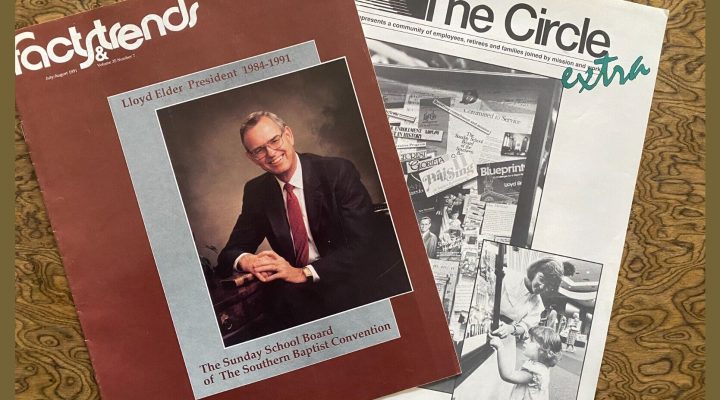

Southern Baptist statesman Lloyd Elder died Nov. 3 at age 90.

Elder was the last “moderate” leader of the Southern Baptist Sunday School Board, forced out in 1991 by trustees elected through the “conservative resurgence” that had begun in 1979.

In February 1984, he was elected to the high-profile post without opposition. Seven years later, as the politics of the convention had turned and trustees had been replaced, he did not have enough board support to continue.

Gene Mims, who was a trustee when Elder was forced out and later became a vice president of the massive publishing house, said of him in 2002: “He came to the board during the time of the greatest modern upheaval. He came during the time of a changing board of trustees, a changing convention, a changing institution. During this time, he worked tirelessly to do what he could. He often said that he would do what he could do with what he had for as long as he was given. We learn from him the ethic of hard work and kingdom focus in difficult times.”

Lloyd Elder

Indeed, Elder’s tenure leading the Nashville-based publisher of curriculum and books and sponsor of workshops, conferences and camps, paralleled the most contentious era of the denomination’s turn to the right theologically and politically.

His departure came just six months after the two editors of Baptist Press, the SBC’s in-house news service, had been fired as part of a campaign led by Paul Pressler, one of the co-architects of the conservative movement. Agency leadership changes were commonplace in those days, as new conservative majorities took control of trustee boards and enacted their will.

The SBC’s Home Mission Board already had gained a conservative leader four years earlier. The president of the SBC’s Foreign Mission Board would take early retirement the next year. The denomination’s ethics agency had experienced a leadership change in 1988. And a series of leadership changes were sweeping the SBC’s six seminaries — some through normal retirements and some through firing.

At the time of his negotiated early retirement, trustee leaders said Elder’s departure was not due to theology or politics but was about “management style, philosophy and performance.” He was succeeded, however, by one of the pastors who had led the conservative resurgence as convention president, Jimmy Draper.

“Lloyd Elder was the kind of leader who helped shape the Southern Baptist Convention back in the day. Unfortunately, there came a day when his kind of leader was no longer appreciated,” said Gary Cook, who served as a vice president with Elder at the board. “As a result, he was cast aside. Lloyd Elder,being the kind of man he was, stayed in Nashville and watched up close and personal what happened to Southern Baptists. In all the conversations we have had, since we both were no longer employed by the Baptist Sunday School Board, I never heard him utter a harsh word concerning those who cast him aside. That was Lloyd Elder.”

Elder had been a target of conservative trustees for at least three years prior to his departure, with an unsuccessful effort to oust him made in 1989.

At his election in 1984, he had described his belief in the Bible as “a holy book, divinely inspired by God, infallible and authoritative in the life of every believer.” The conservative movement in the convention was built around a rallying cry of biblical inerrancy, however, and new trustees were frustrated Elder would not declare himself an inerrantist.

His tenure at the Baptist Sunday School Board — later renamed Lifeway Christian Resources — was at the final peak of post-war denominational loyalty.

His tenure at the Baptist Sunday School Board — later renamed Lifeway Christian Resources — was at the final peak of post-war denominational loyalty, when SBC churches nationwide purchased nearly everything the board put out. In 1984, guests could walk into any SBC church anywhere in the nation and most likely find the same Sunday school curriculum and study books from their home church.

By the time of Elder’s exit in 1991, that denominational loyalty was fading fast. Conservative churches were buying curriculum and books from a new array of parachurch ministries, and more progressive churches founded their own curriculum publishers as they lost faith in the SBC.

Elder came up through the ranks of denominational leadership, beginning as a bivocational pastor. He came to the Sunday School Board post from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, where he was executive vice president. Before that, he served as assistant to the executive director of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. And before that, he held pastorates at First Baptist Church of Holland, Texas; First Baptist Church of Princeton, Texas; First Baptist Church of College Station, Texas; and Gambrell Street Baptist Church in Fort Worth, across the street from Southwestern Seminary.

After leaving the Sunday School Board, Elder joined the religion faculty at Belmont University in Nashville, filling the Paschall Chair for Biblical Studies and Preaching. He later was named director of the Moench Center for Church Leadership at Belmont.

At the time of Elder’s second retirement, Steve Simpler, then dean of the School of Religion, said of him: “Lloyd has helped us maintain a healthy balance between church and academic life at Belmont. He is the classic example of a pastor-theologian. He has distinguished himself as a respected religious leader, yet he doesn’t take himself too seriously. I’ve been with him at Moench Center workshops in rural churches where we had half a dozen people. I’ve been with him when he led worship at large urban churches. He’s the same guy in both places. He’s a genuinely good person who reflects God’s grace.”

After that stint at Belmont, Elder still wasn’t done. In his final position, he served as volunteer administrator and chair of the development board of the Bivocational and Small Church Leadership Network, based in Nashville, Tenn.

Memorial arrangements are still pending at this time. This story will be updated as new information becomes available.