Dietrich Bonhoeffer railed against cheap grace that’s given “without asking questions or fixing limits.”

Kaya Oakes targets “quick forgiveness,” a form of spiritual abuse practiced by powerful, charismatic and sexually predatory Christian leaders who pressure victims to quickly forgive, forget, bless their offenders’ speedy return to the ministry spotlight, and save the institution — be it a church or religious nonprofit.

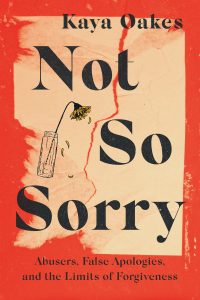

“When a person’s body or spirit or mind is violated and the violator asks to be forgiven, the wronged person must make a decision: Do I do this, or not?” Oakes writes in one of the many probing ideas that fill her thought-provoking sixth book, Not So Sorry: Abusers, False Apologies, and the Limits of Forgiveness.

Kaya Oakes

Oakes is a poet, journalist and writing instructor who left and later returned to the Catholic Church. She is a victim of sexual abuse (although not by Catholic clergy). She rails against the notion that those wronged must forgive every wrongdoer of everything and comforts those whose experiences with quick forgiveness reveal the offender’s power, not his (it’s usually a he) repentance.

“Jesus asked us to forgive those who know not what they do. But what do we do about the people who knew exactly what they were doing?” writes Oakes, who makes a solid case for not forgiving those who either don’t seek forgiveness or seek it in all the wrong ways.

“Some things are unforgivable,” she writes. “Sometimes it’s simply OK to say, ‘I can’t forgive this person, or this institution, or this historical wrong. I can’t even promise that I’ll get there eventually.”

Oakes explores biblical passages, challenging commonplace theological notions, such as the idea that Christians will lose their salvation if they don’t forgive those who’ve abused them.

She also takes readers on a guided tour of church history, showing how understandings of forgiveness have evolved since the time of Jesus, whose Jewish upbringing taught that forgiving is just one part of a larger process of atonement and reconciliation.

Martin Luther’s emphasis on salvation by grace alone announced the “Protestant emphasis on forgiveness without the mediation of clergy,” which yields believers who “see forgiveness as a more individualistic process than the idea in the Hebrew Bible that it is meant to bring a person back into community.”

Many Americans practice a secularized form of forgiveness that “can lead to an erasure of history for the sake of the person or the country that feels a need to move on,” but this approach “can lead to persistent and pervasive forms of abuse,” she says.

American evangelicals took Luther’s individualized forgiveness and ran with it, and in many churches, “there is little or no accountability for pastors beyond their congregations.”

Oakes’ parade of offenders offering nonapology apologies is ecumenical, including:

Oakes’ parade of offenders offering nonapology apologies is ecumenical, including:

- Catholic Cardinal Theodore McCarrick abused seminarians for decades, insisted on his innocence, and said, “I am sorry for the pain the person who brought these charges has gone through.”

- Mennonite theologian John Yoder abused at least 100 women over decades but could only say he “was sorry that (victims) had misunderstood his intentions.”

- Evangelical Mark Driscoll practiced emotional abuse at Mars Hill Church in Seattle, claimed he had changed, then practiced emotional abuse again at Trinity Church in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The antidote to quick forgiveness is a return to the Jewish traditions Jesus knew best, which taught that forgiveness “is not the first step … of atonement and repentance It is the final step,” she advises.

Instead of rushing the forgiveness process, offenders first must take concrete steps, including publicly naming and owning the harm they have caused, showing what they’re doing to change their behavior, accepting the consequences of their actions and offering some form of restitution.

For some, forgiving everyone everything can be freeing. But for others who have endured the one-two punch of abuse and pressure to issue quick forgiveness, Oakes shows it’s OK not to forgive unrepentant monsters, and this can be freeing, too.

Related articles:

Archbishop of Canterbury sets an example of accountability | Analysis by Christa Brown

‘What can we forgive?’: An interview with Matthew Ichihashi Potts on Forgiveness | Analysis by Greg Garrett