A former Baptist executive who claims he was defamed by the leaders of a Southern Baptist Convention agency now says Baptists concerned about the fraudulent resume of Willie McLaurin should be more concerned about false witness offered under oath by leaders of the SBC North American Mission Board.

Will McRaney’s case against NAMB and its president, Kevin Ezell, recently was dismissed by a federal judge who said secular courts cannot intervene in ecclesial matters. McRaney is still considering whether to appeal that ruling, which he believes misinterprets and threatens Baptist polity.

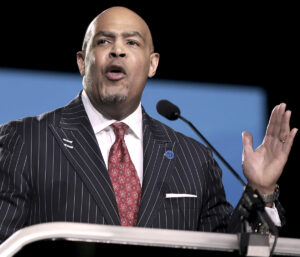

In the meantime, attention has turned to the SBC Executive Committee in Nashville, where Interim President Willie McLaurin stepped down abruptly Aug. 18 when most of his resume was exposed as lies — from education to military service.

Willie McLaurin

It is right for the Executive Committee to have launched an internal investigation into McLaurin’s deception, said McRaney, former executive director of the Baptist Convention of Maryland and Delaware. But what NAMB and Ezell did in his own case is “remarkably worse than what Willie did or could have done.”

McLaurin spoke for himself in his deception, but Ezell and NAMB represented millions of Southern Baptists in their official roles and the court testimony they have given, McRaney said. Who will investigate NAMB?, he asked.

Similar requests have been from various people — even on the floor of an SBC annual meeting — but have been routinely rebuffed or referred to NAMB’s trustee board, which has oversight of the agency and its president.

Problematic amicus brief

At issue is testimony given in McRaney’s long-running case and an earlier amicus brief filed by the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission when one aspect of the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

At issue is testimony given in McRaney’s long-running case and an earlier amicus brief filed by the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

The ERLC, working with the conservative legal group Thomas More Society, filed an amicus brief stating the SBC is a “hierarchy” and “umbrella organization” wherein state conventions are accountable to its national entities. The ERLC later amended that brief, after its publication created a firestorm of protest within the denomination.

According to traditional Baptist polity, all denominational entities and churches are autonomous and none has authority over any other — unlike connectional religious bodies such as the Roman Catholic Church or The United Methodist Church.

This understanding was pivotal to McRaney’s case, because he claimed Ezell and NAMB had no ecclesial standing to force his firing from the state convention and therefore could be held liable for defaming him. If he had been a Roman Catholic bishop fired by an archbishop, that would have been different.

Kevin Ezell

Before McRaney’s case was dismissed — based on one judge’s ruling that his termination fell within the internal workings of a single “church” — hours of testimony were given in depositions. Those depositions have not been sealed.

In one, Ezell testifies that he had no involvement in drafting or reviewing the problematic amicus brief. McRaney charges that is not true, and that Ezell and NAMB actually originated the brief and knew exactly what it said.

In an email to BNG, McRaney said NAMB “(1) initiated the amicus brief filed by ERLC, (2) provided sample amicus briefs from another case, (3) saw the draft before it was filed, and (4) obviously they learned of its filing but did not correct it in the courts.”

McRaney’s assertion is based on testimony given in preparation for the trial that has not happened, including a Privilege Log from Thomas More Society that appears to indicate a NAMB attorney was involved in drafting and reviewing the controversial brief.

Ezell maintains that even though he is the president of NAMB he does not read legal documents because he “trust(s) the lawyers.”

Throughout his deposition, Ezell maintains that even though he is the president of NAMB he does not read legal documents because he “trust(s) the lawyers.”

Whatever Ezell’s role was or was not, people working for him were involved in drafting and reviewing the amicus brief, McRaney charges, even though the ERLC and its then-president, Russell Moore, took the blame for it.

Portraying NAMB and the BCMD as connected — as that amicus brief wrongly did — was important to NAMB’s defense against McRaney’s defamation suit, he said.

Neither Ezell nor NAMB’s designated media spokesman, Mike Ebert, routinely answer inquiries from BNG or any other news outlets. They have had no public comment on any of these legal proceedings.

Chairman’s letter to SBC leaders

However, one additional piece of evidence submitted in the discovery phase of the trial is a letter written on NAMB letterhead from Danny de Armas, chairman of NAMB’s board of trustees, to “SBC Ministry Leaders.” It is dated Dec. 15, 2020, just weeks before NAMB appealed to the Supreme Court to stop the McRaney case on the grounds of it being purely an internal church matter.

The Supreme Court later denied that request.

Danny de Armas

De Armas told other SBC leaders: “NAMB wants to make sure the federal courts fully explore the religious liberty protections afforded all churches and ministries by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. … Because appeals to the Supreme Court are rarely granted, we want to openly communicate with you about our reasons for this effort and about the risks to your ministries should our effort be unsuccessful.”

He cites the Baptist doctrine of autonomy and says: “We all know that the local church is the controlling entity in the SBC and will always remain so. Similarly, we all know that local churches, local pastors, local associations, state conventions, and national entities should be free to make ministry decisions free of government oversight and interference. When ministry disagreements do arise, those disputes need to be resolved biblically, not by secular courts. This lawsuit filed against NAMB poses a very real risk to the autonomy and freedom we all enjoy. As soon as we allow the government to dictate what we do and how we do it, we all lose our ability to freely share the gospel and execute our ministry strategy without interference from the government.”

“When ministry disagreements do arise, those disputes need to be resolved biblically, not by secular courts.”

What he does not say about autonomy is the corollary belief that the national denomination cannot dictate to a state convention what it must do — the heart of McRaney’s case.

Instead, de Armas portrays NAMB’s defense as being “about protecting our ability — and your ability — to freely exercise our religious faith and ministerial decision-making.”

The chairman acknowledges “there will be some who suggest that NAMB simply does not want to face the claims in the lawsuit. Nothing could be further from the truth. However, this case is far bigger than NAMB or one person’s claims. It is about protecting our churches and pastors from intrusive government interference into our polity and practices. It’s about standing up for the religious freedoms we enjoy as Americans, as followers of Jesus, as Southern Baptists, and as pastors.”

Will McRaney

McRaney contends this explanation further denies the reality of the claims made in the case, which were not about government intrusion into religious affairs.

Now that a federal judge has ruled in NAMB’s favor and dismissed McRaney’s case — on the grounds that the entire thing is related to a single “church” matter — McRaney continues to warn this redefinition of Baptist polity is the real danger.

“The next major attack that is being prepared for the courts will be over SBC autonomy. That is the target,” he said in an email to BNG. “Baptist autonomy in the courts is at stake. Baptist leaders cannot afford to be silent, unclear or let deception on Baptists stand unchallenged.”

Related articles:

McRaney warns dismissal of his case against NAMB raises urgent threat to Baptist autonomy

U.S. district judge dismisses McRaney’s case against NAMB

SBC agency’s appeal to Supreme Court touches on religious liberty, defamation and Baptist autonomy

Southern Baptist polity on trial in lawsuit appeal

What’s old is new again: Conservatives threaten funding over SBC’s ethics agency

Seven years later, Will McRaney might get his day in court against NAMB — maybe