The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 was deadly but not altogether noteworthy to many Baptists, historians say.

In fact, those who earn a living combing through denominational newspaper archives and associational records say they are astonished how little attention churches, state and national faith groups paid the disease that killed an estimated 50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States.

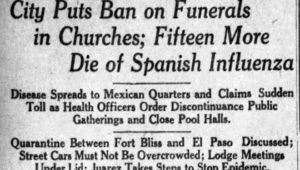

Secular as well as Baptist publications tended to under-report the outbreak.

“Buckner Children’s Home had over 200 cases of the flu among the kids, and that wasn’t a huge news story then,” said Alan Lefever, director of the Texas Baptist Historical Collection. “Could you imagine if, today, a children’s home had 200 cases of COVID? That would be on every TV station.”

“Buckner Children’s Home had over 200 cases of the flu among the kids, and that wasn’t a huge news story then,” said Alan Lefever, director of the Texas Baptist Historical Collection. “Could you imagine if, today, a children’s home had 200 cases of COVID? That would be on every TV station.”

Another major difference between the Spanish flu and COVID-19 pandemics is the absence of churches protesting government-mandated shutdowns.

“At least here in Rhode Island, they did what the government said to do. Everybody wore masks and they social distanced themselves,” said James Lemons, a historian, author and clerk of the First Baptist Church in America in Providence, R.I.

Lefever said he found similar evidence about congregations in Dallas and Houston. “In those areas, the churches stopped meeting because local city officials asked them to.”

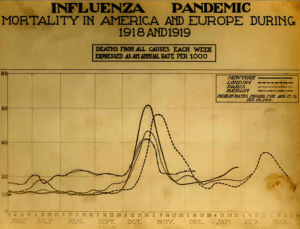

Lefever, Lemons and other Baptist historians say the Spanish flu pandemic, which ravaged the nation in 1918 and 1919, reveals much about people of faith and Americans in general during that period. Their research speaks volumes, even when it is silent on topics that would be headline news in 2020.

Playing down a pandemic

Lefever said he finds the absence of detailed pandemic information in church and denominational records “shocking.”

When schools and churches were closed in the fall of 1918, faith-based hospitals were filled to capacity and the Baptist General Convention of Texas was forced to reschedule its annual meeting from November to December.

“There is no mention of it in the associational minutes,” he reported. “There is no mention of the pandemic.”

Headline from the Oct. 9, 1918, El Paso Times.

The tendency wasn’t limited to Texas or to Baptists, for that matter.

“I have found little systematic work done regarding religion and the 1918 pandemic in America,” Baptist author and historian Bruce Gourley said.

The country as a whole seemed to downplay the Spanish flu, he added. “Many Americans just put it (the pandemic) behind them in focusing on better times.”

There were other major developments competing for their attention, Lemons explained, and World War I was chief among them.

The first full year of the pandemic coincided with the final months of the war when American involvement was at its highest. The war ended in November 1918, which kept it in the American consciousness.

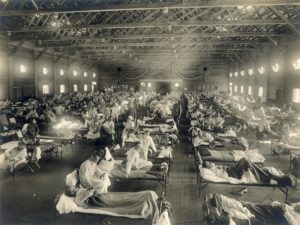

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston. (Photo: Common domain)

The “War to End All Wars” also played a part in stoking the pandemic. Flu outbreaks were rampant in military camps in Europe in the final months of hostilities, and soldiers brought the disease home with them. “It’s a recognized fact that Spanish flu killed more soldiers than the war did,” Lemons said.

The Spanish flu targeted a much wider age range than COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the highest mortality rates occurred among those under 5 years old, those 20 to 40 years old and those 65 and older. COVID-19, by comparison, has disproportionately killed older adults and persons of color.

In addition to the war, there was the contentious issue of alcohol, Lemons added. “The nation was caught up with the debate over Prohibition, which was ratified in 1919.”

This may all explain why detail is so often lacking when churches reported to their regional and state groups about the loss of members. “Very rarely did anyone give a cause of death,” Lemons said.

‘No evidence that it was politicized’

Churches were much more likely to share concerns about the pandemic’s impact on evangelism. There are expressions of dismay over the postponement of a Billy Sunday revival scheduled for the fall in Providence, Lemons said.

Evangelist Billy Sunday speaks with Mrs. George Pullman in Chicago, 1918. From March 10 to May 28 of that year, Sunday held a series of revivals in Chicago. The first cases of Spanish flu were reported at Fort Riley, Kansas, about the same time. That fall, the evangelist moved his tabernacle to Providence, R.I., where he held 70 public meetings in September and October. He urged congregants to “pray down” both the flu and “the Hun,” and newspapers reported numbers of people collapsing in the aisles. The Providence Aldermen shut down public gatherings in October, and Sunday complied. “It is up to us to hope and pray. We are always willing to help anything that is for the public good and do it cheerfully. There is nothing drastic in the order, and it is issued in an attempt to stamp out this epidemic,” he said. (Photo: Presbyterian Historical Society)

One congregation lamented the impact of the shut-down on its mission. “The winter is the time of spiritual harvest, but last year was a year of hardship with us, on account of the prevailing epidemic, and the severity of the winter,” the Rhode Island congregation reported in a document provided by Lemons.

Yet they closed as directed — a practice shared by the larger community. “In some places you couldn’t get on a trolley car without a mask on,” he said.

People understood civic responsibility and knew what it meant to be safe and sensible, Lemons added. “It discredits Christians when churches meet and say, ‘Jesus is my vaccine.’”

In Texas, congregations also seemed to understand why they needed to close.

“When they issued stay-at-home orders for churches and schools, they knew it was part of an effort to flatten the curve,” Lefever said. “And these people in 1918 were worshiping in their homes.”

He found no evidence of protest or defiance of those orders. “There is nothing about churches responding negatively to the request because they didn’t see it as an infringement on their religious freedom. They saw it as their responsibility.”

Nor was there any documentation to suggest the divisiveness that has come to define the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S.

“I see no evidence that it was politicized,” Lefever said. “And it’s amazed me that conservative Baptists made this a religious liberty issue this time around whereas no one said that in 1918.”

Instead, Christians a century ago saw in the pandemic as an opportunity to serve. “One of the ways Baptists poured resources into the pandemic, even though its’s not recorded, was into these hospitals they had created,” Lefever explained.

Church historian Bill Leonard said he has a photo of E.Y. Mullins, then president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., that defines Baptist service during the Spanish flu pandemic.

“He’s dressed in an army uniform having just come from Fort Knox, where he was chaplain to soldiers during the pandemic. He’s haggard looking, exhausted and obviously disturbed,” Leonard said.

“So, my takeaway from that is that Baptist ministers did chaplaincy work where needed in hospitals, army bases, jails, etc., much as now.”

Related articles:

How John MacArthur loves the Bible but not his neighbor

Don’t expect churches to return to ‘normal’ after pandemic

Q&A with John Finley on preserving Baptist history amid COVID-19