One of the most notable differences since leaving conservative evangelicalism has been my body’s reaction to justice-themed events on the calendar.

If the day or month had something to do with LGBTQ people, my immediate reaction would be one of defiance. These events were celebrating sin, I reasoned. And thus, our posture toward them had to be absolute rejection.

If the day or month had to do with bringing attention to abuse, my immediate reaction would be one of deflection. Sure, I would admit abuse is bad. But I figured people who focus on abuse tend to have victim mentalities rather than forgiveness toward those who hurt them. In other words, I would deflect the blame for the current relational strife on the victim rather than on the abuser.

Black History Month was a bit more complicated. With a passing nod to vague sins of the past committed by people who conveniently didn’t exist anymore, I reacted with defensive discernment toward those who celebrated the likes of Martin Luther King Jr. or the Civil Rights Movement.

Rick Pidcock

Maybe these months could remind us not to be racist. But they were tools in the hands of liberals to promote the Democrats and to promote theological liberals. However, we couldn’t simply reject Black people altogether like we did LGBTQ people. So we had to have discernment in order to defend against the dangers of Black History Month without being racist.

When it came to other religious holidays like Hanukkah, Kwanzaa or Ramadan, my body’s initial response was one of despair. These people were lost, dying on their way to “a Christless eternity,” we’d say. So any images or videos of their culture’s celebrations could be overlayed in our minds with a soundtrack of sadness.

Even though I’ve evolved to a progressive spirituality, that doesn’t mean I’ve converted to another religion. I’m not going to do a 30-day Ramadan fast or put up candles during December. And while I have experienced abuse, I don’t know what it’s like to be Black or an LGBTQ person in the United States today.

But my posture toward LGBTQ people, abuse survivors, Black people and followers of other religions when these justice-themed months are celebrated has fundamentally changed.

Learning of others and trusting them

The experience of separation and skepticism toward our neighbors is one that goes far beyond my fundamentalist past. As wars rage around the world and religious hierarchies posture for political supremacy, the personal exile I felt from my neighbors is being felt on large scale, national levels.

But despite nation rising against nation, there are glimpses of communities overcoming their fears and coming together.

One example comes from what many would consider a most unlikely place, the United Arab Emirates. UAE President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan gave 27 acres of land to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to build a Hindu temple in the Muslim country. Featuring motifs from both countries, the temple is being hailed as “a syncretic story of Indian and Arab civilization and values” that not only allows each culture to maintain its unique perspectives but also celebrates “one set of universal spiritual values.”

While the temple primarily brings together Hindu and Muslim communities, its chief architect was a Christian, and the project’s leadership included Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Zoroastrians and atheists.

“Its story will teach those around the world how by learning of others and trusting them, we can come together and not drift apart.”

Yogi Trivedi, a Hindu scholar, said: “Its story will teach those around the world how by learning of others and trusting them, we can come together and not drift apart.”

Dare to be silent together

In order to learn from others with a posture of trust, we have to dare to be silent with them. The fundamentalist impulses of defiance, deflection, discernment and despair are all indicative of a noisy soul. And to be fair to fundamentalists, if justice is violent retribution, then the noise of war is necessary.

But as long as the air is filled with the sounds of our warring words, we’ll never get to know one another, let alone have any kind of meaningful dialogue.

In The Inward Journey, Howard Thurman quoted playwright Maurice Maeterlinck, saying: “We do not know each other yet, we have not dared to be silent together.”

Thurman reflects: “It is no small wonder that man tends to worship the sound of his voice and to give it an authority greater than anything that remains when all words have been said. … Silence is not trusted.”

Despite our fundamental urge to fill the air with the noise of our words, Thurman reminds us, “It is out of the silence that all sounds come; it is in the stillness that the word is fashioned for the meaning it conveys.”

Then Thurman once again quotes Maeterlinck: “If it be indeed your desire to give yourself over to another, be silent.”

Sitting in the shade of another tree

It’s one thing to read news stories about distant nations giving land away for other religions to build multimillion dollar temples. But what can we do?

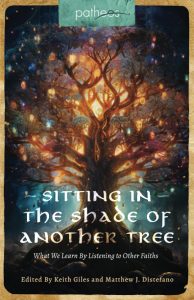

In their recent book, Sitting in the Shade of Another Tree: What We Learn by Listening to Other Faiths, Matthew Distefano and Keith Giles have compiled a series of essays from people with different religious backgrounds who have engaged in the practice of sitting in silence together and learning to listen to others with a posture of trust.

In their recent book, Sitting in the Shade of Another Tree: What We Learn by Listening to Other Faiths, Matthew Distefano and Keith Giles have compiled a series of essays from people with different religious backgrounds who have engaged in the practice of sitting in silence together and learning to listen to others with a posture of trust.

Yet to embody this posture toward neighbors requires a very different Christianity than the fundamentalisms of our past.

“When I say ‘Christianity,’ I’m not talking about a rigid, fundamentalist version of the faith,” Distefano says. “Instead, when I say ‘Christian,’ I mean a robust, mystical, spiritually driven one — the type of Christianity practiced by Fr. Richard Rohr, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Teresa of Avila, and Brother Lawrence.”

Listening to other traditions through technology

Even though we may never visit a Hindu temple in a Muslim country on the other side of the world, and even though we may never convert to another religion, there are experiences and languages of union and becoming that are common throughout a variety of religious traditions when we listen to their poets and mystics. And these voices can be brought to us through technology.

Heather Hamilton, one of the contributors for Sitting in the Shade of Another Tree, recalls how the internet opened her to silent listening.

“The only enlightened friend I had was Google.”

“In the throes of the terror of the unknown, all I had at my disposal was the internet,” she explains. “The only enlightened friend I had was Google. I knew I couldn’t ask any of my church leaders. I knew they would have no idea what I was talking about. So, I asked my friend, Google, a lot. … My Googling led to finding commonality with others describing their processes of spiritual awakening.”

Brandon Andress, another contributor, shares a similar story about how technology shaped his experience with Islam. Growing up during the Persian Gulf War in the 1990s, Andress regretted, “My source of information was sensationalized news, which is the absolute worst way to learn about any faith or subject. The media’s biased reporting and propaganda on Islam were particularly prevalent, although I was naively unaware of neither at the time.”

He continues: “We cannot turn a blind eye to the profound and detrimental impact of how the news media conflated Islam with violence. In the pre-internet era, they selectively curated how rural America viewed Muslims worldwide and how we understood the religion. … For rural Americans with little exposure to Muslims, the generalizations and stereotypes only reinforced their negative views of Islam, causing even more fear, hatred and antipathy.”

Given how the news media was complicit in fostering fear of our Muslim neighbors for decades, what if the media could cultivate a quiet curiosity instead?

A new religious age of belonging

Sitting In the Shade of Another Tree brings together men and women from Islamic, Zen Buddhist, Bahai, Neopagan, Taoist, Roman Catholic and Jewish backgrounds to explore how their shared values foster meaningful relationships.

Ilia Delio, founder of the Center for Christogenesis, believes this interfaith posture of listening and creative engagement is the future of religion.

“We are in a new axial age brought about by mass media, communications and internet technology,” she writes. “This new axial age has been developing for several centuries, beginning with the rise of modern science. While the first axial period produced the self-reflective individual, the second axial period is marked by interrelatedness and global consciousness. The tribe is no longer the local community but the global community, which can now be accessed immediately via television, internet, satellite communication and travel. … People are becoming more aware of belonging to humanity as a whole and not to a specific group.”

Becoming more aware of belonging to humanity

Throughout each year, the Special Emphasis Observances recognized by presidential proclamation, executive orders, or law are:

- January — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

- February — African American History Month

- March — National Women’s History Month

- May — Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month

- June — Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Month

- June 19 — Juneteenth

- September 15 – October 15 — National Hispanic Heritage Month

- October — National Disability Employment Awareness Month

- November — National American Indian/Alaska Native Heritage Month

One can’t help but notice how each of these months celebrate and honor people who have been harmed by Christians. In our theologies of Christian supremacist hierarchy and exile, we told them they didn’t belong or they belonged only if they bent the knee to us.

So as the year unfolds, notice how your body responds to each of these months. If you find yourself, like I did for many years, responding with defiance or defensiveness, then perhaps your inner work needs to be quieting your soul until you can silently sit under the shade of another’s tree.

As we listen to the voices under the trees throughout the year, let’s honor each group while learning to recognize ourselves in their experiences, and thus begin to value their belonging in our common humanity. Let’s allow these months to remind us to follow the lead of Howard Thurman, repenting of the idolatry of our own voices and daring to be silent together.

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.