After consolidating his power over the Bob Jones University board of trustees last week, Chairman John Lewis won his face-off against university president Steve Pettit.

Pettit, who has served as president of the ultra-conservative school since 2014, had given the board an ultimatum before last week’s meeting: “I cannot continue to work in a relationship with Dr. John Lewis as chairman of the board. … You will have to make a choice between two possible outcomes.”

Lewis proceeded to remove two board members supportive of Pettit, bring in five new prospective trustees presumably sharing his views and concentrate trustee power in a six-person Executive Committee he directs.

Pettit resigned.

“This is about one of the school’s founding namesakes collaborating with a powerful trustee chairman to turn back the clock.”

What’s going on here is more than meets the eye to an outside observer. This is about one of the school’s founding namesakes collaborating with a powerful trustee chairman to turn back the clock.

Back to the future

In his ultimatum letter to the board, Pettit said trustee Executive Committee meetings “have been moved to Bob Jones III’s residence,” implicating the grandson of the university’s founder in Lewis’ plot. Pettit also claimed Lewis kept meetings secret from the university’s corporate counsel, refused to release meeting minutes in a timely way to other trustees, stored “sensitive board documentation … outside the university’s secured network on a new computer purchased at the chairman’s instruction,” and altered the board’s portal “to prevent or hinder trustees from printing documents.”

Bob Jones III

Pettit also claimed Lewis requires all requests for information about the board to run through him exclusively and that Lewis hired a new lawyer to advise certain members of the board without the other members knowing.

With these tactics, Lewis and Bob Jones III together set the table to recover from what Jones refers to as “some embarrassing, antithetical things, historically uncharacteristic things.” According to Jones, they had “to stop the hemorrhage.”

What hemorrhage? The appearance of wokeness.

Among recent events Lewis and Jones and their allies believe have damaged the university’s fundamentalist credentials:

- A male fashion student wearing a wrap coat some board members thought made Jesus look like a gay man.

- Former Clemson quarterback Trevor Lawrence being invited to speak at a fundraiser despite the existence of a photo of his fiancé wearing a bikini on Instagram.

- Female student athletes wearing shorts too far above their knees during competition.

- BJU’s recent performance of the Disney musical Beauty and the Beast.

Meanwhile, the obsession with controlling and covering women’s bodies has led to a Title IX investigation, one of the trustees apparently is being investigated for making a public comment about whether female students’ clothing and female student athletes’ uniforms accentuate their “boobs and butts,” and a trustee is alleged to have taken photographs of female students without their consent.

“Why do Lewis and Jones feel the need to control people like this? And what do they think gives them the right to do so?”

Why do Lewis and Jones feel the need to control people like this? And what do they think gives them the right to do so?

While many may be familiar with Jones, given the decades he and his family spent in the public eye, far fewer understand anything about Lewis, who is the former pastor of Faith Baptist Church in Davison, Mich.

I’m a Bob Jones University graduate, and I didn’t know who Lewis is. So I listened to 10 of his sermons, which are laced with personal history and interpretation. When you learn his background and listen to his preaching, his obsession with power over others makes sense.

His mother’s favorite word

One of the most common stories Lewis tells in his sermons is how his relationship with his mother growing up affected his outlook on authority and rules today.

After Lewis’ parents split up when he was 12 years old, he and his mother moved into a government housing project in North Carolina, he said. “All the boys it seemed were either going to jail or going in the military.

“And my mother’s favorite word to me was, ‘No.’ Almost anything that I would ask, it seems that she would say no. I’m a little bit older now and I understand why she said no. But I used to tell my mother, ‘I can hardly wait until I get old enough to leave home. I’m tired of people telling me what to do.’”

Three days after turning 17, Lewis decided to break from the family rules and join the military.

“I was in for a rude awakening,” he explained. “I thought my mother knew how to use that word ‘no.’ But I found out the United States Air Force knew how to use it. And then it seemed that anything that I wanted to do was wrong. It seemed that all you ever heard was that you were a numskull or something. You just had somebody breathing down your throat all the time telling you no. You can’t do this or you’ve got to do this. I thought I was leaving authority. I thought I was leaving somebody that was always telling me what to do.”

In one sermon, he recalls his drill instructor being a “great big gorilla of a guy” who had been court-martialed for hitting another soldier and breaking his ribs.

One morning, after Lewis failed to make his bed well enough, the drill instructor stood nose to nose with Lewis yelling at and humiliating him. Then the instructor punched Lewis in the stomach.

“He taught me in three minutes that day what my mother couldn’t teach me in 17 years.”

Lewis tells this as a positive story: “He taught me in three minutes that day what my mother couldn’t teach me in 17 years.”

He served in the Air Force from 1963 to 1967 and fought in Vietnam.

From the top of the business world to the top of the church

After serving in the military, Lewis moved to Guam and went into upper management at what he says was the largest financial enterprise in the country.

While there, Lewis became a Christian. And six weeks later, he felt called to preach.

John Lewis

“God called me to preach six weeks after I got saved. I had a high school GED, no college. But I knew God called me to preach,” he recalls. So Lewis pursued an education at Free Will Baptist College in Nashville, Tenn.

During his second time working for the financial company in Guam, Lewis was attending Harvest Baptist Church. When the pastor at Harvest left, the church asked Lewis to become their new pastor. Lewis says he was so successful in the financial world that the owner of the company tried to keep him on the payroll. But Lewis made a clean break for the opportunity at Harvest.

During 19 years as pastor at Harvest Baptist Church, the ministry “grew from under 30 adults to over 400, established a Christian school, a three-year Bible institute and an FM radio station.”

Bullying a woman while Bob Jones III snickers

Lewis and Bob Jones III first met at the 1980 Congress of Fundamentalism in Manilla, Philippines, and, according to Jones, became like brothers.

Two years into Lewis’ ministry at Harvest, he invited Jones to speak for a week of revival meetings. On the final night of the meetings, Lewis asked the congregation if anyone wanted to share a testimony. When a woman on the front row raised her hand, Lewis said he ignored her. Claiming the woman was getting frantic, Lewis decided to let her share.

“Ma’am, if an angel came and sat down on your bed and talked to you last night, it was because you ate too much of the wrong thing before you went to sleep. Sit down!”

When she shared a testimony about an angel sitting on her bed, Lewis responded in front of the church, “Ma’am, if an angel came and sat down on your bed and talked to you last night, it was because you ate too much of the wrong thing before you went to sleep. Sit down!”

Lewis added, “When I turned around when it was over, Dr. Bob was still snickering in the back.”

Joking about women is a common theme in Lewis’ sermons. During chapel and Bible Conference sermons at BJU, Lewis jokes about a woman “going nuts” during a sermon by Bob Wood, about women jumping up on the chairs over a rat, about a woman divorcing her husband for not talking to her only to reveal it was because she wouldn’t stop talking, and about somebody marrying a cross-eyed woman. In every case, the audience roars in laughter.

The ‘Bob Jones of the North’

Lewis’ friendship with Jones led to an invitation to join BJU’s Cooperating Board in 1991. He later joined the trustee board in 1997 and its Executive Committee in 1998.

During that same year, Lewis accepted an invitation to leave Guam and become pastor of Faith Baptist Church in Davison, Mich., where he remained until 2014.

In interviews with Baptist News Global, sources close to Faith said Lewis’ time in the military appeared to have a huge influence on the way he led the ministry, including coming up frequently in sermons and in the operation of the church. Military themes also were prevalent in men’s conferences and in worship songs about being soldiers for God.

Lewis’ experience in the financial world gave him the ability to dig Faith out of a difficult financial situation and create financial transparency.

Likely due to the time he spent in the racially diverse Guam, he reportedly stayed away from the controversies around race that Jones — like his family before him — entered into throughout the years.

While BJU refused to allow interracial dating until 2000, Lewis’ local school reportedly didn’t share the same ban. Of course, being an overwhelmingly white high school steeped in purity culture that highly discouraged dating altogether meant the topic didn’t come up as much.

But despite some such differences, other churches and schools in the Davison area called Faith “the Bob Jones of the North.”

Like Jones in the South, Lewis controlled every area of the church and school, including the areas he had no experience in. Like BJU, Faith students were forbidden from listening to any form of contemporary rock music, including contemporary Christian music. Dancing was off limits. Movies or television shows were limited mostly to G-rated programs. And dress codes were strictly enforced.

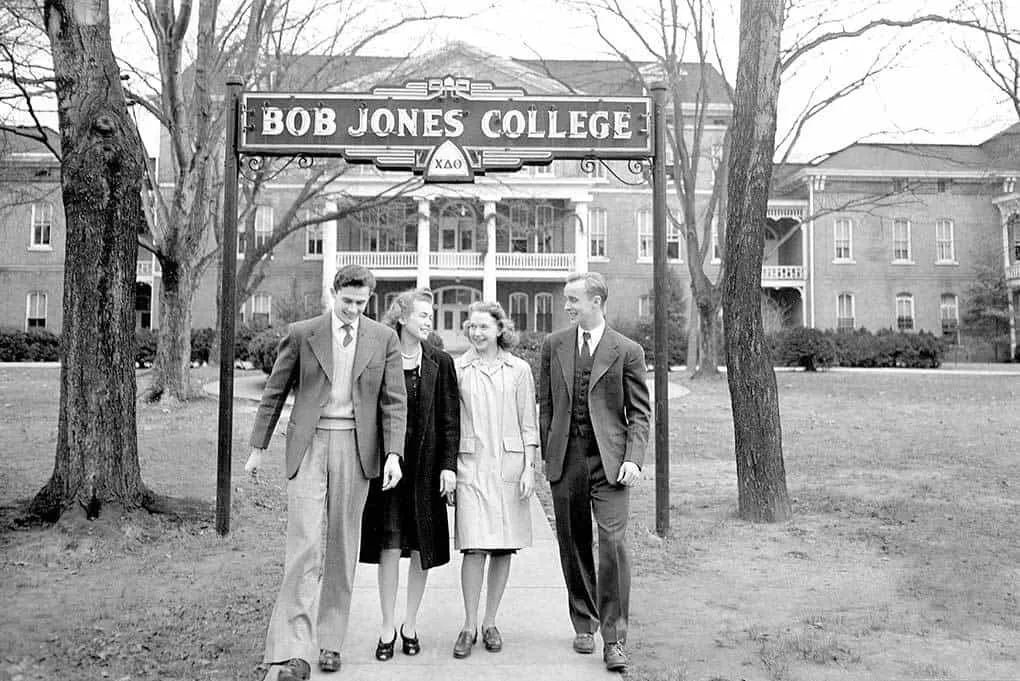

Undated publicity photo from what was then Bob Jones College.

Jones came to speak at the church multiple times each year and spoke often at the school’s commencement ceremonies.

Lewis retired from Faith in 2014 and is no longer a part of the leadership there. Two years later, he was elected chairman of the board for BJU.

That was two years after Pettit became the first president in the school’s history not to be part of the founder’s family and carry the name Jones.

Deserving hell and refusing to gripe

One of the ways Bob Jones III left his fingerprint on Lewis’ Michigan school was through a fear of hell. Both BJU and Faith chapel services regularly included a schtick from Jones where the speaker says, “The most sobering reality in the world today is that,” and then the congregation responds with, “People are dying and going to hell today.”

“When we come to grips with the fact that what we deserve is hell, then anything else is a bonus.”

In a sermon at BJU, Lewis said: “When we come to grips with the fact that what we deserve is hell, then anything else is a bonus, we will have made some progress in our life.”

To Lewis, once eternal conscious torment is the baseline for what humans deserve, even the most violent and oppressive situations should be considered a bonus. Accepting such violence against the self is where he thinks progress happens because it lowers the identity of the listener to someone deserving of violence and frames the actions of those in power over them as a bonus.

Thus, Lewis says true Christian students will accept the myriad of rules from the school without speaking up for themselves.

“When you find somebody that’s griping and moaning and unhappy with the rules and always chafing under authority, you don’t need them,” he said at a BJU chapel service. “The founder of this institution, Dr. Bob Jones Sr., realized at the very beginning the corrupting influence of gripers. You’ve read, you’ve heard, if you stay here you’ll hear it again, ‘No griping tolerated.’ Why? Because he’s a wise man. He knew the corrupting influence of griping.”

Seeing reality through the lens of masters and slaves

Reality, according to Lewis, is a hierarchy of ruling and dominating. Prior to becoming an evangelical, the “old nature likes to rule and dominate,” he says.

For evangelicals, however, there is an alternative hierarchy, Lewis says. “We’re under grace. Being under grace, saved by grace, we’re free from guilt and the power of sin. We’ve got an alternative now. It doesn’t have to control our lives. We’re free from the corruption of sin and the penalty. And we’ve received the blessing of God’s grace. And it ought to produce in us a loving obedience.”

“Lewis wields grace as a way of telling students to submit to him and to love it.”

With that turn of phrase toward “loving obedience,” Lewis wields grace as a way of telling students to submit to him and to love it.

“There may be some sitting here tonight that because of rules here at the school or rules at home, it’s produced rebellion in you. You’ve just had it up to your eyeballs with somebody telling you what you can do and what you can’t do,” he said. “You’re going to serve somebody. There’s no such thing as absolute freedom where you can just go through life. You’re going to serve somebody. You’re going to have a master. You’re going to be somebody’s slave.”

The point appears to be this: Lewis and BJU are the masters, and students and employees are the slaves.

Controlling employees and students as slaves

In a sermon titled “The Freedom Found in Serving a New Master,” Lewis talks about people who use “soul liberty” as a way of claiming that “we have no right as a ministry to set guidelines for them.”

He tells the story of a staff member at another church who said they couldn’t sign the rulebook. So the pastor asked Lewis how he would handle it.

“If it was a young staff member, somebody that’s maybe just out of college, I would make sure they understood why we had the rules,” Lewis responded. “Then if they refused to sign it, I said I would fire them.” He added, “If it was an old timer, if it was somebody in leadership, and they took this attitude, I said I would fire them immediately.”

Then Lewis concludes: “You’re going to serve somebody. This man wanted to serve self, didn’t want any authority over him.”

When I was a student at BJU from 2000 to 2004, I often felt the administration treated us as children. After all, they used the phrase “en loco parentis” to give themselves the power of parents over the students. But given how Lewis uses the language in the Bible about being a slave to God as an example of students submitting to and serving those in authority over them, it’s clear he sees students as lower than children. He sees them as his slaves.

Seeing students as slaves also explains why a board member would think they have the right to take photos of female students’ bodies without their consent.

An obsession with sex and a fear of women

One of the most effective ways Lewis and Bob Jones University have wielded power over students is by disembodying them through shame about their sexuality.

Lewis says, “If you’re doing things that you shouldn’t be doing in your dorm room, if you’re living like the devil — let’s just cut it down to simple truth — if you’re living like the devil when you have the privacy of your room where nobody can see what you’re doing when you’re living like the devil, you’re serving the wrong master. … I would venture to say that with a crowd this size that there are folks here today that tonight you want to serve the Lord. Tomorrow, when you have a private time, you serve another master.”

In another sermon, he tells students coming home from Christmas break that if they did something under the cover of darkness over Christmas break, then God won’t be able to bless BJU until the student confesses it. “Every day that you have a sin in your heart is a day that’s marred,” he says.

He shares another story of a time when the back door of his church opened and a “strikingly beautiful” woman walked in who was “dressed very appropriately, a godly looking young lady.” But then she didn’t return for another year. Then one Sunday, she came back. But Lewis said: “Gone was the beauty. Gone was that innocent look of this girl. Instead of being the 23 to 25 years old that she was, she looked 40 years old.”

As the woman walked to the front, Lewis described, “Her marred face became a reality. Because of a sexually transmitted disease, she had sores on her face. And she looked horrible. She absolutely looked horrible.”

Lewis claimed the woman said she was homeless, was living in the back room of a bar as a prostitute, and that he never saw her again.

But in reality, college students are going to become sexually aroused on a regular basis. It’s a biological desire that will be present daily for most of them. So whatever narrative a preacher attaches to that desire will be a narrative often on their minds, especially when the preacher trains them to see sex everywhere.

By fantasizing about a woman’s striking beauty, calling her a girl, scaring people about STDs, and talking in vague terms about masturbation with threats of wasting your life and the potential of the entire school simply because you masturbated one morning, he is creating a mental link from sexual arousal to a wasted life and creating fear of women’s bodies.

And what we fear, we control.

Being healed from our wounds of control

Bob Jones Sr.

In an email to students announcing his resignation, Pettit said, “God is in control.” In an address to students the next day, he said: “God is on his throne. He hasn’t moved at all.” Many graduates who support Pettit have echoed these words on social media.

It makes sense within the evangelical paradigm to focus on God’s control given how Lewis and Jones have exerted their control over the school.

But the control Lewis and Jones wield goes far beyond simply BJU itself. It also extends to churches that have had to enforce many BJU rules in their own congregations out of fear of becoming “blacklisted” if they offend or cross the university.

“Every church in Greenville has wounds from BJU. And every former student has worse wounds.”

Camille Lewis, who was a professor at BJU for 17 years and is unrelated to John Lewis, explains in an online post: “Every church in Greenville has wounds from BJU. And every former student has worse wounds.”

John Lewis also has wounds. They go back to the stories he tells of constantly being told no as a child after his father left, of having somebody breathing down his throat all the time, of being made to feel like a numskull, and of being physically beaten.

Given his unhealed wounds, it adds up why he would use the physical violence of hell to justify shaping the identity of students by creating an educational environment of breathing down their throats and constantly telling them what to do. Anyone who has attended BJU will recognize similarities of how they were treated at BJU when reading the way Lewis was treated growing up.

But given how the metaphor of slavery has been abused by men who sacralize their power over others, maybe the lens of who is in control is not the lens we need to be looking through right now. What if we could be healed from our entire paradigm of control over others altogether?

Let’s be done with the slave metaphors

The barrier to healing lies with how we read the Bible and define the gospel. As Lewis shows in his preaching, the Bible utilizes first century slave language to talk about our relationship with God. Paul refers to himself as a slave. How could inerrantists do anything other than define their relationships in the same way? After all, it’s biblical.

No matter what one believes about inerrancy, using the Bible’s slave language to shape 21st century human relationships causes undeniable harm.

The trajectory of Scripture works to free us from relationships of slavery. Shouldn’t we then be freed from relating to God and one another in slavery metaphor language? Rather than getting caught up in debates about the differences between first century slavery and modern slavery, what if we moved on from the metaphor altogether? There is no reason for us to model our modern relationships on ancient slavery social structures that even conservatives would agree the gospel eradicates.

Of course, that depends on how we define the gospel. For Lewis, the “good news” of grace is a way of describing reality as a dominion hierarchy to demand loving obedience from slaves to masters.

But we ought to be reminded during this Passion Week that Jesus subverted all the first century Roman empirical power hierarchies by being lifted up on a throne that was a Cross.

Perhaps this week — in addition to considering some therapy — healing could come through the preaching of the Cross with an atonement theory of presence and love that the perishing Bob Jones University, obsessed with authority and power hierarchies, would have traditionally considered to be foolishness.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related article:

Bob Jones University president resigns in battle with board chairman