Poverty fell steeply among immigrants in the U.S. after the Great Recession and even further during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new report by the Migration Policy Institute.

The study analyzed U.S. Census Bureau data to measure the way economic trends, immigration growth and federal assistance programs helped reduce poverty among immigrants. The report defines immigrants as people who were not American citizens at birth, including refugees, asylees, legal permanent residents and those in the country without authorization.

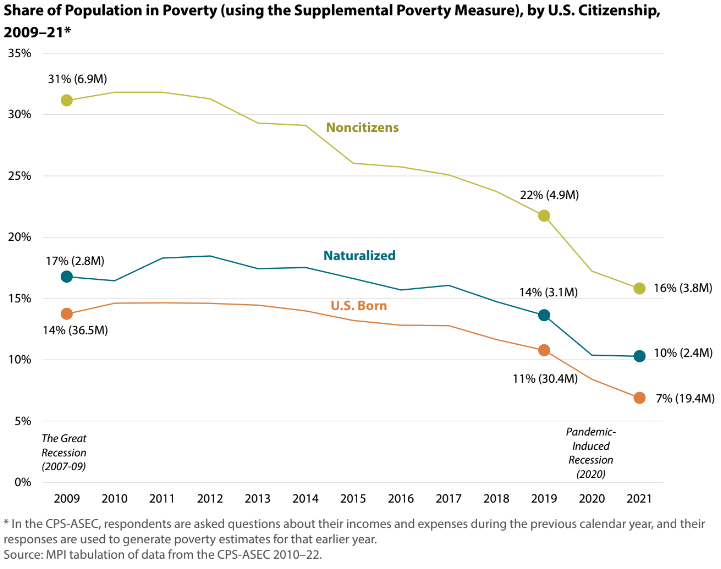

“Despite an increase in the total number of immigrants nationwide over the decade, the number of immigrants experiencing poverty fell from more than 9.6 million in 2009 to slightly less than 8 million in 2019, and the share of immigrants in poverty fell from 25% to 18%.”

The trend continued from 2019 to 2021, with the number of immigrants in the grips of poverty falling from 8 million to 6.1 million, and the rate plummeting from 18% to 13%, MPI reported.

“Behind the 2019–21 declines were massive new and expanded income support and transfer programs that the federal, state and local governments introduced to blunt the economic impacts of the public-health crisis,” the report states. “The pandemic-driven aid programs included three rounds of stimulus payments and expansions of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (also called food stamps), the Child Tax Credit, and unemployment insurance.”

MPI said its analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure found striking declines in poverty among both U.S.-born and immigrant children.

“The number of U.S.-born children with only U.S.-born parents in poor families fell from 7.5 million in 2009 to about 2 million in 2021, a 73% drop,” according to the report. “Over the same period, the number of children of immigrants in poor families fell from 4.6 million to 1.5 million, a 68% decline. Among children in immigrant families, particularly precipitous drops could be seen among U.S.-citizen children with noncitizen parents, whose numbers fell from 2.3 million to 684,000, or by 71%, between 2009 and 2021.”

The trend positively affected immigrants regardless of ethnic or racial identity, the institute added. “For instance, the shares of Latino and Black noncitizens in poverty — historically disadvantaged both because of their minority and noncitizen status — fell by about half between 2009 and 2021.”

The report delved further into the factors behind the downward trend in immigrant poverty.

“In the past decade, the proportion of immigrant adults without a high school education fell, while the share with college degrees rose. Similarly, the share of immigrants who are English proficient increased. The amount of income immigrant families have at their disposal is also likely to have increased because the share of immigrant women in the work force grew, while the average size of immigrant families declined.”

Also contributing to the decline was an increase in the share of immigrants who were naturalized or legal permanent residents — from 58% in 2019 to 73% in 2019. The share of unauthorized immigrants declined from 28% to 23% in that period, the report adds.

“In short, the broad, somewhat surprising declines in poverty across the nation’s immigrant population likely result not only from the stronger social welfare policies and spending in recent years but also from the immigrant population’s changing characteristics and positive immigrant integration trends,” it concludes.

Despite the impressive declines, immigrants continued to suffer poverty at disproportionately high rates in 2021, with 24% overall enduring poverty despite representing only 14% of the U.S. population.

“Noncitizens were more than twice as likely to be poor as their U.S.-born counterparts.”

“Noncitizens were more than twice as likely to be poor as their U.S.-born counterparts (16% versus 7%). And for all citizenship categories (noncitizens, naturalized citizens and U.S.-born citizens), Latino and Black individuals were more likely to experience poverty than either Asian American and Pacific Islander or white individuals. The data also reveal that parental citizenship is highly correlated with poverty: children of immigrants with only noncitizen parents were three to four times more likely to experience poverty than children with one or more U.S.-citizen parents.”

MPI cautioned the gains described in the report could be threatened by ongoing inflation coupled with the phase-out of pandemic-era assistance programs.

“There is already some evidence that poverty may be rising. Between spring and fall of 2021, more U.S. families — particularly those with children and racial/ethnic minorities — reported experiencing difficulties getting enough food, paying their rent or mortgage and covering other household expenses such as auto payments, medical expenses or student loans.”

But an economy with close to 11 million job openings in January 2023, and the ongoing arrival of refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants, may yet help stave off the growth of hunger, MPI said.

“The characteristics of all newcomers — from college-educated tech workers to family green-card recipients to asylum seekers — and their varied levels of socioeconomic mobility will influence overall immigrant poverty levels.”