On Tuesday, Jan. 10, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors declared a local state of emergency on homelessness.

This follows last month’s action by Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, when on Dec. 12 she declared a city-wide state of emergency on homelessness in response to the severity of the current housing crisis. This was the first declaration of a local state of emergency due to homelessness in Los Angeles since 1987.

Now, county officials are recognizing the problem on a larger scale, seeking to work with city officials to find places to live for more than 69,000 unhoused residents in Los Angeles County. The declaration will allow county officials to bypass lengthy bureaucratic processes that slow their ability to mend the problem.

For example, they are now able to speed up the hiring process for essential personnel who can aid the unhoused seeking services from county offices, such as counselors in the Department of Mental Health.

In addition to offering more services, the county is utilizing its resources to “accelerate the creation of licensed beds, interim housing and permanent housing” in an effort to ensure as many people are indoors as possible.

A jogger runs past a homeless encampment in the Venice Beach section of Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

Across the rest of America, unhoused people are visible in every city, in every county and in every state. And it has been this way for quite some time. Homelessness is not a new phenomenon that has only plagued Los Angeles County.

This is a serious and growing issue in city after city. So, why declare a state of emergency now? And why is this problem so extreme in Los Angeles?

Los Angeles County is the second-largest metropolitan area in the United States. In July 2021, the U.S. Census estimated there are about 10 million people who live there. During that year, 14.1% of the population was believed to live in poverty.

However, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority recently released their 2022 Homeless Count, which estimated the number of unhoused people at 69,144, with 41,980 of those people living within the city of Los Angeles.

Countywide, this is a 4.1% increase since 2020. Citywide, it is a 1.7% increase. Even though these numbers are incredibly high, the rate of increase has dropped in the past few years. In the same report, LAHSA states that between 2018 and 2020, the county experienced a 25.9% increase in unhoused people and the city recorded a 32% increase.

So, while the number of unhoused people in Los Angeles continues to be a serious problem, there are data suggesting the curve is flattening.

Over the past five years, LAHSA has made 84,000 permanent housing placements for unhoused people across LA County.

Having a direct impact on these numbers is LAHSA’s efforts to provide permanent housing to the unhoused. Over the past five years, LAHSA has made 84,000 permanent housing placements for unhoused people across LA County.

The homeless count also noted that, although there have been more tents, vehicles and makeshift shelters in LA County since 2020, the actual number of people living in them only rose by 1%. This is likely due to the CDC’s guidance not to remove encampments, even if they are vacant, so unhoused people can socially distance to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This gives off an illusion to passersby that there are more unhoused people living in shelters than there really are. So, while homelessness is still very prevalent, it may not be as prevalent as it looks from the outside.

On the other hand, as COVID-19 emergency measures come to an end, the curve may become steeper once again, and the number of people using these shelters may rise even higher.

This is because one-time federal assistance and local economic policies that were temporarily put into place during the pandemic, such as eviction moratoriums preventing landlords from removing tenants for non-payment of rent, helped people who otherwise would have become unhoused keep their homes.

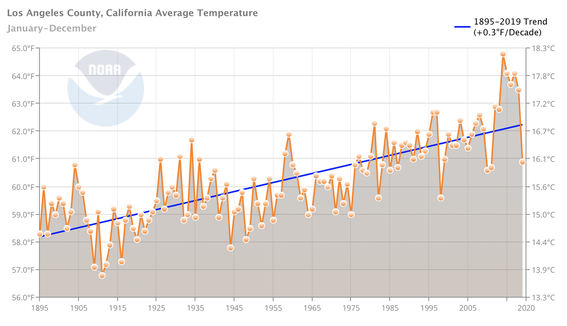

Aside from organizational and governmental measures, another aspect of life unique to Los Angeles exacerbates the problem of homelessness: Climate.

Unlike other parts of the U.S. where there are networks of support in place for the unhoused to protect them from the dangers of brutally hot summers and icy cold winters, California’s historically temperate climate has created a particularly dire problem as temperatures begin to rise and fall to extremes due to climate change.

LA County’s temperate climate, mixed with its large population and high cost of living, creates the perfect place for a large amount of unhoused persons to believe they can successfully live outside.

However, as average temperatures have begun to rise, the unhoused population is having a harder and harder time living safely outdoors.

Their investigation uncovered six times the number of deaths related to extreme heat than the state was reporting.

In a 2021 investigation, the Los Angeles Times discovered about 3,900 people in California died of extreme heat between 2010 and 2019. Their investigation uncovered six times the number of deaths related to extreme heat than the state was reporting.

Given this data, it is clear the current state of emergency is responding not only to the number of unhoused people in Los Angeles, but to a complex set of issues that have brought unhoused persons to a point of endangerment.

While the climate is currently temperate in winter, those losing housing arrangements today may not find it difficult to live outdoors. However, as summer comes closer, hotter temperatures will put those in shelters or on the streets at risk of heat exhaustion, heat stroke and other heat-related illnesses that may lead to death.

Thus, emergency measures that prioritize permanent and interim housing availability for the unhoused are important right now.

In addition to other forms of government and community aid, such as indoor spaces that allow the unhoused to cool down during the day or access to medical care, keeping people indoors will prevent deaths in Los Angeles.

And in the long run, providing a clean and safe living space for the unhoused will facilitate their ability to support themselves in various ways without having to worry about the risks and dangers of life on the streets.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

Faith-based groups lead the way in serving nation’s homeless

What churches should know — and do — about a homelessness problem you likely didn’t know about | Analysis by Kristen Thomason