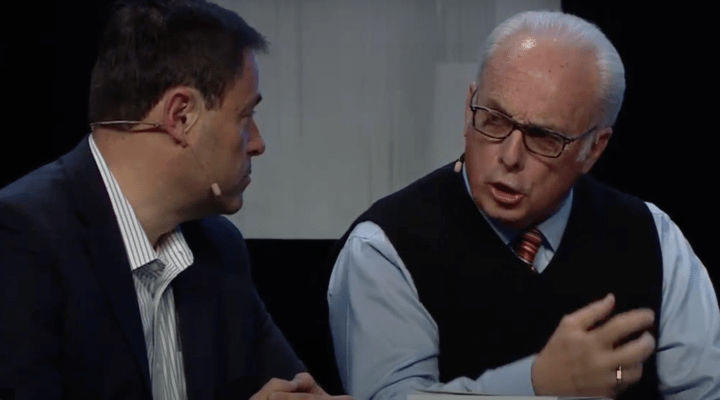

Two conservative pastors, two different approaches to protesting COVID-19 health restrictions on public gatherings, with two very different outcomes. This is the story of John MacArthur and Mark Dever.

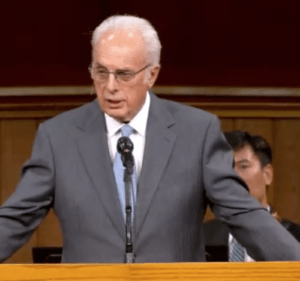

Throughout the summer, MacArthur, pastor of Grace Community Church in Los Angeles, has been in a litigious battle with Los Angeles County over the county’s public health restrictions against large indoor gatherings. Despite a restraining order entered against the church by a Superior Court judge, MacArthur has defiantly held indoor services with thousands of unmasked, un-distanced worshipers. The county is currently seeking to have the church and its leadership held in contempt of court and fined or jailed.

Almost as far away from Los Angeles as one can go in the continental United States, Dever has taken a different — and now more successful — approach with the District of Columbia government.

Late on Friday, Oct. 9, U.S. District Judge Trevor McFadden granted relief to Dever and Capitol Hill Baptist Church in their request to be allowed to conduct outdoor worship services in the District despite the local government ban on such assemblies.

Two approaches by two pastors

John MacArthur preaches at Grace Community Church on Sunday, Aug. 16, in defiance of a court order on public health.

The differences between the two cases and the approach of the two pastors are considerable. MacArthur has been combative and defiant from the start. And even now, while still embroiled in legal battles, he has released a video calling on other pastors across the country to “open your churches.” Dever has stated his case more calmly, without making threats or inciting other churches to follow his lead.

MacArthur has seen Los Angeles County’s ban on large indoor gatherings as persecution of the church and built his case on this persecution complex. Dever has stated a unique theological conviction that biblical worship must be held in-person, not via video or even in multiple services.

MacAthur has refused county officials suggestions for compromises such as holding outdoor gatherings. Dever has sought to find a compromise with unbending government officials and has, in fact, been holding outdoor gatherings in nearby suburban Virginia.

MacArthur’s church is located in perpetually sunny Southern California, where outdoor gatherings are possible most Sundays of the year, yet refuses to yield to that format. Dever’s church is located in the less temperate climate of the Mid-Atlantic, yet has asked only to be allowed to have outdoor services.

Mark Dever

Both pastors and their congregations have appealed to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, legislation passed by Congress in 1993 that says government may only restrict the free exercise of religion when it has a compelling governmental interest to do so, and it must take the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.

The Superior Court judge in California determined MacArthur and his congregation are not likely to prevail at trial basing their claim of persecution on RFRA, in part because churches have not been singled out for treatment different than other similar assemblies such as theaters and music performance venues and because other viable alternatives to indoor assemblies are available. The federal District Court judge in D.C. determined Dever and his congregation are likely to prevail in their RFRA claim, and therefore granted temporary relief to the church.

The D.C. ruling

In D.C., Dever made a unique case that his congregation’s theological belief is that to fulfill the biblical mandate of “assembling together,” they must meet in person and in one service. Prior to COVID-19, Capitol Hill Baptist Church held only one Sunday morning service, did not offer a livestream and did not employ multi-site campuses.

That gave an opening for Judge McFadden to differentiate the claim of the D.C. church against any other such cases nationwide.

“For its part, the District does not dispute the sincerity of the church’s belief that its members must gather together in person for worship,” he wrote. “Rather, it maintains that the church has nonetheless failed to prove that the District’s restrictions have substantially burdened the church’s religious exercise — particularly where there are other ‘methods’ of worship available. The District proposes that under its current restrictions the church could ‘hold multiple services, host a drive-in service, or broadcast the service online or over the radio,’ as other faith communities in the District have done. But the District misses the point. It ignores the church’s sincerely held (and undisputed) belief about the theological importance of gathering in person as a full congregation.”

“The District misses the point. It ignores the church’s sincerely held (and undisputed) belief about the theological importance of gathering in person as a full congregation.”

One of the tests of RFRA and subsequent court rulings is whether a government restriction has placed a “substantial burden” on the free exercise of religion. McFadden said in this one congregation’s case, the burden placed on the church is greater than the need of the government to create the restriction.

“The District may think that its proposed alternatives are sensible substitutes,” he wrote. “And for many churches they may be.” But it is not for the District to say that the church’s religious beliefs about the need to meet together as one in-person body “are mistaken or insubstantial,” he added, quoting from the Supreme Court’s 2014 Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision.

Then he added this: “It is for the church, not the District or this court, to define for itself the meaning of ‘not forsaking the assembling of ourselves together.’ Nor should the court weigh the relative burden to the church by looking to how easily other religious groups with distinct beliefs have voluntarily changed their worship to accommodate the District’s restrictions.”

Again, in this particular case, “the District has not, as it contends, banned merely one ‘method of worship,’ but instead has foreclosed the church’s only method to exercise its belief in meeting together as a congregation, as its faith requires. Given the District’s restrictions, the church now must choose between violating the law or violating its religious convictions. This constitutes a substantial burden under RFRA.”

One point of confluence between the MacArthur and Dever cases is that both pastors and congregations cited outdoor racial justice protests as comparable to their worship services and claimed unequal treatment.

One point of confluence between the MacArthur and Dever cases is that both pastors and congregations cited outdoor racial justice protests as comparable to their worship services and claimed unequal treatment. In California, the judge found no similarity between the outdoor Black Lives Matter protests populated by socially distanced, masked citizens and the kind of unmasked, un-distanced indoor worship MacArthur was hosting.

In the D.C. case, since Dever and his church were asking for permission to gather outside with more than 100 people — the current D.C. limit — the judge did find some similarity between the church and protesters.

“No matter how the protests were organized and planned, the District’s (and in particular, Mayor Bowser’s) support for at least some mass gatherings undermines its contention that it has a compelling interest in capping the number of attendees at the church’s outdoor services,” Judge McFadden wrote. “The mayor’s apparent encouragement of these protests also implies that the District favors some gatherings (protests) over others (religious services).”

Further — and in complete contrast to MacArthur on the West Coast — the D.C. judge noted that Capitol Hill Baptist “has consistently represented that it will take appropriate precautions such as holding services outdoors, providing for social distancing, and requiring masks. … The District has not put forward sufficient evidence showing that prohibiting a gathering with these precautions is necessary to protect the public.”

MacArthur rallies other pastors

Meanwhile, in California, MacArthur released a nearly 5-minute video on Wednesday, Oct. 7, titled “Church is Essential.” In it, he walks through Grace Community’s empty building while making his case against all government authorities that try to prevent in-person worship as a means of public health protection. He compares his struggle to the Protestant Reformation.

Within four days, the video had been viewed 540,000 times. It was tweeted out by MacArthur and others, including Franklin Graham.

“Today’s current crop of politicians are trampling on the Constitution and on the resolve of citizens to demand their rights under the pressure of a manufactured fear,” MacArthur says in the video.

Then, repeating misinterpreted facts as he has done repeatedly in this battle, he adds: “The reality is that the COVID data doesn’t match the government’s COVID narrative. … . That doesn’t warrant shutting down anything, especially churches … while at the same time leaving open abortion clinics, strip clubs and marijuana dispensaries.” And then: “The health department is on record saying they’re going to allow riots and protests without regard for the mandated safety ordinances.”

His conclusion: “This is obviously targeted discrimination. Leftist and secular government officials have no tolerance for biblical Christianity and are using COVID as an excuse to shut us down. We have to stand firm on the reality that the church is essential.”

In closing, MacArthur issues urgent advice to other pastors: “Open your church. The church is essential.”

The video concludes with a link to a “Church is Essential” petition that is sponsored by the Falkirk Center, a far-right political action group housed at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Va.

Related articles:

Mark Dever says in-person worship is essential to biblical Christianity

Noah had a quick trip compared to John MacArthur’s battle with Los Angeles County

Veteran of Southern Baptist Calvinist ‘reformation’ reflects on success