Many years ago, as a senior in college, I was a member of the cast of our school’s musical theater production of The Music Man. The show had been a sold-out success on Broadway for composer Meredith Willson, and the 1962 movie starring Shirley Jones and Robert Preston won several Academy Awards and a loyal following.

Although I did not portray Harold Hill, the protagonist, I was excited to be in the show — partly because my first and middle name are Robert Preston and I had memorized all the songs. In the spirit of the show, the small college auditorium where we performed nightly was filled with music, laughter, colorful costumes, dancing, marching, trumpet blasts and drum beats.

With Harold and Marian having fallen in love by the final curtain, life looked promising for fatherless and lisping young Winthrop, who had gained self-confidence and the courage to sing because of what the dream of a marching band had done for him. His future life would forever be different because he had come to believe he could march to the distinct, enticing sound of a drum meant just for him.

End of the parade

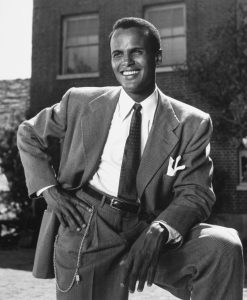

Sadly, the parade has come to an end for singer, actor and activist Harry Belafonte, who died April 25 at the age of 96. Known as an icon in the entertainment industry for introducing calypso music to the United States, he was one of only a few artists to be recognized as an EGOT — winning Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony awards.

Singer Harry Belafonte in his film debut as Mr. Williams, School Principal, in ‘Bright Road’. (Photo by John Swope/Getty Images)

Belafonte was a personal friend and close confidant of Martin Luther King Jr. He put his career on pause to stand with King and to raise money to help fund the Civil Rights movement. He explained his choices in life, which he characterized as marching to his own drum.

Talking with David Muir of ABC News, Belafonte — born in Harlem but deeply influenced by his grandmother in Jamaica — said:

“March to a drumbeat that you believe in.”

I’ve no problem with being thrust into the world of stardom because I never thought about it. …. Nowhere in my boyhood dreams was there the idea that one day I would be in Hollywood, one day I would be on Broadway, or one day I would be making an album that would be successful. Stardom — public responses — was a coincidence to something else. I’ve always been opposed to injustice, having been a victim of it. I have always been for women’s rights, primarily because I saw it happen to my mother as a domestic, and what happened to her as a woman. I’ve always been for people coming together, because I think a world … not integrated is a world disintegrated, with war and pain. I don’t know that I really have all the answers. All that I know is “unto thine own self be true.” March to a drumbeat that you believe in.

“March to a drumbeat that you believe in.” This advice can alter the steps, guide the journey and make the music of one’s soul both meaningful and joyful.

Gandhi’s grandson

Exactly one week after Belafonte’s passing, on May 2, another giant died — international peace icon Arun Manilai Gandhi, the 89-year-old grandson of Mahatma Gandhi.

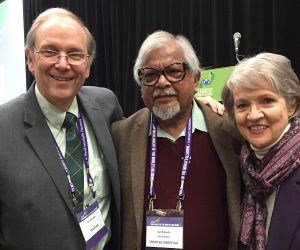

Arun and I were good friends, ever since we served a decade ago as fellow trustees of The Parliament of the World’s Religions. We often shared good conversation over breakfast when we met periodically in Chicago for board meetings of the Parliament. A few years later, I invited Arun to come to Hardin-Simmons University, where I was on the faculty, and to First Baptist Church of Abilene, Texas, to speak. For two days, he touched the hearts and minds of everyone who heard him. It was a wonderful opportunity for Janie and me to nurture our friendship with Arun. I loved and learned from this remarkable Hindu man.

He was born in 1934 in Durban, South Africa, and spent much of his adult life on the Indian subcontinent working as a journalist for The Times of India, as well as promoting social and economic changes for the poor and the oppressed classes of that nation. The sense of justice that later energized Arun and guided his journey began to be formed when he was a boy living with his parents and younger sister in Durban.

In the most famous of his 11 books, Legacy of Love: My Education in the Path of Nonviolence, Arun explains:

In the South Africa of the 1930s and 1940s, overt hate and prejudice were still an integral part of a nonwhite person’s everyday life. How intensely one was insulted depended upon the shade of one person’s skin and the depth of the other person’s prejudice. ….

“While the ordeal lasted only a few minutes, the scars will remain forever.”

When I was 10 years old, three white teenagers approached me one Saturday afternoon, insulted me and beat me up, apparently for some racist satisfaction. I was punched, kicked, laughed at and called names, then left bleeding on the sidewalk. While the ordeal lasted only a few minutes, the scars will remain forever. I vividly remember stumbling to my feet and running home in fear, crying and angry.

I had barely recovered from this humiliating experience when, a few months later, I again became the victim of prejudice and hate, and was beaten up by a gang of black African youths in Durban. It is now more than (69) years since these incidents, but I can still see the hate-filled eyes of the young men and feel the pain and anguish of every blow.

Enduring abuse and beatings for being neither white nor Black enough formed a dark place in Arun’s heart. By the time he was 12 years old, his anger and desire for revenge had become very noticeable to his parents. He was obsessed with exercising to increase his physical stature and strength, so if he ever was assaulted again he could retaliate swiftly, with an equal measure of violence.

Arun Manilai Gandhi

But Manilal and Sushila were wise parents. Desiring to see their son develop a passion for nonviolence, they decided to take him to India to live at Sevagram Ashram with his grandfather, the renowned Mohandas K. Ghandi. So in 1946, Arun embarked upon a transformative period of his life — 18 months spent in the company of a man who was at once both his gentle and affectionate Bapu, and also the “Mahatma,” or “Great Soul,” a man revered by millions of simple and impoverished Indians as well as by scholars, leaders and humanitarians from around the world.

About this formative time of his young life, Arun wrote:

Grandfather was aware of the racist attacks I had suffered in South Africa and the rage they had generated. He knew he had to speak to me about channeling my anger into positive action, but he waited for an appropriate occasion.

He did not have to wait long. One day, upset by the behavior of another child as we played together, I went to Grandfather in tears. Seeing that an opportunity had come, he set his work aside to teach me what I still regard as the most important lesson I have ever learned: how to understand anger and use it wisely.

“Now is the time for you to learn to listen and to cooperate.”

“Now is the time for you to learn to listen and to cooperate,” Grandfather said. “There will always be another point of view besides our own — sometimes right, sometimes wrong — and we must develop the capacity to pause calmly and evaluate. Then we can take a stand that is not aggressive, but conducive to bringing about awareness and change.

We must also cultivate the humility to acknowledge when we are mistaken, just as we expect others to acknowledge their own mistakes. When anger takes control of our minds, we become violent, shouting irrationally at each other, or worse. In these outbursts the casualty is Truth. The ability to respond to anger nonviolently will come to you through constant practice. Do not be domineering, always be faithful and just. Remember that being humble does not mean giving in and allowing yourself to be bullied. Humility means giving respect. You will have respect in return to the extent that you give it to others.”

It was during those months Arun was living at Sevagram Ashram that the campaign of nonviolent resistance against the British Empire was becoming most intense. He was able to witness the ways in which his grandfather was attacked — in the newspapers, the public square and the highest courts of the British viceroy — but he saw that his Bapu never fought back with violence nor was he motivated by revenge.

Lessons shared

Arun was just 13 in January 1948 when his gentle, humble and peaceful grandfather, who was greeting the crowds as he walked to afternoon prayers, was murdered by a lone assassin.

The time he spent with his grandfather made an indelible mark on the heart, mind and soul of Arun Gandhi. He spent much of his adult life proclaiming the message of nonviolence and peaceful resistance, most intentionally through the M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence, which now resides at the University of Rochester in New York.

He crisscrossed the world, speaking to hundreds of thousands of high school and university students about nonviolence. He participated in numerous Renaissance Weekend deliberations on peacemaking with President Clinton and other well-respected Rhodes Scholars from Oxford University.

His life’s work promoting what his grandfather taught him — to pause calmly when challenged, to evaluate alternative responses, to adopt a non-aggressive posture, to cultivate humility and to practice constantly the better ways to defuse explosive anger — are lessons that have been memorialized in countless articles, books and documentary films about Arun Gandhi and his famous mentor. They are a remedy to the political divisiveness and growing interpersonal hatred in America today.

The achievements of Arun and his beloved late wife, Sunanda, all can be traced, in some way, to those instructive days at Sevagram. The formation of their economic initiative, the Center for Social Unity — which helped to alleviate poverty and caste discrimination in more than 300 Indian villages — reflects the egalitarian philosophy of the ashrams or “spiritual communities” like Sevagram, where “hundreds of people came together to live in cooperation” and “everything was done in common, … designed to break down taboos and prejudices and inculcate in the participants a new sense of respect for and understanding of others.”

Along with Sunanda, he rescued 128 orphaned and abandoned children from the streets and placed them in loving homes around the world, a charitable act directly linked to the inspiration of Arun’s grandfather, who loved and took in an angry “lost” grandchild.

Similarly, the Gandhi Worldwide Education Institute, whose goal is to build basic-level schools for the very poorest children of the world, is inspired by the Mahatma’s vision of ashram schools. In addition to receiving an education, the children get fresh vegetables, fruit and milk daily, and their families are taught organic farming techniques. Artisans from nearby communities also teach traditional arts and crafts as a way of helping the children plan their futures.

“These tours are unique because they do not guide participants to ;places of tourist interest but to places of human interest.”

Finally, the Gandhi Legacy Tours that Arun has led each year with his son Tushar celebrate the heritage of his grandfather. According to the Mahatma’s grandson and great grandson, these tours are unique because they do not guide participants to “places of tourist interest but to places of human interest.”

Arun Gandhi has embodied many of his grandfather’s wisest teachings in his own life. Chief among them, perhaps, is the cryptic statement, “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.” As a boy who once wanted an eye-for-an-eye payback in his racist neighborhood in Durban, South Africa, he was able to look back, even from the vantage point of 89 years, to say with confidence that nonviolence is the real pathway to change.

Rob Sellers, Arun Manilai Gandhi and Janie Sellers

“Mahatma” is an honorific title attributed to Arun’s grandfather that means “Great Soul.” No doubt, when his grandfather sat on the ground behind the spinning wheel and talked in a soft voice with his 12-year-old grandson, he had hopes and dreams concerning what Arun could become. How proud would the Mahatma be to have seen the significant life’s work of a boy who marched to a drumbeat that had captured his imagination.

These two icons, Arun Gandhi and Harry Belafonte, left this life in the space of just seven days, and they shared in common a commitment to justice and a determination to march to the sound of the different drum beating in their hearts.

So, I must ask myself, “What is the drumbeat to which I am marching? “What cause stimulates my mind, makes my heart beat faster, stirs my soul? There will be no big parade with 76 trombones and a row of drummers heralding my life when I have breathed my last.

Hopefully, however, people might eulogize me with words like these: “Rob was not afraid to be his own person. He was not a minister who fit the mold, nor the sort of professor who taught his students exactly what they expected to hear. He stressed the testimony of one’s life and actions more than verbal witness. Rob was serious about his faith but also about interfaith relations. His choices, as he lived alongside his beloved wife, were creative and courageous. He certainly ‘marched to a drumbeat that he believed in.’”

May that hope I harbor be reflected in the remaining years of my life.

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is a past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.