Two giant questions leaped off the page as the interpreters of American religion began reading the latest data dump from Public Religion Research Institute July 8: How could this data about mainline Protestants be correct, and why is the data about the “nones” so different from what previously has been reported?

PRRI, which is the new kid on the block in terms of religion polling, has amassed a sterling reputation for releasing accessible data that interprets current trends, such as attitudes about the 2020 presidential election and attitudes about race. PRRI founder Robert P. Jones has drawn extensively on his firm’s research in his books, including his most recent acclaimed publication, White Too Long.

The other big names in religion polling are Gallup, Pew Research and Barna Research, with Gallup being the elder statesman of the group. But there also are two other sources of religion data that most laypeople are not aware of — sources that provide much of the raw data that scholars and statisticians crunch and interpret in hundreds of ways. These are the General Social Survey and the Cooperative Election Study.

One of the biggest stories of religion news in recent years has been the rapid growth of the “nones.”

Think of these last two sources as data wholesalers. They’re the equivalent of manufacturers who produce the products that end up on your grocery store shelves, although you as a consumer only interact with the grocery store and pay no attention to the wholesalers behind the curtain.

That’s the background to provide understanding of the latest polling from PRRI, which already has made headlines around the nation. Many of those headlines have focused on a reported increase in mainline Protestants or a reported decline in the percentage of Americans who identify as religious “nones.”

What’s happening with the ‘nones’?

PRRI’s cell phone and landline phone survey of 50,334 persons over the course of an entire year (2020) found that growth of the “nones” is slowing. “Nones” are those who when asked on other surveys what their religious affiliation is skip all the normal answers and instead chose “none of the above.”

One of the biggest stories of religion news in recent years has been the rapid growth of the “nones,” which is the subject of an entire book published earlier this year by Baptist pastor and social researcher Ryan Burge. The professor at Eastern Illinois University has become the nation’s foremost data cruncher on this group of Americans.

One of the biggest stories of religion news in recent years has been the rapid growth of the “nones,” which is the subject of an entire book published earlier this year by Baptist pastor and social researcher Ryan Burge. The professor at Eastern Illinois University has become the nation’s foremost data cruncher on this group of Americans.

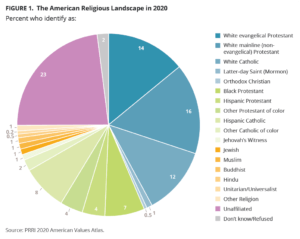

In his new book, Burge uses previously published data, including from the General Social Survey and Pew, to report that the “nones” currently comprise 34% of the U.S. population — up from just 5% of Americans in the 1970s and 22% in 2008. Thus, this has been dubbed “the fastest growing religious group in America.”

According to this perspective, atheists and agnostics each represent 6% of the population, while 21% of Americans identify as the more common type of “none” — people whose religion is “nothing in particular.”

The new PRRI data, however, calculates that religiously unaffiliated Americans comprise 23% of the population, including the “nothing in particular” (17%) and those who identify as atheist (3%) or agnostic (3%).

That’s an overall comparative 4-point drop in the fastest-growing religious group in America. And it counts atheists and agnostics at half the strength of other surveys.

PRRI’s answer is that the growth of the “nones” reached its peak in 2018 and now is settling back to slightly lower numbers.

PRRI’s answer is that the growth of the “nones” reached its peak in 2018 and now is settling back to slightly lower numbers. If true, that’s a spot of good news for the institutional church in America, which has been losing adherents by the thousands every year and fretting over how to reach the “nones.”

As the PRRI data have been public only a week, complete answers to questions about how one survey compares to another are not yet available. However, you can be sure this will be a topic of intense conversation and writing in the days to come.

One important note: PRRI points out that the increase in religious disaffiliation “has occurred across all age groups but has been most pronounced among young Americans.” And even though the likelihood of an 18- to 29-year-old being a “none” has dropped 2 points, the unaffiliated group still accounts for 36% of the young adult population — the largest percentage of any age group.

Decline of the mainline?

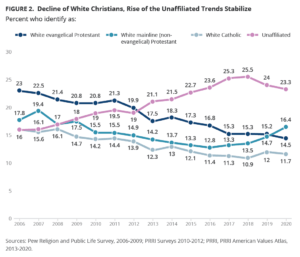

More vexing — and controversial — is PRRI’s report on mainline Protestants: “The slight increase in white Christians between 2018 and 2020 was driven primarily by an uptick in the proportion of white mainline (non-evangelical) Protestants and a stabilization in the proportion of white Catholics. Since 2007, white mainline (non-evangelical) Protestants have declined from 19% of the population to a low of 13% in 2016, but the last three years have seen small but steady increases, up to 16% in 2020.”

Thus the headlines in major daily newspapers declaring a miraculous reversal of fortunes for mainline Protestants.

Thus the headlines in major daily newspapers declaring a miraculous reversal of fortunes for mainline Protestants.

Ryan Burge, the professor who studies the “nones,” weighed in on this one. His message: Wait a minute; don’t get too excited about this. His reason for caution: Internal data from all the mainline denominations continues to show precipitous declines in membership and participation.

Sidenote here: Perhaps you’re wondering who is a “mainline” Protestant. That’s a good question with a complicated answer.

Historically, the mainline has included the so-called “Seven Sisters,” which are the United Methodist Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Presbyterian Church (USA), the Episcopal Church in America, American Baptist Churches USA, the United Church of Christ, and the Disciples of Christ. Plus a few other smaller groups. Depending on who’s counting.

A notable distinction for Baptists is that American Baptist churches are counted among the mainline but Southern Baptist churches and most Black Baptist churches are not. Southern Baptists typically get counted among evangelical churches. Newer Baptist groups such as the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship seemingly fall between the cracks of statistical categories.

Burge explains that most religion researchers think of three kinds of Protestants (and by the way, there’s a whole separate conversation to be had about whether Baptists are technically Protestants anyway). Those categories are evangelical, mainline and historically Black Protestants.

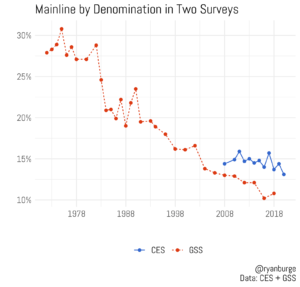

The wholesale data that researchers like Burge have used to chart a continued downward path for the mainline shows its share of the American market to be about 12%, down from 30% as recently as the 1970s. And the combined data reported by those denominations also parallels the same dramatic declines.

“The United Methodists lost 2.25 million members over 10 years, a 15% decline. The ELCA dropped 750,000, a decline of 22%. The PCUSA is down 40% between 2009 and 2020, and the Disciples of Christ are also down 40%. In fact, there’s only one tradition — the American Baptists, where membership is only down single digits over the last decade,” Burge said.

“The United Methodists lost 2.25 million members over 10 years, a 15% decline. The ELCA dropped 750,000, a decline of 22%. The PCUSA is down 40% between 2009 and 2020, and the Disciples of Christ are also down 40%. In fact, there’s only one tradition — the American Baptists, where membership is only down single digits over the last decade,” Burge said.

“This analysis alone indicates that there are six million fewer members of these seven traditions than just a decade ago. It’s hard to conceive of a situation where these denominations are losing hundreds of thousands of members each year, yet the overall mainline tradition is growing in size.”

How, then, to account for the new PRRI data that shows a “small but steady increase” in the mainline?

The answer most likely is found in how the survey questions are asked, Burge said. Other surveys, including the General Social Survey and the Cooperative Election Study, use a series of “branching” questions in their polls that take respondents down a path of answering “are you this or that?” and then “are you this or that?”

PRRI uses a different, and also valid, approach. “The first question is about broad religious tradition,” Burge explained. “This includes response options like: Protestant, Catholic, Mormon or atheist. Then, respondents are asked if they identify as ‘evangelical or born-again’ or not. If they say that they are Protestants and self-identify as evangelical, then they are evangelicals. But, if they say they are Protestant but don’t identify as evangelical, then they are mainline. Using this approach compared to the denominational strategy can lead to slightly different estimates.”

However you slice the data, though, “there is one clear and unmistakable conclusion,” Burge said: “The largest traditions in the mainline are losing members at an incredibly rapid rate.”

Coming tomorrow: The new PRRI data digs down to a county-by-county level to offer some of the most localized insight on religion politics available anywhere.