The wind was rushing so strong that it sounded like someone left water running outside as I woke up early last Friday morning.

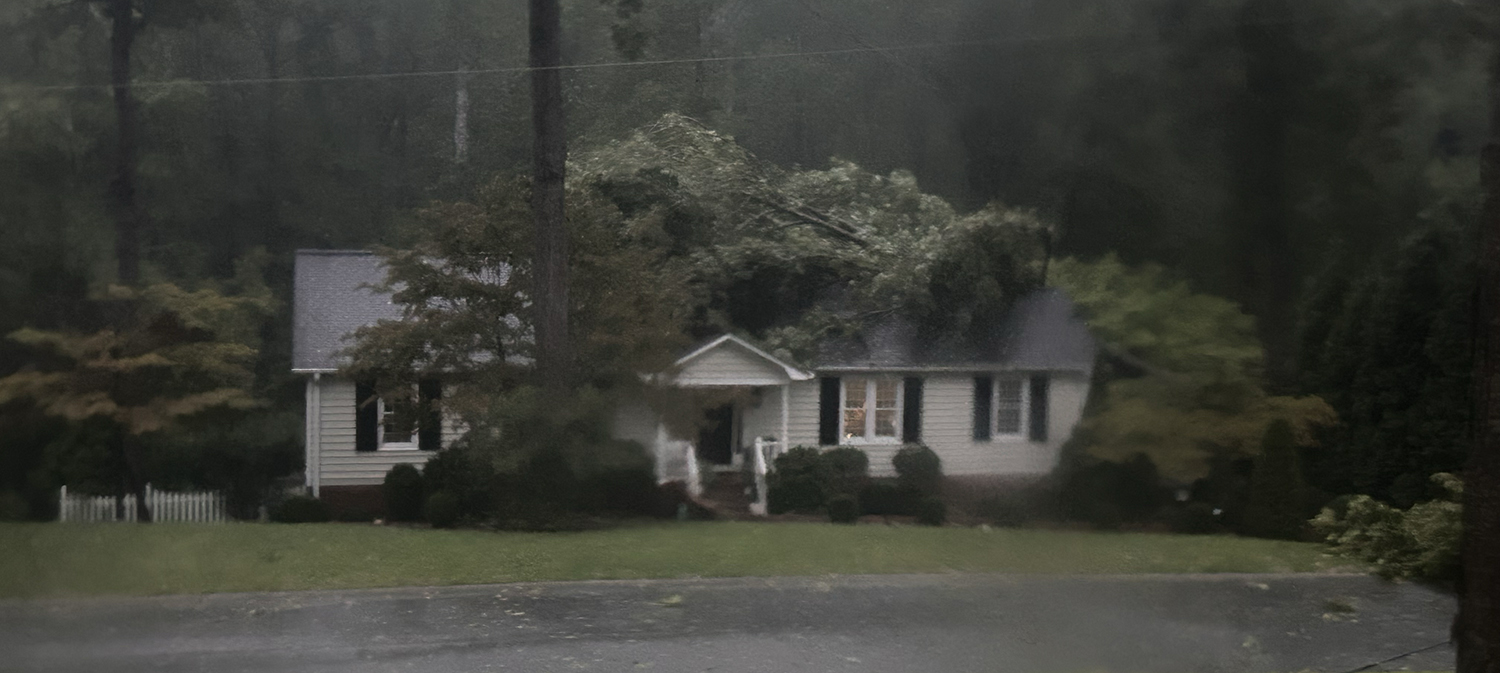

When our kids found their way through the dark house to our room, we looked out the window to see what was going on. Directly across the street, a large tree was laying on top of our neighbor’s house, allowing the rain to pour in. We later learned the woman who lives there was huddled in a room with her daughter, hearing sounds of the storm pouring inside their house.

Then when we turned to our right, a giant oak had been ripped from the ground and fell across the road. That’s when we knew this storm was going to be far worse than anything we’d ever experienced in the upstate of South Carolina.

Rick Pidcock

As somebody was knocking on our neighbor’s door across the street, we saw an emergency vehicle slowly approaching the tree from the other side, with no ability to pass. With wind gusts approaching 70 mph, I wondered if at any moment one of our century-old oak trees might crash into our house with us inside. And we were surrounded by them.

Hurricane Helene dumped more than 40 trillion gallons of rain in its nearly 350-mile-wide wind path. It takes 619 days for that much water to flow over Niagara Falls. According to the Associated Press, it was as if Lake Tahoe dropped out of the sky.

Ed Clark, head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Water Center, said, “I have not seen something in my 25 years of working at the weather service that is this geographically large of an extent and the sheer volume of water that fell from the sky.”

With the soil saturated, trees that were not used to Helene’s high sustained winds didn’t have a chance.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp compared the winds approaching 140 mph to a 250-mile-wide tornado.

In Tennessee, people fled due to the threat of dams breaking, while hospital patients had to be airlifted by helicopter due to waters rushing in.

In South Carolina, firefighters were killed as trees fell on their truck during a call, while others died due to trees crashing onto their homes.

In North Carolina, mountains gave way to landslides and flash floods as roofs collapsed with people on top, causing them to drown. With rescue efforts underway, bodies have been found in trees. Entire communities have been washed away.

To make matters worse, many people in the region lost cell phone coverage, keeping them from being able to contact loved ones, call for help or have any idea what’s going on.

And even for those whose homes have remained intact, the amount of work needed to restore power is unprecedented for this area. For the Duke Power customers in the upstate of South Carolina, which is just one of the power companies, more than 6,000 power poles have been damaged and need to be replaced.

But most tragic of all, at least 200 people have died, and 600 are still missing.

Loving your neighbors

After the rain subsided and the winds began to slow, our neighbors ventured outside to see what happened. Of the four houses closest to ours, three had trees on top of their homes. One of our neighbors had both vehicles smashed. Our entire neighborhood was completely trapped, with nobody able to come in or get out.

City crews were pulled off the streets for safety concerns after one of the crews almost was hit by a falling tree. So it was going to be up to us to clear the roads.

The sound of chainsaws and bobcats began to fill the air as everyone pitched in to remove the trees from the roads. For the first couple days, there were only a couple ways to get out of the neighborhood. And it required weaving through tight spaces between the downed trees and power poles, with power lines tangled amidst the rubble.

“While some worked on the trees, others made coffee on their grills and delivered it to the neighbors.”

When I walked the neighborhood a few days in, the one statement I kept hearing from neighbors was, “It looks like a bomb went off.”

While some worked on the trees, others made coffee on their grills and delivered it to the neighbors. Others worked together to repair someone’s sump pump. Because the city would remove only the trees near the road, neighbors with chainsaws went house to house to cut trees and move them.

Those who still had trash cans shared with those whose trash cans were smashed. Those who had generators shared refrigerator space with others who needed to store refrigerated medications. Someone who had a drone camera took photos of the damage for people to send to their insurance companies. And as people got their own homes and yards under control, they began collecting supplies to drive up to Asheville, N.C., and the surrounding towns that had been wiped out to share with those in need up there.

As I walked down a dead-end street where a large tree had fallen across the road, I decided to check the other side where there was one last house. And there on the ground was an old woman, probably in her 80s, with her husband sitting next to her. He wasn’t strong enough to lift her up. So he asked if I could lift her up and put her in her wheelchair. Because they were the final house on the other side of a tree, who knows how long they would’ve been sitting there in the sun had I not walked around the tree.

How we talk about God amidst our neighbors’ suffering

While it seems every city from here to Dallas thinks they’re living in “the buckle of the Bible Belt,” the reality is that probably any of us could claim that title given the number of Christians and churches we have. So I know many of my neighbors who are helping one another are Christians, and many may be motivated by their faith as they share coffee or move trees for their neighbors.

As long as Christians are identifying with their neighbors as fellow sufferers and moving toward one another in acts of kindness, the presence of love has bonded us together despite whatever political, cultural, economic, theological or personality differences we may have.

But what’s been frustrating for me has been noticing the moment Christians begin importing their languages of hierarchy into the conversation. Hierarchy always produces exile toward those who won’t fit themselves into the hierarchy. And this never has been more clear to me than in observing how some of my neighbors have talked about God amidst this unprecedented disaster for our area.

One posted online, “I am thankful for God’s protection of his people (and unbelievers too!)”

While I can understand being thankful for not getting hurt or killed, why differentiate between “his people” and “unbelievers” and then put “unbelievers” in parentheses? This is a classic conservative evangelical Calvinist language that makes those of us on the outside of God’s supposedly chosen few feel like second-class citizens.

Another one posted, “I’m thankful that my home wasn’t damaged and that God kept me safe through it.” Then someone replied, “God kept you, huh? Must be nice. He must have totally ignored vast majorities of other of his/her children in the area.”

A video was posted of a famous wedding chapel nearby called “Pretty Place” that has a cross overlooking the upstate. Part of the roof collapsed, while the cross stayed upright. So neighbors began posting, “The cross stood strong!”, “The Cross!!!”, “The cross is still standing, Amen, Amen!!”, and “The cross still stands!”

So apparently, God doesn’t care about kids in their homes, but cares about protecting a cross out in the middle of nowhere.

Someone else said they were thankful God made a tree fall the opposite direction of their home. So then another less fortunate neighbor responded by asking if God made their tree fall on their home.

“It’s harder to recognize as hierarchy because it’s framed as thankfulness and praise rather than as the sacralization of power.”

Then when news came out about an elderly couple that was crushed and killed in their bed by a tree, someone responded by saying, “Maybe it was God’s plan to take them together.”

These examples are expressions of hierarchy that may be more difficult for some Christians to notice as hierarchy than the typical conversations about power that promote white male supremacy over women. It’s harder to recognize as hierarchy because it’s framed as thankfulness and praise rather than as the sacralization of power.

But when you examine what’s being said, it’s depicting God as a being up there who is controlling where trees and old ladies fall. In other words, God’s presence is one of dominion over us to spare some and violently hurt others. Did God smash your bedroom and kill your dog? Did God drown your child? Did God push over the elderly woman who I helped up?

All this language is completely unnecessary. And it not only feels belittling to those of us who don’t accept this theology and thus are exiled to the parentheses as “unbelievers,” but it creates a really unloving picture of God and fosters a hardened heart toward suffering in those who believe and celebrate it.

Spreading conspiracy theories

Of course, in today’s world of Christian nationalism and QAnon, this conversation wouldn’t be complete without noting the spreading of conspiracy theories. After spending almost a week in a house with five kids and still no power, I don’t have the energy to debunk each of these.

But some of the conspiracies I’ve seen from people in my city, many of whom I know to be Christians, are that the government has patents for weather modification and that Joe Biden created Hurricane Helene to target pro-Trump counties, that the elites are brewing storms in the Atlantic, that Biden created the storm to distract people from the economy, that the government was able to keep the eye of the storm intact through three states, that researchers are experimenting with cloud seeding, that it’s spiritual warfare being waged by demons against Christians and Trump supporters, that local government officials in the upstate of South Carolina and in North Carolina caused the hurricane in order to get the funding to change our cities into “Smart Cities,” and that there was a sonic boom in the hurricane.

God with us

So where exactly is God in all of this? Does that even matter? And do Christians have any theology worth considering that might be helpful during times of suffering?

The theologians of white evangelical Calvinism want us to imagine God at the top of the hierarchy smashing houses with trees, pushing over old women, and drowning children for self-glory, while protecting “his people.”

But Black liberationist theologian James Cone imagined God on the underside of power, in and among those who are suffering. He said, “The Christian gospel is more than a transcendent reality, more than ‘going to heaven when I die, to shout salvation as I fly.’ It is also an immanent reality — a powerful liberating presence among the poor right now in their midst.”

He also said, “Knowing God means being on the side of the oppressed, becoming one with them, and participating in the goal of liberation.”

Perhaps this is what Jesus meant when he said, “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

This is why recognizing the language of hierarchy is so important. If we imagine God at the top exercising dominion over lesser beings by crushing and killing us, then we’ve essentially turned the Trinity into the divine imperial family of ancient Rome. Thus, participating with that god’s work in the world would be to become complicit in the sacralization of dehumanizing power. This is incompatible with loving your neighbor as yourself.

But if we imagine God on the side of the oppressed, if we consider “God with us” to mean God on the ground, then participating with that God’s work in the world would look more like making coffee on your grill and sharing it with your neighbors, working to repair sump pumps, removing trees, sharing trash cans or refrigerator space, taking pictures for insurance claims, collecting supplies to assist those even less fortunate, and helping lift an old woman off the ground into her wheelchair.

A few miles into my walk through our neighborhood, I came across our cemetery. During the Civil War, the land we live on was home to both rich and poor, slaveowner and slave. So our neighborhood cemetery includes a combination of tombstones commemorating the lives of those whose names are still remembered in our community, as well as unmarked graves of unknown slaves. But no matter their lot in life, eventually they all suffered and died. No matter what differences they had, their suffering and death is what they had in common. And now they lie together in the ground with many of their tombstones crushed.

A few miles into my walk through our neighborhood, I came across our cemetery. During the Civil War, the land we live on was home to both rich and poor, slaveowner and slave. So our neighborhood cemetery includes a combination of tombstones commemorating the lives of those whose names are still remembered in our community, as well as unmarked graves of unknown slaves. But no matter their lot in life, eventually they all suffered and died. No matter what differences they had, their suffering and death is what they had in common. And now they lie together in the ground with many of their tombstones crushed.

No matter what I think about my neighbors’ theology or politics, the exile we feel happens when some of us use language of sacralized hierarchy, while the union we have is in our common suffering.

What if the same exile and union could be experienced with God? What if God were present in the loving of neighbor as self during our common suffering?

The healthiest Christian theology fosters wholeness, not by imagining a God who pushes us down and drowns our kids, but by imagining a God who suffers with us, in and among the oppressed. So every morning, when I walk outside and notice the power line still down in our front yard and hear the sounds of chain saws revving up through the trees in the surrounding acres, that’s where I consider God to be — in the sounds of a communion of liberation.

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

Disasters bring out the best and worst theology | Opinion by Paula Garrett

In Helene’s path, churches swing into action with relief ministries