Each time a new baby was born, a single red rosebud was placed on the altar in the sanctuary of my home church. My youngest child was born after I returned to serve there, and 12 years ago, her red rosebud graced the altar as the church family rejoiced in her birth. I named this third child Jillian Eden with the hope of the rose from the garden that will one day again bloom in the wilderness.

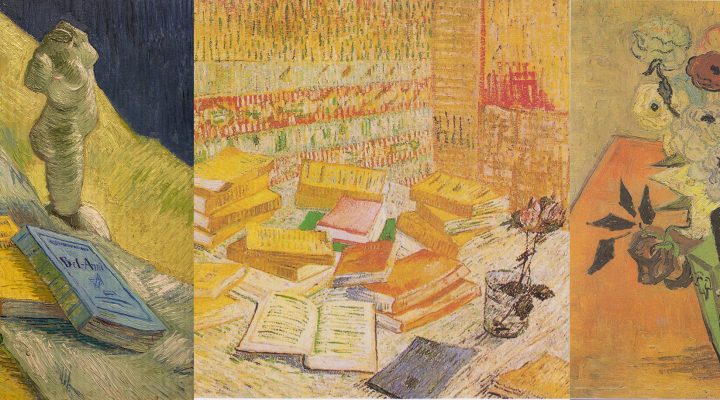

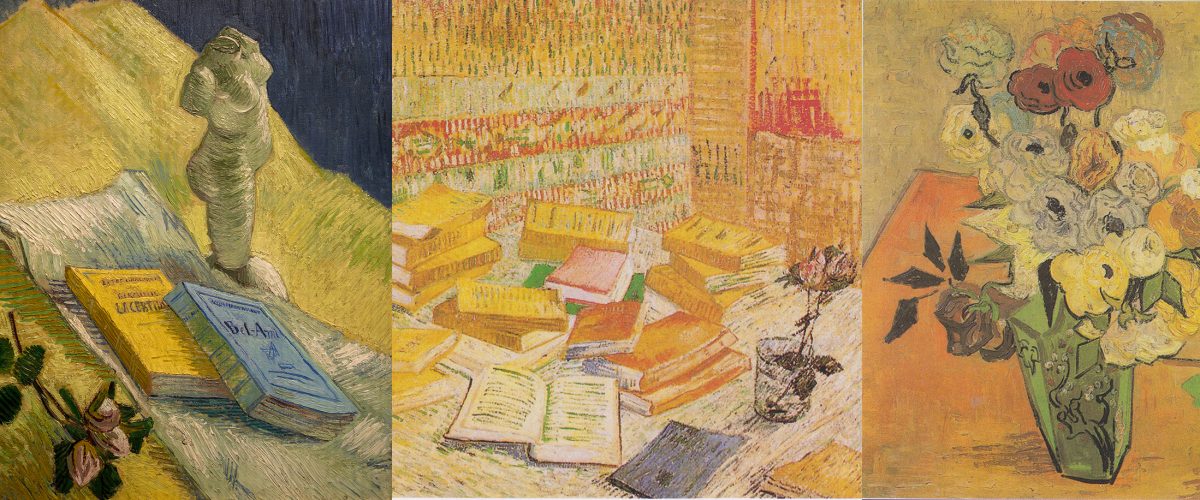

Roses are the appropriate flower of Advent, opposed to the more popular poinsettias, a Christmas flower from South America, which tends to adorn our sanctuaries during the season. Roses have been around for a very long time, long before the birth of the Christ Child.

Roses are the more truthful flower, I think. More fully present, hopeful in the already and not yet of Advent. Roses acknowledge waiting for a pregnancy to come to term is hard, the coming birth is painful and risky. We long for the joy of holding our child in our arms, yet the fear of what might come with birth looms. Sometimes life ends too soon.

Roses in their sorrowful charm acknowledge our achingly beautiful lives, which begin with birth and end in death. We throw roses onto the caskets of our loved ones and dear friends before the dirt covers their graves. We place roses on the headstones of long-lost ancestors. Roses accept our tears.

The single rosebud on the altar recognizing the birth of a child is celebratory, yes. Yet the bud represents hope of fragile new life. Life that may be painful mixed with tears of joy.

Roses are buds that bloom encompassing complexity.

Roses are the flower that represent Mary, the mother of Jesus. The poet Dante says, “Why are you so fascinated with my face that you do not turn and look at the beautiful garden flourishing under the sun of Christ! There is the rose in which the divine word became flesh, and the scent of lilies that enable men to find the right path.”

She blooms as she accepts in herself the invitation to participate in God’s glory. She is blessed as she joins her body with God’s own. She is God’s own beloved, the rose of Sharon. The bud of hope that blooms in the desert, grows among brambles and thorns. She is Mary.

Long ago roses, this ancient flower, were made into circlets to honor the goddesses. These circles of roses later came to be associated with this human woman who was honored and praised, the mother of God. Later rosaries — meaning crown of rose — were made with beads with which to pray. Some have noticed the circle of the rosary beads with the symbol of the cross added to the beads is identical to the symbol of female, of woman.

While Baptists do not utilize a rosary to pray, many forms of our Christian faith and others utilize beads to focus thoughts into prayer. My Baptist heart would not be against any form of prayer or icon (Baptists would use symbol vernacular) that points us to God, for I understand I am my own priest; I have soul freedom to travel my own heart pathways through the Holy Spirit at work in me.

Mary calls to me. I cannot ignore her. She invites me to put my feet on the bare earth. To feel the sun on my bare skin. To close my eyes and drift in peaceful silence, listening for new life to emerge.

HAIL MARY, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

The first phrase is from Luke 1:28, the words of the angel Gabriel greeting Mary with favor and then Luke 1:42 with Elizabeth’s prophetic greeting.

Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us, now and at the hour of our death.

These words are not found in the Gospels or anywhere in Scripture. They are words unfamiliar to my Baptist ears. Foreign and unthinkable to ask for her favor.

Manuscript Leaf with the Pieta, from a Book of Hours (last quarter of 15th century). Mother Mary holds the lifeless Jesus in her arms while Mary the Magdalene looks on with hands folded in prayer.

As a mother, yes, I can relate. As Queen of the Dead, one of the titles associated with Mary, I am finding myself in less comfortable territory. Yet I am willing to learn from Jesus.

“The salvific seed of woman did not reject women, refusing to be served by them. Since he dignified them by his own being made flesh of a woman, he therefore also found them worthy to witness his death. He wanted to begin his life emerging from this sex and to end it in their company,” says Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg, writing in the 17th century.

“Woman born” says scholar Wilda C. Gafney of Jesus. We remember Jesus was the progeny, the child, the seed of Mary only, conceived with the overshadowing of the Holy Spirit.

With her son at the beginning and at the end. Tradition says she held the lifeless body of her son one final time in her arms before Jesus was laid to rest.

The men had fled, the women remained. Author and scholar Jennifer Powell McNutt says in The Mary We Forgot, “God willingly gave himself over to these women, who saw firsthand the surprising and breathtaking expression of God’s power incarnate in those helpless moments of human life: birth and death.”

Woman birthed and woman death-ed. Woman held Jesus, gave him life and comfort, at the beginning and at the end like no one else could. Mary refused to leave her son during his soul piercing death.

We can imagine Mary as our death woman as well. She takes our bodies back into the earth, which is her body, it is her womb; she awaits us in darkness where life will return, reborn.

Like Mary’s, the natural rhythm of my female body reminds me of this cycle of death, renewal and potential for new life. Re-creation begins again with Advent when we are waiting to be born, fresh and new. Each year we cycle through the church year longing for this rebirth to begin again. The birth pains in the darkness are our cue that something new is on its way.

As a pastor to children, I have invited children to gather close together, sitting cross-legged on the floor while helpers covered us up with dark blankets. Once enveloped in the dark and mostly quiet (I try to hush them with a calm and quiet voice), I softly tell the children how Jesus was placed in a cold dark tomb after he was dead and taken down from the Cross. We will wait and listen in the dark.

After a short period of silence, we hear music softly start to play and increase in volume, “Long live God, Prepare ye the way of the Lord!” from the finale of Godspell. A figure dressed as Jesus carrying a lighted candle raises the blankets and beckons us into the light. I prompt the children to shout: “We’re alive! We’re alive!” and we follow Jesus out into the light as the blankets of the tomb are scattered onto the ground. Looking back, this could also be an acting out of birth, the cyclical nature of our lives cannot be ignored.

To be alive is to be certain to die. Our living will not be without pain, nor will it be without joy. Creative acceptance of this pain is how we can be led to resurrection. Mary is our grief teacher. Her sorrow for her child is a part of her growth and divine partnership, co-creating with God.

It is crucial to understand Mary’s whole life as monumental. Wholeness with God already was in her possession, why she was chosen, why she was able to co-create with the divine.

Birthing Jesus was only one part of the mission of an art of living in love.

We act out the story of Mary in our own lives like the children and I acted out the story of Jesus in the tomb. Its familiarity helps us to be incarnational people. At least it should make us so, Sue Monk Kidd says. We could “become participants of the divine nature,” as in 2 Peter 1:4.

For each of us is Mary.

The darkness of the tomb brings us full circle. We must wait in darkness, in grief for new life to emerge.

The womb is readying. Then a rosebud.

May Christ be born in you.

Julia Goldie Day is an ordained minister within the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in Memphis, Tenn. She is a painter and proud mother to Jasper, Barak and Jillian. Learn more at her website or follow her on socials @JuliaGoldieDay.

Further resources inspired by themes from “Mary the Rosebud” will be provided by the author at juliagoldieday.comeach week. Click for poetry, prayers, music and more art to inspire you this season of Advent.