When COVID-19 started to spread, epidemiologist Emily Smith expected the pandemic would provide an opportunity for Christians to shine the light of compassion into the lives of hurting people.

But when Smith began writing a blog to help focus that light, she experienced a dark backlash of denial, anger and vitriol she never anticipated.

Smith serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine/Surgery at Duke University and in the Duke Global Health Institute. She joined Baptist News Global’s Mark Wingfield in an Oct. 17 “change-making conversations” webinar to discuss her new book, The Science of the Good Samaritan: Thinking Bigger about Loving Our Neighbors.

Smith’s calling to epidemiology — the branch of medicine that deals with the causes, spread and control of diseases and other health factors — developed naturally out of her Christian faith, she said.

Wanted to be a missionary

She grew up in a tiny town in Southeastern New Mexico, where her parents led worship in their small church and her family frequently hosted visiting missionaries. Dinnertime conversations gave her an opportunity “to just drill them with 8-year-old’s questions” about their travels, their ministry and the people they knew.

Emily Smith

“I wanted to be a missionary growing up,” she recalled. And even though that didn’t happen, the passion “to do something in the globe that would help people” stuck with her.

Smith began defining that passion as a pre-med student at Wayland Baptist University, when she spent a summer with Mercy Ships off the coast of Honduras. “That was my first look into the world of poverty,” she said. “And I noticed I was asking questions that were different” than questions asked by medical personnel.

“They asked questions of one-on-one treatment, and I noticed I was asking questions about poverty: Why is this group of children so sick with pneumonia, but this group isn’t? I didn’t know it at the time, but that’s epidemiology.”

She got into medical school but took a gap year because her husband, a pastor, accepted a call to a church across the country. So, she decided to spend the year working on a master’s degree in public health.

“On Day 1 of (the introductory course in) epidemiology — which I hadn’t heard of at the time — I recognized: ‘Oh, this is just me. It fits what I was asking.’ So, I pivoted and got a Ph.D.” in epidemiology from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Faith and science

Given her religious background — “I am very motivated by my faith to help, not as a white savior but as a person walking alongside others,” she acknowledged — Smith’s chosen vocation caused her to work at the intersection of faith and science.

“My way to act like Jesus in the world was through data and epidemiology.”

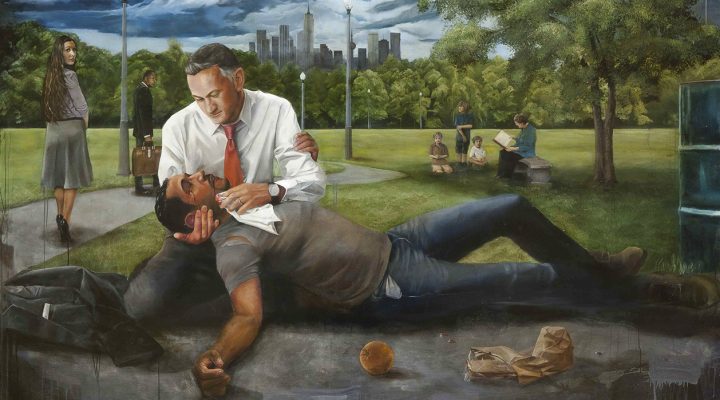

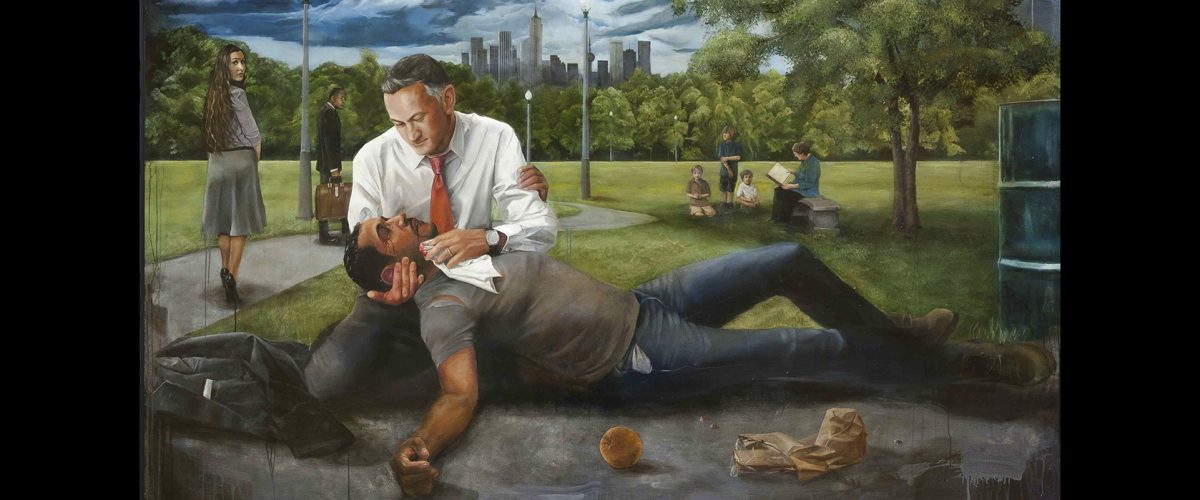

“I remember thinking: ‘Oh, that’s the science of the Good Samaritan. It’s quantifying who is most at need and then choosing not to walk by,” she explained. And although she has been careful not to press her faith onto others, she soon realized “my way to act like Jesus in the world was through data and epidemiology.”

In her case, faith and science propelled her to work alongside some of the world’s most at-risk and marginalized people.

“I think my personality is fairly tender, really very empathetic, so I tend to gravitate to the margins and to those who are on the side of the road” like the injured man in Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan, she said. “I’ve always just wanted to help in whatever way I could.”

That came to the fore as the COVID pandemic flared up.

“In 2020, I spoke at two big conferences when Wuhan (the start of the pandemic) was happening,” she said. “So, there were a lot of people asking questions. And then, when I went back home, my neighbors and people in my family began asking, ‘What does “flatten the curve” mean?’”

A blog is born

In response, she launched her blog, Friendly Neighbor Epidemiologist, to answer questions (such as, “Should we buy a billion things of toilet paper?” which the answer was, “No!”) she already was receiving from family, friends and neighbors. People the world over looked to her for answers; the blog peaked with 106,000 followers, reaching 10 million people during the height of the pandemic, and has remained steady.

Smith entered the pandemic and launched her blog with naïve hope, she reflected.

“I just thought this was going to be the time for the church to really shine with the solidarity of love for neighbor.”

“I just thought this was going to be the time for the church to really shine with the solidarity of love for neighbor,” she recalled. “But I didn’t start (the blog) for the church. I started it just to be global neighbors to one another. My day job is to work in places like Somaliland and Burundi on poverty and children’s health. So, I had known enough history about global health that I knew how Americans were going to act and hopefully would affect our friends and neighbors in Somaliland and Burundi.”

But Smith “ran into a buzz saw,” Wingfield observed.

“It started pretty early on,” she agreed. As a pastor’s spouse, she wanted to help pastors help their congregants navigate the pandemic. But she quickly received pushback from pastors who were telling church members, “‘Have faith, not fear,’ which was code in some places for ‘Don’t wear your mask; trust the Lord’” she said.

“That is wacky Bible. I just couldn’t understand it,” she added, recalling she wrote a blog asking pastors to help congregants understand what “faith over fear” actually means, citing passages about love for others from the Apostle Paul and the Good Samaritan parable.

“That is wacky Bible. I just couldn’t understand it.”

“That was the first time where the backlash happened,” she said. “And around that time is when we got our first threat at the house,” which was “the scariest day ever, because it was written in red and black marker, and it was fraught with Mark of the Beast and awful stuff about my family and my kids. … I thought at some point this has got to stop, and it got worse.”

The Smiths received death threats, and they couldn’t let their children, ages 12 and 9 at the time, walk in their own neighborhood without one of the parents going with them.

“We also were starting to get some awful harassment from people we worshiped with or who were in our own neighborhood, and that’s when it got really scary,” she said. “Anybody can send a picture of a gun, … but when (the threat) comes from close by, that was really, really scary.”

“It also showed me how I don’t think Christian nationalism is fringe,” she added. “I absolutely do not think it’s fringe. We saw it in just our little neighborhood” in Waco, Texas, where she taught at Baylor University at the time.

Three kinds of response

In overall response, Smith’s “Friendly Neighbor Epidemiology community” split into three groups, she reported. The science group, which comprises about 50% of the total and includes people of various faiths, was fine with her blogs. But the Christian group divided into two other groups.

“One of them just dug their heels in more to ‘We’re not going to wear a mask’ and ‘We’re going to believe’ all the wackadoodle stuff they see on Facebook. The other group said, ‘I have never seen systematic racism before’ or ‘I’ve never heard of structural violence’ or ‘I’ve never seen poverty’ or fill in the blank. But now that I do, I want to act like a neighbor better.”

Smith received vigorous opposition from pastors, the people she particularly was trying to help.

“It was more than just surprising,” she said. “It was devastating, because I hadn’t really had losses like that — losses of friendship, loss of a faith community, loss to myself and my children and my husband.”

“My body just said, ‘No more’ and gave out on me completely.”

Eventually, the shock and grief and stress took a toll. The week after Easter of 2021, “my body just said, ‘No more’ and gave out on me completely,” she explained. “I got what they call an unrelenting chronic migraine, and it did not let up for months and months and months.”

Three themes

What happened to Smith and her family illustrates one of three major themes of her book — cost. The other two are centering and courage.

“I wanted to write a book not about COVID-19, but about what’s next. How can we be neighbors in a world set up to do quite the opposite?” she said, noting the natural starting point is centering, which provides “a foundation to be neighboring.”

The key to centering is looking to Jesus and seeing who Jesus placed in the center of his attention, she said. “He centered the kiddos, or he stopped the entire crowd because of the bleeding and impoverished woman, or he centered the lepers. He flipped who should be in the middle of our attention on its head.”

“We can do that, too, in today’s world” by focusing on people on the margins of society and on poverty, she added. “We can be better global neighbors. I hope this book helps people understand how to do just that by understanding historical inequities, systemic racism and structural violence through storytelling and data. I also hope it can help places of worship have these conversations in nonthreatening but challenging ways in their own congregations.”

Because living out the Good Samaritan parable is costly, it requires courage, Smith said. She pointed to the ancient Hebrew leader Nehemiah, who rebuilt the Jerusalem wall and exercised courage by refusing to be intimidated and distracted from his task.

“That is such an anchor for me — to not get distracted by voices I don’t need to be distracted by or fights I don’t need to enter,” she said. “The Nehemiah type of courage is the wisdom to know what is my good work and what isn’t. For a lot of us, when we start seeing systemic racism, and then you have climate change, and then … poverty and children’s health, you can’t do it all. … It is a call to action, not exhaustion.”

The Science of the Good Samaritan will be released Oct. 24 and is now available for pre-order. Study guides for nonfaith and faith groups will be available.

Watch the full webinar video here.

Related articles:

Your friendly neighbor epidemiologist has an important message for you

To the shepherds: Reframing Christmas in a pandemic

One year later, letting go of ‘what used to be’

New data on COVID vaccine efficacy is good news for faith leaders seeking to be influencers

If you think we’re out of this pandemic, take a look at the rest of the world

Evangelical leaders explain why skeptical evangelicals should get vaccinated