It seems no matter what table a Christian chooses to sit at these days, powerful men are determining who gets a seat, when they can talk and what stories they’re allowed to tell.

This marginalization of voices on the underside of sacralized machismo is evident in three stories from this past week.

These controversies involve Elizabeth Elliot, Beth Allison Barr, Kristin Du Mez and Karen Swallow Prior. And they all relate to the reach of patriarchy’s table and how we should respond — what we should say and shouldn’t say.

Let’s start with the late Elisabeth Elliot. She first came to public attention after her first husband, Jim, was murdered by Amazonian warriors from the Waodani tribe of Ecuador in 1956. He and his fellow missionaries had attempted to share the story of Jesus with the tribe.

Elisabeth Elliot spent two years as a missionary to the tribe that killed her husband. After returning to the United States, she spent five decades publishing 48 books, speaking internationally and hosting a daily radio show, which made her the icon of purity culture and the queen of complementarianism in conservative evangelicalism.

Elliot’s evolution

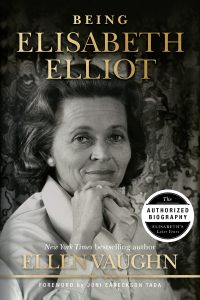

The uproar this past week began with an essay by Liz Charlotte Grant that focused on the trajectory of Elliot’s life as revealed in two biographies published in 2023 — Lucy R.S. Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life and Ellen Vaughn’s Being Elisabeth Elliot.

Despite where she ended up, Elliot began her career speaking her own mind. She taught both men and women and criticized Christian publishing for “making stories ‘neat and tidy.’” Grant observed, “This Elliot courted the ideas of feminism and gained a reputation as being argumentative and opinionated.”

Despite where she ended up, Elliot began her career speaking her own mind. She taught both men and women and criticized Christian publishing for “making stories ‘neat and tidy.’” Grant observed, “This Elliot courted the ideas of feminism and gained a reputation as being argumentative and opinionated.”

Elliot married three times in her life, with each marriage seeming to become increasingly more dysfunctional over time. Her first marriage to Jim served as the inspiration for her writing. Her second husband, Presbyterian seminary professor Addison Leitch, was described as traditional and institutionalist. He once wrote, “The conversation around women’s liberation is ‘stupid.’” During their marriage, Elliot became more institutional herself and began teaching women to have “unconditional obedience” to their husbands.

Her third marriage is the focus of the current controversy. According to Grant, Elliot’s husband Lars Green “decided when she drank a cup of tea, took a bath, and when she slept. He frequently checked her car’s odometer, double-checking that she hadn’t made any unplanned stops. He controlled the house thermostat. He listened in on her phone conversations and had the final say on whether she visited her friends, often declining invitations for her at the last minute.”

He also kept her away from her children and grandchildren. And he forced her to maintain a rigid speaking schedule, which culminated in her sitting on stage and smiling during her battle with Alzheimer’s while recordings of her teaching played.

Silencing the ‘slander’

Much of the debate among complementarians started when Aimee Byrd quoted Grant on X, saying: “White American evangelicalism needed a symbol, a meek female voice seated at the patriarch’s table — and Elliot complied.”

“What vile slander. You will receive your reward,” wrote one person self-identifying as “Homemaking Theogal.”

“What an utterly stupid take!” added Josh Buice, pastor of Pray’s Mill Baptist Church and founder of G3 Ministries.

“It’s amazing how quickly the cancer of feminism grows in apostates.”

“It’s amazing how quickly the cancer of feminism grows in apostates,” posted another.

Then Owen Strachan, former president of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, chimed in: “It’s unseemly to target a dead woman’s marriage. … This is a hit-piece.”

Strachan doubled down, claiming: “The targeting of Elisabeth Elliot and Lars Gren’s marriage (which may well have had real problems) accomplishes a vile effect: It makes it harder for complementarian couples to be honest about the imperfection of their marriage, as we all need to be.”

Then he added: “Attacks on complementarians who face real marital challenges (as every couple on planet earth does) poisons the well. It stigmatizes those who need help. It shames the struggling. Hear me clear as a bell: there’s nothing of Christ, and gospel mercy and grace, in such attacks.”

A gospel of self-sacrifice and submission up the hierarchy

Complementarians like Strachan want to silence narratives about abuse because they interpret marriage as a picture of Christ and the church, but with a hierarchy running from God the Father down through Jesus and on down to husbands who rule over women and children. Those who are on the underside of each dynamic must submit in self-sacrifice to the person above them. To them, these power dynamics are good news.

New Testament scholar Laura Robinson explains: “Elisabeth Elliot’s written work is, on the whole, geared towards the theme of self-sacrifice — that giving things up, humbling yourself, following God, and rejecting personal desires or feelings is the way of the Cross. … This message of self-sacrifice up to and including self-martyrdom is a message that Christian people have returned to again and again through history.”

The dual framing of headship and submission requires women to submit themselves to men, while men exercise headship and authority over women.

So while themes of self-sacrifice are to some degree inseparable from the Christian story, they can be given what Christian ethicist Kate Ott calls “a gendered twist” that harms women.

In other words, we cannot simply celebrate terms like “the gospel” or “the story of Jesus” without reflecting on how our framing of the story might reinforce abusive power dynamics over the oppressed.

Thus, to Robinson, the theme of losing one’s life, “must have some kind of limit.”

A ‘woefully flat’ history?

The second controversy this week came from Messiah University history professor John Fea. Writing for The Atlantic, Fea shared the story of his abusive agnostic father who became a Christian, followed the teaching of James Dobson and became a kinder, gentler man.

Beth Allison Barr

Despite Fea’s earlier support of Kristin Du Mez’s Jesus and John Wayne and Beth Allison Barr’s The Making of Biblical Womanhood, Fea singled out the two historians and accused them of telling a story of American evangelicalism that is “woefully flat” and that doesn’t take into consideration “millions of other men and women who learned from Dobson how to love their families as Jesus loves his church.”

Barr responded on Threads: “Let me just be transparent. I’m pretty angry about what John Fea wrote about me and Kristin in the Atlantic.”

She later added: “I grew up Baptist. I learned who God is from my Baptist Sunday school teachers. I met Jesus at a Baptist camp. I fell in love with a Baptist pastor and our Baptist pastor officiated our wedding. Yet, during all of it, Baptists were turning a blind eye to sexual predators even as harmful theologies such as the subjugation of women and purity culture were flourishing. Calling out evil doesn’t erase good. Calling out evil is the only way to get rid of evil before it overwhelms the good.”

Telling all the stories

Despite the fact Fea thinks the coverage of evangelical patriarchy is too negative, Du Mez responded by pointing out how the reality in Christian publishing is quite the contrary.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

“In crafting the argument that coverage of evangelicalism is ‘too negative’ and that ‘the whole story’ isn’t being told, Fea neglects to mention the scores of books evangelicals write about themselves for themselves,” Du Mez explained. “Don’t be fooled. These books outsell all the ‘negative’ takes by an order of magnitude. Tune into Christian radio, and you’ll hear nothing but glowing reports of evangelicals ‘doing the Lord’s work,’ wherever they go.”

Du Mez argued: “Jesus and John Wayne and The Making of Biblical Womanhood became bestsellers not because a secular public couldn’t get enough of ‘evangelicals behaving badly.’ They became bestsellers because evangelical readers themselves found them and said, ‘This is true.’ After decades of being fed only one narrative — all of the positive stories and celebrations of how they, more than anyone else, were ‘doing the Lord’s work’ — tens of thousands of evangelical readers found in our books accounts that resonated with their own experiences.”

It’s true that patriarchy is bigger than Christian patriarchy. So there are stories of men like Fea’s father who became kinder, gentler patriarchs when they became Christians. But that doesn’t mean patriarchy in society or in Christianity needs to go unchallenged. It simply means all the stories need to be told in perspective.

You don’t have to be this way

The third controversy came through an open letter written by Karen Swallow Prior to the Southern Baptist Convention.

Pointing out how the SBC was formed “by slaveholders for the purpose of defending the institution of slavery,” Prior charged Southern Baptists that they “don’t have to be this way” and reminded them of their claim to believe in “good news for the whole world.”

Karen Swallow Prior

“Last time I checked, the whole world includes everybody,” she reflected. “And everybody includes those inside the church who have been abused.”

But rather than the SBC listening to the stories of harm they’ve caused, Prior noted how they “listen instead to the whispers of abusers” and “young, fresh flatterers whom you groom into your own image and likeness, thereby ensuring that nothing ever really changes.”

Responding to Prior, Founders Ministry president Tom Ascol posted, “Dear KSP, You don’t have to be this way. For the sake of truth, The Church.”

Obscuring the truth that could heal

In each of these three controversies, men are telling the oppressed they’re talking too much. So it should be no surprise when we hear story after story of abuse happening at their tables.

“Men are telling the oppressed they’re talking too much.”

In Grant’s piece about Elliot, she asks, “What do evangelical institutions today gain by obscuring the truth about Elliot’s third marriage? What makes them so hesitant to admit the failures of their leaders when doing so might offer healing to their victims?”

In the controversy between Fea, Du Mez and Barr, Fea reacted against two books he deemed to be telling stories about Christian patriarchy that were too negative.

In Prior’s piece, she pointed out how conservative patriarchs refuse to listen to the stories of people they’ve oppressed too. “You invite people to the table only for the sake of their different faces, not to listen to their voices,” she argues. “If you listened, you’d have to hear stories, experiences and perspectives that don’t reinforce your preferred narrative.”

Invited to the tables

Perhaps the solution to each of these controversies is for Christians to come out from patriarchy’s table Grant mentioned and accept an invitation to the table of listening Prior mentioned.

In the early church, the Communion table was more than merely a sacrament celebrated once a month by Christians. Instead, the table invited everyone regardless of their status in first century Greco-Roman empire hierarchies to face one another side by side in mutual belonging, interdependency and union.

“Before the Communion table ever existed, Jesus himself sat at tables with those the hierarchy considered to be ‘sinners.’”

In the circle of sharing meals, men and women, adults and children, free and slave, Jew and Gentile, all shared their stories. And since their stories throughout the week were experienced from drastically different perspectives of the empire’s hierarchy, they had to face experiences and perspectives that didn’t reinforce their preferred narratives.

Of course, in today’s Christianity, even the concept of the table itself is a controversy. Who is welcome at the table? Is it exclusive to Christians? What constitutes a Christian? Even those claiming to be Christians referenced in this piece have a variety of perspectives to these questions. And if, as some have suggested, even the likes of Aimee Byrd are apostates, then God knows I wouldn’t have a seat at that table given my theology.

But rather than arguing over who belongs at the Communion table, it doesn’t matter because before the Communion table ever existed, Jesus himself sat at tables with those the hierarchy considered to be “sinners.”

So whether you choose to sit at the table with Christians or at Jesus’ table with sinners, either way you end up in the same place — eating, drinking and conversing with other oppressed people who are different from you, and hearing everyone’s story regardless of how the powerful men at the top harm or exclude them.

As Du Mez said: “One person’s story shouldn’t cancel another’s. Some stories have been kept hidden for a very long time, by design. … Let’s grapple with how all of these stories exist within the movement side-by-side, within communities and within churches, and sometimes within families. And let’s do so with integrity.”

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.