers that there’s an example that this can be done … .”

He admits he used to get “frustrated when I heard pastors from ‘safe’ churches telling us what we should do. But God has been faithful. If we can offer that message beyond us, we’re glad to be able to do that.”

And an irony of the situation is that “our LGBT folks who have joined us are more conservative politically and socially than I would have imagined,” Conrad reported. “They are looking for a church where the authority of Scripture is paramount.

“I’ve had people say, ‘You don’t believe the Bible anymore.’ I say, ‘No we’ve done this because we believe the Bible.’”

Don’t expect to see Towne View hanging rainbow flags in the narthex or marching in parades, Conrad said. They are just planning to “be church” the way they’ve always been, but welcoming all Christians to worship and serve as they are called.