Wake Forest College was founded by North Carolina Baptists in the town of Wake Forest in 1834. The Reverend Samuel Wait, the school’s first president, was a slaveholder, as were his three successors, including the Reverend Washington Manly Wingate, the fourth president.

On May 7, 2021, Nathan Hatch, the 13th president of what is now Wake Forest University, a non-sectarian private school in Winston-Salem, announced that trustees had approved removing Wingate’s name from Wingate Hall, a facility connected to Wait Chapel, a grand assembly space that will retain the name of the founding president. Wingate Hall will be renamed “May 7, 1860 Hall” in memory of the 16 slaves bequeathed to Wake Forest College from the estate of Baptist layman John Blount and sold on that day, with Wingate’s approval.

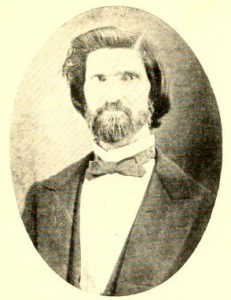

Bill Leonard

The names of those 16 human beings were listed as Isaac, Jim, Lucy, Caroline, Pompie, Emma, Nancy, Harriet and child, Joseph, Harry, Ann and two children, Thomas, and Mary. Mary fled slavery only to be captured in Norfolk, Va., and sold. The $10,718 obtained from the sale of these 16 humans kept Wake Forest College afloat on the edge of the Civil War.

Hatch explained: “By renaming this building, we acknowledge the university’s participation in slavery, recognize this aspect of our history and remember those who labored at the institution against their will. We hear their stories, learn their names and honor what they endured for our institution.”

He noted that while renaming Wingate Hall, the school “will keep the name of Wait Chapel to underscore the complexity of our story. In leaving the Wait name on the chapel that shares a foundation with the newly named May 7, 1860 Hall, we acknowledge the inherent contradictions that summon our intellect and moral conviction. The complexity and contradictions create a tension that invites engagement with our story and the people whose lives are remembered and honored.”

Wingate Hall

As a response to the tensions arising from that institutional history, origins inseparably linked to slave labor, slave owners and Baptist support for both, Hatch reported that the school will “launch a process to create a memorial to affirm the humanity and dignity of those previously not remembered or honored in Wake Forest’s antebellum history. It will offer a context for the record of Samuel Wait as the founder of the university who had enslaved persons serving his household. With the information we have, we will expand the story of our founding to accurately and fully reflect the reality of (Wait’s) establishing an institution to serve humanity even while actively denying some people their own humanity.”

Considerable historical investigation and institutional self-examination preceded this decision, efforts formalized in 2017 when Wake Forest joined the Universities Studying Slavery Consortium, a gathering of schools with slave-related origins. From that connection, the school established the Slavery, Race and Memory Project in 2019, from which came an online volume of essays titled To Stand With and For Humanity: Essays from the Wake Forest Slavery, Race, and Memory Project. In 2019, Hatch formed the President’s Commission on Race, Equity and Inclusion to address issues of racial concern and discrimination, past and present.

I readily participated in these efforts, contributing an essay titled, “Defending the Indefensible: Wake Forest, Baptists, and the Bible” to the online volume. More recently, although now retired from Wake Forest, I was invited to join current religion and divinity school faculty in researching the presidency of Washington Manly Wingate, whose name identified the building occupied by those two academic communities. I benefit from their fine research in much of the biographical and institutional information provided here.

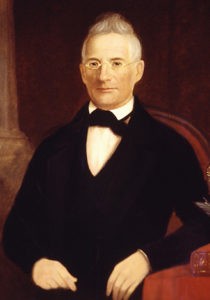

Washington Manly Wingate

Washington Manly Wingate (1828-1879) was born in Darlington, S.C., graduating from Wake Forest College in 1849, then studying for two years (1849-1851) at the Furman Theological Institute, forerunner of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He married Mary E. Webb in 1850, with seven children born of their union. Wingate was ordained to Baptist ministry in 1852, the year he became Wake Forest’s financial agent. In 1853, he was named president of the college and professor of “Moral and Intellectual Philosophy and Rhetoric,” serving until his death in 1879.

Like the presidents before him, Wingate was pastor of Wake Forest Baptist Church. When the school closed, 1862-1866, because of the Civil War, he preached to Confederate soldiers and served as pastor of several Baptist congregations. At his funeral, a Baptist leader declared: “During his long presidency, the moral character of the students of Wake Forest College has been a higher tone than that of any similar institution known to me in America. The crowning glory of the man was his piety.”

Amid the depths of his moral and spiritual sanctity, Washington Manly Wingate was a slave owner. Records from the “List of Members Revised” of the Wake Forest Baptist Church, January 1865, document that among “Colored Males” who were church members was “Wingate’s Isaac.” “Colored Females” included “Wingate’s Hannah,” “Wingate’s Jinnie,” and “Wingate’s Charlotte.”

Their slavery was so all-encompassing that even their membership in the body of Christ was defined by their reverend owner’s name. Pastor Wingate, and the Baptist culture that encompassed him, interpreted the Bible so as to grant pastor and congregation permission to own and spiritually “un-name” their Black Christian brothers and sisters.

Samuel Wait

That is why such historical research and resulting action by Wake Forest University and other schools acknowledging and responding to their slavery-related origins goes beyond memory to the present moment in American life. By removing Wingate’s name from one building and retaining Wait’s name on another, the university is not “canceling culture” but “owning” a culture long ignored and in need of recognition, remedy and yes, repentance. It says where the school has been and must never go again in any form.

Displacing Wingate’s name with the date that human beings were sold at auction to benefit the school’s preservation represents a small but significant step toward memorializing persons previously unnamed and unacknowledged. Retaining Wait’s name in proximity to May 7, 1860 Hall becomes perpetual witness to the moral paradox of Wake Forest’s history.

To apply words from the gender-related research of my spouse, Candyce Crew Leonard, Wake Forest professor emerita, the abolition of Wingate’s name and the retention of Wait’s “serves to collapse the distance between past and present,” reconstituting “the past and the present on the same temporal plane.” The two actions connect to the unsettling racial “inequalities” present in both 19th and 21st centuries.

“By removing Wingate’s name from one building and retaining Wait’s name on another, the university is not ‘canceling culture’ but ‘owning’ a culture long ignored and in need of recognition, remedy and yes, repentance.”

Such actions surely have implications for our current socio-political environment, as when Sen. Mitch McConnell recently responded to The New York Times’ “1619 project,” saying: “There are a lot of exotic notions about what are the most important points in American history. I simply disagree with the notions The New York Times laid out there that the year 1619 was one of those years.” Perhaps the former majority leader and those like him would benefit from their own “Slavery, Race, and Memory Project.”

Personally, the Wingate research hit me hard. I have spent more than 40 years studying the history of Baptists, Black and white, through slavery and abolition, Jim Crow and Civil Rights, along with salvation and damnation aplenty. I taught at both Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and Wake Forest University, two slavery-borne schools with chapels named for slave owners, yet the only two Southern Baptist-related schools to invite Martin Luther King Jr. to preach in those environs.

The catharsis of all that struck me a few weeks ago when I began typing the words “Wingate’s Isaac” on my portion of the Wake Forest report and, without warning, started weeping. When I attempt to recount that moment to Candyce Crew Leonard and a few friends, the tears still well up.

I hope they always will.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

Baylor not yet where it wants to be on race, Livingstone tells forum