You may not be able to choose when or how you die, but you have many choices when it comes to taking care of your bodily remains, as new technologies and laws multiply the options and the ethical questions involved.

Laws in some states now allow natural burial, human composting, water cremation and other options, and residents of other states can take advantage of these choices if their remains are transported.

This brave new world of burial alternatives presents new ethical questions that theologians, families and attorneys updating clients’ wills need to understand and address.

Here’s a brief look at both the past and future of last remains.

Ancient rites

From Egypt’s pyramids to Europe’s megalithic tombs to America’s indigenous burial mounds, ancient humans applied their creativity in memorializing their dead, leaving impressive monuments that survive and amaze to this day.

Ancient people of the East and the West went their own ways. Hinduism prescribes the burning, or cremation, of bodies, which are believed to be part of this illusory physical world, or maya. Buddha was cremated, so many disciples have followed his model.

(123rf.com)

Jews and Christians have long practiced burial, in part out of respect for the human body, which is created by God in God’s own image.

Modern changes and debates

Egyptians perfected the art of embalming millennia ago, but the practice wasn’t adopted in the U.S. until the Civil War, when tens of thousands of soldiers’ last remains were transported long distances for burial back home.

The adoption of embalming led to the practice of viewing the deceased person’s body, presented in a state of repose. By the 20th century, embalming and viewing of a body in a funeral home was the chosen means of memorializing the dead for some 95% of Americans.

Americans didn’t adopt cremation until cremation societies popularized the method in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but the greatest acceptance of this method has occurred in the past two decades due to environmental and economic concerns. Today, more than half of Americans choose cremation rather than burial.

Today’s cremation process is a high-energy industrial alternative to the ancient Hindu practice. A body is placed inside a closed furnace (cremator) at a crematorium, where temperatures rise to 1,600 to 1,800 °F.

Many Christian denominations and traditions leave the choice to the individual, but some Christian thinkers have rejected cremation, largely because of the perceived harm it does to the human body.

Russell Moore, for example, counsels Christians to reject cremation in favor of burial, a view long promoted by the Catholic Church. As Moore wrote, “The question is not simply whether cremation is always a personal sin. The question is not whether God can reassemble ‘cremains.’ The question is whether burial is a Christian act and, if so, then what does it communicate?”

Moore’s views on bodily remains spring from his theology of the human body: “For Christians, burial is not the disposal of a thing. It is caring for a person. In burial, we’re reminded that the body is not a shell, a husk tossed aside by the ‘real’ person, the soul within. To be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord (2 Corinthians 5:6–8; Philippians 1:23), but the body that remains still belongs to someone, someone we love, someone who will reclaim it one day.”

The Catholic Church’s 2016 guidelines say cremation is permissible for Catholics, but cremains should rest in a sacred place, such as a church columbarium, not scattered at sea, or kept in the growing number of approaches that use cremains as a means of self-expression. Currently, ashes can be entombed in a coral reef, freeze-dried and shattered, set adrift in an “ice urn,” fashioned into diamonds, exploded in fireworks, launched into space, or loaded into shotgun shells, rifle cartridges or bullets.

Four current options

In recent years, more people have sought newer ways, or resurrected older, simpler ways, to deal with human remains without using hazardous embalming fluids, steel coffins, concrete burial vaults or high-energy cremation. Here are some of the emerging options. Not all are available in all states.

Natural (green) burial

Shortly after death, your body is buried directly in ground with as little around it as possible — perhaps a biodegradable shroud or a casket made of cardboard, bamboo or light wood. Some 368 U.S. cemeteries allow green burial.

Emily Miller, founder of the Colorado Burial Preserve, says the natural process is the closest to the ancient practice of Jews and Christians. “This is ashes to ashes, and dust to dust,” she said.

The practice was popularized in the U.S in the 1990s by Billy and Kimberly Campbell of South Carolina. “The grave itself becomes a living thing; it becomes a composting unit,” Billy said. Today, the Green Burial Council advises people on their options.

Human composting as seen on a recent segment of CBS News

Human composting

Your remains spend 45 days in a steel vessel filled with water, mulch and microbes. Heat helps speed the natural decomposition process, which yields 45 lbs. of nutrient-rich soil and bones.

This method is currently legal in Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, California, New York and Nevada, with more states considering it. But like water cremation, below, is opposed by some religious groups that say it does not respect the body. The Catholic Church opposes turning human remains into “waste” products and opposes their use in gardens.

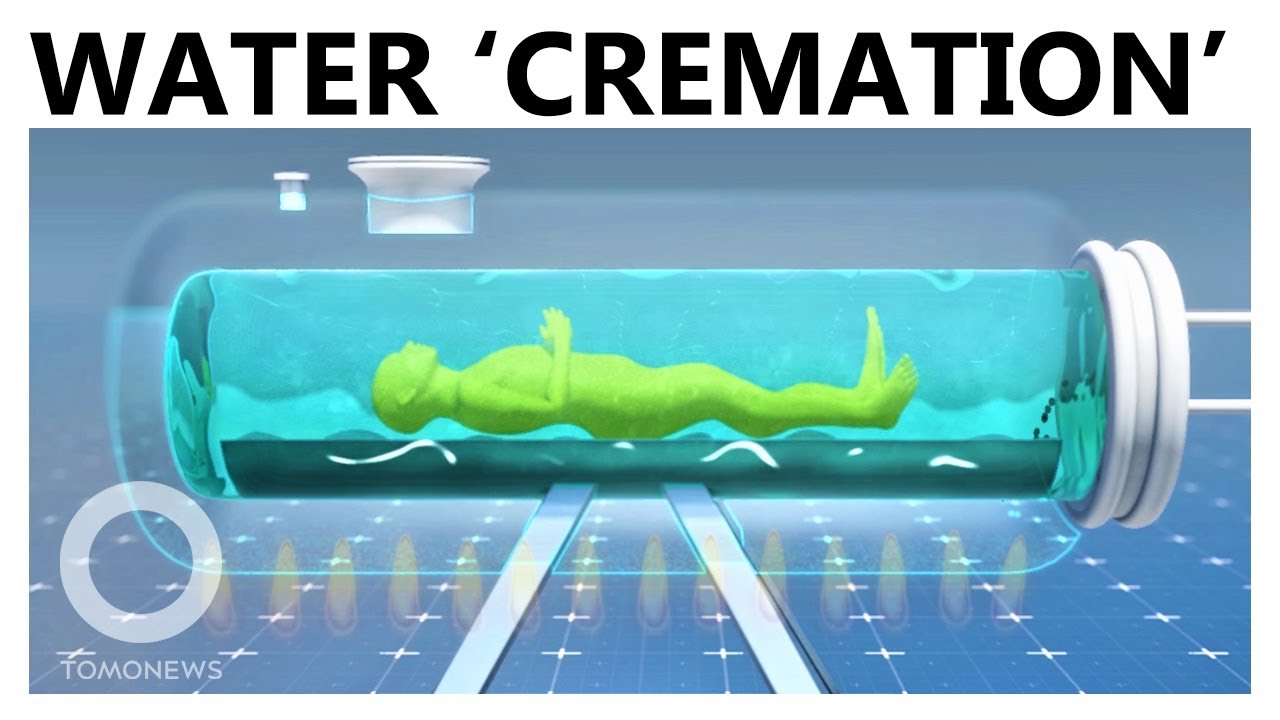

Water cremation (aquamation, Alkaline hydrolysis)

Your remains spend only four hours in a steel vessel filled with hot water and chemicals, yielding colored liquid and bones, which are ground up. Available since 2011, this process is now legal in 28 states. It was the choice of South Africa’s Bishop Desmond Tutu.

Donate your body to science

Every year, about 20,000 Americans donate their bodies for scientific use. As one person put it during a recent Sunday school class on last remains, “This body has served me pretty well so far in life. Once I’m dead, I would like it to serve someone else.”

She has registered with Science Care, a body donation program that offers no-cost cremation after your body provides organs to others who need them, or is used for study. Once she dies, Science Care takes care of everything at no cost: transportation, cremation, death certificate and permits and return of cremated remains.

Many medical schools hold memorial services for the people who donated their remains. “You’re able to think about the donor you’re working with,” a director at Point Loma Nazarene University told The New York Times.