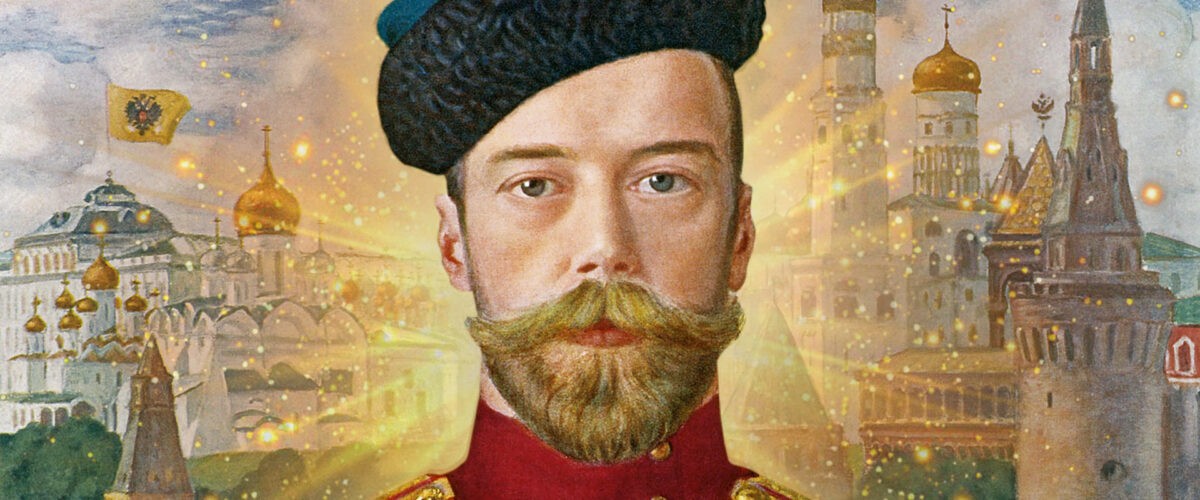

Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked attack on Ukraine has surprised some Western observers who previously considered the Russian president to be a pragmatic realist, even if an authoritarian one, said a Mercer University professor of Russian and Soviet history.

“I never considered him a riverboat gambler but one who prizes order and one who prizes stability. That is obviously not the case,” said Wallace Daniel, distinguished professor of history at Mercer. He spoke during a March 3 in-person event that also was livestreamed. “He is taking an enormous risk. If he succeeds, if he wins, if he weathers this storm, it will come at a great cost to people there and elsewhere.”

Wallace Daniel

Wallace was one of three Mercer faculty members with expertise on the two warring nations to speak during “Perspectives on the Russia/Ukraine Conflict,” hosted by the Macon, Ga., university’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The presentation covered the historical relationship between Russia and Ukraine, the possible psychological and religious motives driving Putin’s action, and the potential long-term social, economic and political impact of the ongoing invasion launched Feb. 24.

There are numerous potential outcomes, and many of them are chilling, Daniel said.

“If (Putin) loses, if the Russian people fail to back him, it will eventually lead to his end and the end of his regime. Personally, I hope this latter will prevail, but the stakes could not be higher. It is the conflict between an authoritarian and a democratic society, and between an authoritarian world and a democratic world. We see the same conflict here in the United States between those two forces.”

As Putin-style authoritarianism is sweeping the globe, it also has caught on among many Republicans who, along with former President Donald Trump, have expressed praise for the dictator and his invasion.

“The Russian-Ukrainian conflict brings this right to our doorstep,” Daniel said.

“The Russian-Ukrainian conflict brings this right to our doorstep.”

The invasion has several purposes, he added, including making Russia a world power, seeking retribution for the 2014 uprising against Ukraine’s then-Russian friendly government, and eliminating a large, pro-Western democracy along the Russian border.

The military operation also serves to counter Ukraine’s early 1990s decision to split from Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a move that tapped into the ancient, and often antagonistic, relationship between the two countries, Daniel said.

“Ukrainians are an unruly, freedom-loving people. You can see it in their literature. You can see it in their music. You can see in their famous Cossack dancers,” he explained. “Two of the greatest rebellions in Russian history began in Ukraine.”

Russian anger was further stoked in recent years when 7,000 of 19,000 Orthodox churches in the Ukraine traded oversight by Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill for that offered by the head of the Greek Orthodox Church.

“Putin and Kirill hated that,” Daniel said.

Chris Grant

But the gap between Ukraine and Russia widened in 2014 when Putin sent occupation forces into Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, said Chris Grant, a Mercer political science professor.

Putin claimed the move was to ensure the freedom and safety of Russian-speaking people in the eastern part of Ukraine, which was ironic because many Ukrainians until then were emersed in Russian and Ukrainian culture and language and did not have hostile attitudes toward residents of the Crimea, Grant said by video link from Poland after evacuating Ukraine as a Fulbright scholar.

Putin’s recent claims that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is promoting anti-Russian sentiments and Naziism are just as ironic because Zelenskyy is Jewish and known to favor speaking Russian to Ukrainian. “It’s fantastical,” he said.

Ukrainian women are fighting — and dying — alongside men in the military as a sign of the national solidarity of the nation under attack.

“Their deaths are happening because a tyrannical dictator in 2022 has decided to build an empire back … and he’s creating orphans, widows and widowers,” Grant said. “And he’s going to take on people with guns and Molotov cocktails with fire-shooting canons and missiles and tanks in the modern world, in our society, in the world in which we live. And to me, that is stunning.”

Grant said he had misjudged Putin prior to the invasion to be more calculated in his actions. Now that war has broken out, he realizes it’s “all because Vladimir Putin envisions himself as some sort of Russian czar.”

James Hunt

James Hunt, professor of law and business at Mercer, traced the tension to Ukraine’s emergence from communism, which left the nation with a legal system consisting of unfair and unpredictable laws administered by cronyism and corrupt judges.

Hunt, who was a Fulbright scholar in Ukraine from 2005 to 2006, recalled encountering law students and lawyers attempting to push back against Soviet-style justice. And the work continues, he said. “Ukrainians have been trying to overcome this deep-seated corruption and lack of a civil society that was left to them by the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

He recalled meeting economics students and others who dreamed of creating a Ukrainian economy that would provide decent health care and wages. And he recalled religious minorities to be equally determined and brave. “In the U.S., we take freedom of religion for granted. People we met at church in Kyiv … were coming out of a system that didn’t believe in freedom of religion.”

Such efforts are nothing short of heroic, he said. “It is seen as radical because it was a rejection of a kind of legal system and a kind of economic system that, I’m afraid to say, Vladimir Putin still stands for. He doesn’t stand for the rule of law, he doesn’t stand for an open-market economy.”

While it’s hard to discern what the Russian president expects from his invasion of Ukraine, it’s clearly not a rational economic system, Hunt said.

“Putin is willing to pay an enormous amount of money (for the invasion). I can’t imagine how much it’s already cost. Billions, just in the last week. Is he willing to accept $1 trillion? $2 trillion? $3 trillion? I don’t know the answer to that, and I don’t think anybody does. His behavior … suggests he’s willing to throw the dice altogether with this. And that means it’s going to be a very expensive war, especially for the Russian and Ukrainian people.”

Related articles:

The post-Cold War ‘peace’ is dead; long live the struggle for liberal democracy | Analysis by Erich Bridges

Religious liberty in Ukraine is ‘doomed’ if Russian invasion succeeds

Let’s be clear: Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is not about the rapture and Russia in biblical prophecy | Analysis by Rodney Kennedy

Don’t forget the religious implications of geopolitical upheaval | Analysis by Richard Wilson