This weekend marked the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade, the court case that decriminalized abortion nationwide. But it was not the kind of anniversary celebration pro-choice advocates wanted to celebrate.

Opponents of abortion, however, celebrated the occasion with the same March for Life they’ve staged for decades — only with a celebratory tone and declarations about taking the fight to every state legislature.

After the court’s June decision, abortion was outlawed in many states automatically or through quick legislative action. Seven months later, states across the country continue to tighten their laws against abortion.

Jessica Valenti, feminist columnist and author, started the blog Abortion, Every Day after Roe was overturned, writing daily updates about abortion rights in America. In her blog from Jan. 20, she discussed the new stringent anti-abortion bill being pushed by Republicans in Arkansas and how its language could lead to the prosecution of pregnant women.

Vague language

The bill does not allow pregnant women to be prosecuted for “accidental miscarriages,” but they would be held liable if “wrongful death actions” take place, meaning the death of an unborn child was caused by a “wrongful act, neglect or default.”

This language is vague, and Valenti explained how such vaguery can be problematic for those who experience miscarriages: If the state determines a miscarriage was not accidental, for any arguable reason under this language, that person could be prosecuted for murder.

This refers to intentionally receiving abortion care, such as taking abortion pills to end a pregnancy. However, this language also threatens pregnant women who do not want to end their pregnancies but suffer miscarriages. As Valenti explains in her blog, many activities that are commonly done while pregnant could be used against them in a case evaluating the “accidental” nature of a miscarriage.

“A woman who was excited to be a mother but suffered a miscarriage could be prosecuted for murder by ‘neglect’ if she was believed to have knowingly lifted too heavy of an object.”

This means a woman who was excited to be a mother but suffered a miscarriage could be prosecuted for murder by “neglect” if she was believed to have knowingly lifted too heavy of an object. It could also mean a pregnant teenager who did not know to seek, or could not access, prenatal care could be held legally responsible by default if she had a miscarriage.

Among such bills in Arkansas and elsewhere, once-standard exceptions protecting access to abortion in cases of rape or incest, fatal birth defects or health risks for the pregnant woman are dwindling. The new laws are strictest in Idaho, North Dakota and Tennessee, where there are no exceptions allowed for any of these things.

Even so, doctors in other states warn the “nitty-gritty details” of their state legislation leaves little room for on-paper exceptions. This is because, under new abortion laws, doctors or patients must be able to prove an exception is necessary before providing abortion or miscarriage care.

But that is not always easy.

“Only about one-third of sexual assault victims report the crime to law enforcement.”

For example, in Mississippi, where there is an exception for rape or incest, the patient must provide proof of an assault from a police report. Only about one-third of sexual assault victims report the crime to law enforcement. The other two-thirds do not do so for various reasons, such as knowing an abuser closely and fearing retaliation once they find out the crime was reported.

There are also other obstacles, such as doctors needing to agree with legislators on what types of complications or birth defects warrant the use of abortive services.

For example, an abortion can only occur because of fetal abnormalities in Louisiana if the fetus has a diagnosis listed by the Louisiana Department of Health as “medically futile.” However, despite the list including 25 medical conditions, doctors have come across boundaries in providing care for pregnant patients who need abortions due to fatal defects not on the list, such as one woman who had to seek care in New York after being denied an abortion for a fetus without a skull.

Mail-order pills and the reality of abortion

In response to legislation seeking to criminalize abortion, more Americans are ordering abortion pills by mail because it is easier to obtain them this way and the distribution of the pills is harder to track. They also are starting to order pills to store in their medicine cabinets, just in case they need them in the future but cannot obtain them.

Reasons for ordering abortifacients online include the ability to access them in states where it is illegal, or the avoidance of medical staff who may judge their decision to take the medication. Obtaining the pills this way also helps pregnant women in states with vague laws avoid criminal charges, as they do not have to interact with anti-abortion nurses or doctors who they fear may report them to authorities.

And amid the discussion on what moral stance Americans should or should not take on the issue of abortion, the New York Times yesterday published an article including photos of what is removed from a person having an abortion during the early weeks of pregnancy. The photos were originally published last fall by The Guardian.

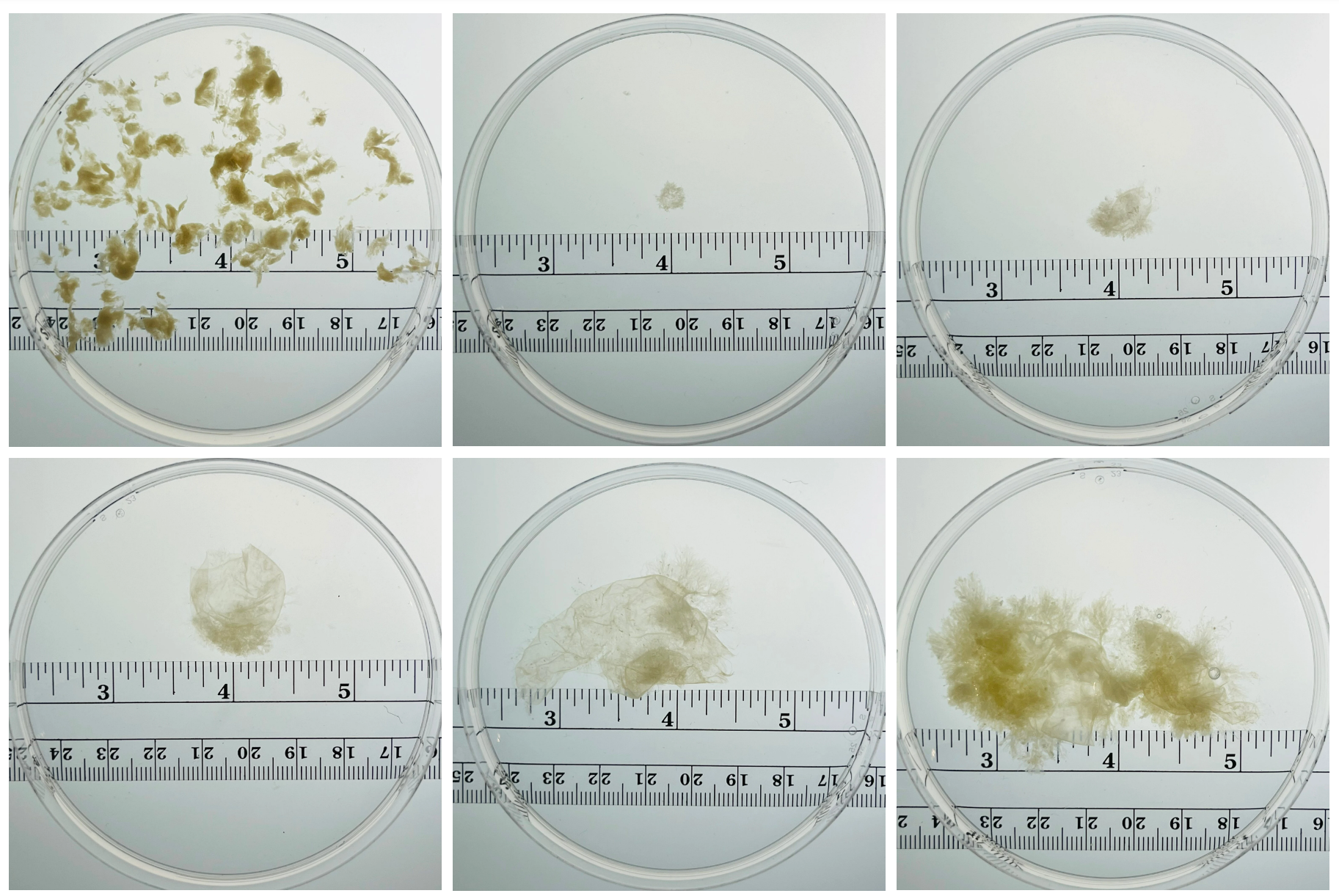

Depicting petri dishes, some with small fragments of uterine lining and others with gestational sacs, from weeks five through nine of pregnancy, the images went viral last fall, and are going viral once again. Viewers were shocked to see the minimal amount of tissue that remained on the petri dishes, and some believed they were altered before being photographed, as they did not include any visible embryo or fetus.

According to the New York Times article, when a manual uterine aspiration procedure (one method by which a doctor can perform an abortion) is conducted, the procedure only takes a few minutes in an exam room. After the procedure, the tissue taken out is routinely examined, and at this point during pregnancy, “the embryo is not typically visible to the naked eye.”

Due to the stigmatization of abortion and misinformation spread on fetal development during early pregnancy, often by Christian pro-life organizations, many patients are surprised when they learn there were a few different types of tissue, not a tiny fetus shaped like a baby, inside them. And for many, learning this takes away the feeling of guilt from the early-term procedure.

Referenced in the article as “Jewel,” one patient who received an abortion in New York after not being able to access one in her home state of Texas said she felt relief after seeing the tissue. She said the anxiety leading up to her appointment was “worse than actually going through it.”

Religious liberty and abortifacient distribution

Questions posed for discussion in a post-Roe America not only touch on biology and medical practice but also religious liberty.

If the right to abortion care is not protected by the federal government, but religious freedom is, what does that mean for religious health care providers who see patients with prescriptions relating to reproductive health?

A publicity photograph put out by Robyn Strander’s law firm, First Liberty Institute.

On Jan. 11, nurse practitioner Robyn Strader filed a lawsuit against CVS Health Corp. after the company ended a six-and-a-half-year-long religious accommodation that allowed her to avoid prescribing contraceptives and abortifacient drugs to patients based on her Christian faith.

Strader, a member of a Baptist church, believes that because all human life is created in God’s image, she “cannot participate in any way in facilitating use of contraceptive or abortifacient drugs.” This means it contradicts her religious beliefs to distribute these drugs to patients.

During the time she worked at a CVS pharmacy in Fort Worth, Texas, Strader reportedly utilized her religious accommodation to refer patients seeking these drugs to other pharmacists, either by having patients serviced by other pharmacists at her location or by referring them to a pharmacist at a nearby CVS.

In August 2021, following a CVS Health Corp. policy change, Strader was informed she no longer would be granted religious accommodations for the distribution of hormonal contraceptives.

Strader was informed if she did not agree to fill prescriptions for hormonal contraceptives, she would be fired the following month.

Strader contends she made multiple attempts to contact CVS, asking how to reinstate the accommodations made upon her hire, but she received no answer. In September 2021, Strader was informed if she did not agree to fill prescriptions for hormonal contraceptives, she would be fired the following month.

On Oct. 31, 2021, Strader was fired from CVS. She alleges she never received a response to three letters that were sent (between August and October) asking for religious accommodations.

Her lawsuit argues that CVS’s refusal to reinstate Strader’s religious accommodations is a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, which states that if a religious accommodation can be made for employees “without undue hardship,” employers must make it.

Although Strader was fired before Roe v. Wade was overturned, her new lawsuit poses some interesting questions in discussions about medical care. Among them: Where is the middle ground?

Middle ground?

Should medical providers be able to deny services to patients because they fear it is a sin to participate in or facilitate the process of abortion broadly defined? And should patients have to worry about encountering a pharmacist who will judge them or deny otherwise legal services?

Patients do not come to pharmacies to be evangelized but to seek care. If medical providers are allowed to discriminate in care based on religious beliefs, patients who have opposing beliefs on issues like abortion may have a hard time finding care that honors their own religious liberty. Further, if religion is brought into question, some patients may choose not to seek life-saving abortion care after feeling ashamed that a Christian doctor refused to fill their abortifacient prescription.

If a pharmacist, like Strader, believes providing certain medications is a sin, is it a violation of religious liberty if their employers refuse to accommodate their religious beliefs? Is it even plausible for these accommodations to be carried out “without undue hardship” while maintaining high patient care standards?

As new legislation offers less protection for patients seeking abortion care, the line between professional medical practice and religious liberty becomes less distinct. Will this lawsuit, without the power of Roe v. Wade, pave the way for medical providers to choose what services, procedures and medications patients receive based on belief, instead of medicine?

As post-Roe abortion laws become both more strict and more vague, moral questions pile up. And Christians looking to take a stance on this issue must learn how to balance religious liberty with medical freedom — patient rights against provider rights.

Mallory Challis is a senior a Wingate University and serves as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

As more Americans delay health care they can’t afford, it’s time for the church to be a light once again | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Can Christians come together to reduce the need for abortion? | Opinion by Susan Shaw

Why I’ve never written about abortion before now | Opinion by Mark Wingfield