Within hours of its announcement, the new White House plan to forgive $10,000 to $20,000 per person in student loan debt became a theological dividing line as much as a political one.

Critics of the debt forgiveness initiative turned to Bible verses to make their case that it is irresponsible to let people off the hook for debt they willingly incurred.

Advocates of the debt forgiveness countered with other Bible verses to make their case that relieving people of crushing debt is entirely biblical.

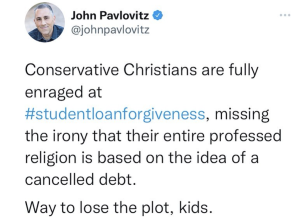

Ex-evangelical author John Pavlovitz commented on social media: “Conservative Christians are fully enraged at #studentloanforgiveness, missing the irony that their entire professed religion is based on the idea of a cancelled debt. Way to lose the plot, kids.”

Ex-evangelical author John Pavlovitz commented on social media: “Conservative Christians are fully enraged at #studentloanforgiveness, missing the irony that their entire professed religion is based on the idea of a cancelled debt. Way to lose the plot, kids.”

Response to this one statement encapsulates the hot divide that erupted among Christians over the student loan forgiveness program announced by President Joe Biden Aug. 24. Some people loved the Pavlovitz post, while others loathed it and challenged anyone who reposted it.

One person’s Facebook page

To illustrate, consider the 67 comments that accumulated on a friend’s Facebook page when she posted Pavlovitz’s statement. This friend is a graduate of a small Baptist university and has worked her entire career in higher education administration.

The first Bible verse quoted — eight comments in — was from the Parable of the Lost Son, with an argument made that the father welcomed the prodigal home and forgave him for all the inheritance he had squandered.

Not fair, one friend replied: “This suggests that the father paid the debt. However, this does not apply to our situation. Here the father is passing the bill on to the farm workers and then telling them that they should celebrate or he will consider them disloyal.”

“I would encourage you do a lot of research before posting over-simplified stuff like this that is misleading.”

Then another of my friend’s friends (that’s how Facebook works, right?) popped in with a stream of Bible verses to counter what Pavlovitz had said. And he began with a summary statement copied and pasted many other places on social media: “I would encourage you do a lot of research before posting over-simplified stuff like this that is misleading.”

The “over-simplified” and “misleading” item being Pavlovitz’s comparison of God’s cancellation of the debt of sin to the cancellation of college debt.

This person’s citations were:

- Romans 13:7-8 — “Pay to all what is owed to them: taxes to whom taxes are owed, revenue to whom revenue is owed, respect to whom respect is owed, honor to whom honor is owed. Owe no one anything, except to love each other, for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.”

- Psalms 37:21— “The wicked borrows but does not pay back, but the righteous is generous and gives.”

- Ecclesiastes 5:5 — “It is better that you should not vow than that you should vow and not pay.”

- Numbers 30:2 — “If a man vows a vow to the Lord, or swears an oath to bind himself by a pledge, he shall not break his word. He shall do according to all that proceeds out of his mouth.”

Then the friend closed with this: “I think you should rethink your stance instead of using salvation as a metaphor for a debt you pledged but have no intention of repaying.”

To that, another friend responded with Deuteronomy 15:1, Nehemiah 10:31, Ezekiel 18:7, Matthew 18:32 and Matthew 6:12 — all of which speak of God’s commands to forgive debts.

Another friend referenced Leviticus 25, where in the Old Testament law the Hebrews are mandated by God to observe a cycle of debt forgiveness every seven years, culminating every 50 years in a “year of jubilee” where debts are canceled and property reverts to its original owners.

‘This isn’t fair’

Then to the heart of the matter from one friend opposing the debt forgiveness: “Nothing is free. They are merely transferring the debt from one person to another. Are they going to reimburse me up to $20,000 or $10,000 in the $86,000 I paid? I took up my responsibility and paid it back, all of it. Where’s my compensation for that? If we’re going to do the fair and right thing let’s recognize all the sacrifices those made to pay it back. I had to leave my chosen industry, become a trucker, and many days eat ramen noodles to pay back my debt.”

“I took up my responsibility and paid it back, all of it. Where’s my compensation for that?”

Bible verses aside, the most common theme behind the Christians Against Debt Forgiveness campaign boils down to, “I paid off my loans, so it’s not fair for others to get off the hook. They should suffer like I did.”

Another example, this post: “We paid off our student loans. It was hard. It took a while. We didn’t go out to eat. We didn’t have nice cars. We sacrificed, started a family. Celebrated when they were paid off. I would like my $10k refund please.”

Variations on this argument proliferated across social media, often countered by another Bible verse, known as the Parable of the Laborers. In that story from Matthew 20, Jesus tells of a vineyard owner who hired laborers at different times of the day, some very late in the day, yet the owner paid them all the same wage. Those who had worked all day protested that this was unfair, but the owner explained he had not been unfair to them, he had paid them what was agreed. If he chose to be generous to others, wasn’t that his right?

Finally, at this point, my friend whose Facebook page was hosting this debate weighed in. Here’s what she said: “I get that I could be wrong about many things. However, I am ultimately accountable to God. When I face judgment, if God points out areas where I was wrong, I want to be able to say that I was wrong coming from a place of love rather than judgment. Grace, compassion, empathy and love drive my thinking and are the lenses through which I try to see others. Additionally, I have spent over 33 years working closely with college students. I can’t help but have compassion for the financial burdens that many of them have faced.”

“I have spent over 33 years working closely with college students. I can’t help but have compassion for the financial burdens that many of them have faced.”

If this argument sounds familiar, it should. The same argument that “I’d rather err on the side of love” often is used by Christians who are inclusive of LGBTQ persons in the church, as they acknowledge some Scriptures are disputed and Jesus said nothing about same-sex relations.

Meanwhile, a variation on the “it’s not fair” argument is the “you shouldn’t have done it” argument. Somehow that argument didn’t make the lengthy thread on my friend’s page, but it certainly showed up many other places, including in response to something I posted on my personal Facebook page.

“Students know the cost going in. It is also a fact that loans must be paid off at some point. … We have to make choices knowing the responsibilities attached to them,” one friend replied.

Real tuition rates

What prompted this was my sharing a graphic created by the Houston Chronicle showing this year’s in-state tuition rates for 28 Texas universities. The reason I posted it was that many people who graduated from college 50 years ago or who haven’t had kids in college recently have no idea how costs have escalated.

In less than 24 hours, my post drew 58 comments and 117 shares.

The chart shows this year’s annual tuition only — not including room and board and books and lab fees — ranging from $2,500 at some community colleges to $61,980 at Southern Methodist University. And lest you assume the Methodists are alone in eye-popping tuition, the Disciples of Christ and Baptists are not far behind. This year’s tuition at Texas Christian University is $53,980 and at Baylor University it is $51,938. Most of the big state schools fall in the $10,000 to $11,000 range.

One of the big differences between state schools and private schools is that at state schools the tuition is what it is, while tuition at private schools should be viewed like the rack rate at a hotel. While there are some students who pay full price at private schools because their families can afford it, most students at private universities benefit from generous scholarships that can cut the actual cost in half or more.

But half of $52,000 is still $26,000. Times four years, plus room and board.

Real stories

Our own two sons went to TCU a decade ago, both on full academic scholarships, which meant we paid no tuition — thank God. This would not have been possible otherwise. But we did pay — and are still paying — for the required room and board and other expenses of college life. At most schools, including state schools, that can rack up $10,000 to $20,000 per year, easily.

“Friends who have larger annual household incomes than ours or who benefit from trust funds often have no concept that the rest of us don’t enjoy the same benefits.”

We’re a typical upper-middle-class family, and we still had to make use of some student loans. One of the things I’ve noticed is that friends who have larger annual household incomes than ours or who benefit from trust funds often have no concept that the rest of us don’t enjoy the same benefits. Without malice, they simply assume if they can do it, others should be able to as well.

Many American families do not have the capacity to send their deserving children even to the lowest-priced state schools without taking out student loans.

And this is to say nothing of graduate theological education, which is worthy of a separate analysis. It costs just as much or more to earn a master of divinity degree as a law school degree or a combined master’s and doctorate in several other fields. Yet the lifetime earning capacity of pastors falls way below that of doctors and lawyers and bankers and engineers, making it virtually impossible for clergy to pay off the average $54,600 of student loan debt carried by master of divinity graduates.

This week, faced with news of the relatively small relief coming for student loans, some people began to share their own stories on social media, baring their personal financial details in hopes of convincing the skeptics that student debt is indeed a crisis.

For example, one man who had to take out loans to obtain his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees said he originally owed $89,000, payable at an interest rate of 6.8%. When he graduated, he owed the lender more than $1,000 per month and was not told there was an income-based forbearance option. To date, he has paid the lender more than $104,000 and still owes $84,000 — all from the original debt of $89,000.

“Some student loan programs become debt traps with no exit.”

Some student loan programs become debt traps with no exit. It’s not that the graduates aren’t paying on their loans; it’s that they never can get them paid off. That, in turn, discourages them from having children and buying houses.

How did we get here?

At root, the problem is the soaring cost of higher education compared to more stagnant wages in America.

One friend replied to my own Facebook post: “I still meet people who talk about how they worked summer jobs to pay for college back in the day, implying that kids these days should just do the same (or more of the same). If you’re making enough at a summer job to pay these tuition rates, you should just do that job. I admire people who put themselves through school that way. But the equation has changed, and it just doesn’t/cannot work that way anymore.”

That assertion is backed up by the data:

- Between 1980 and 2019, college fees rose by 169%, while wages for young workers ages 22 to 27 went up by 19% over the same period.

- The cost of college has doubled in the past two decades and is growing each year by 6.8%.

- The average cost to attend an in-state public school for one year is $25,487.

- Students attending private schools pay nearly twice as much, $53,217.

- 43 million student loan borrowers collectively owe around $1.6 trillion.

- Collective student debt increased by 144% over a 13-year period from 2007 to 2020, jumping from $642 billion to $1.57 trillion.

Armchair theologians and economists

Despite these undisputed facts, the current news about student loan forgiveness has empowered a horde of armchair theologians to quote Bible verses to justify their mainly political positions, often with little regard for other government incentives that are even more costly in the long run.

The 2017 changes in federal tax law signed by then-President Donald Trump cost the government $2 trillion and mainly benefited the top 1% of earners in the nation. By comparison, the projected cost of the student loan forgiveness is $244 billion, and the program will mainly benefit middle- and lower-income families.

Fiscal conservatives called the tax changes a “stimulus” but consider the loan forgiveness a “bailout.”

But what’s currently drawing the most attention on social media in the debate about student loans is a comparison to the Paycheck Protection Program of the recent pandemic years. That economic stimulus plan during the dark days of pandemic shutdowns cost the federal government nearly $800 billion — more than three times the cost of the student loan forgiveness.

“The Venn diagram of those who had PPP loans forgiven and those that are griping about student loan forgiveness is a circle.”

Defenders of student loan forgiveness like to point out that many of the critics of that forgiveness benefited from the PPP loans and didn’t see that as unfair. As one pastor pointed out via Twitter: “The Venn diagram of those who had PPP loans forgiven and those that are griping about student loan forgiveness is a circle.”

In the mashup of theology and politics, Bible-quoting Christians also became economics experts this week, some justifying their opposition to the debt forgiveness by insisting it will cause inflation in the U.S. economy. Real economists are divided on this question, however.

In a highly technical answer, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget — a nonpartisan group — said the debt cancellation is likely to increase inflation and is an ineffective way to stimulate the economy. That is because with supply and demand already tight due to supply chain issues caused by COVID and the war in Ukraine, giving people more money to spend will only increase the desire for the limited goods available, thereby increasing prices.

Others, however, said reducing student loan payments would not affect the economy in the same way as, say, handing out stimulus checks as was done in the first year of the pandemic.

“Whatever your view of student-debt cancellation, the inflation argument is a red herring and should not influence policy.”

Joseph E. Stiglitz, a professor at Columbia University and chief economist at the Roosevelt Institute, writing in The Atlantic said student loan debt forgiveness could actually reduce inflation: “Whatever your view of student-debt cancellation, the inflation argument is a red herring and should not influence policy. Taking that logic to the extreme, canceling food stamps would do far more to reduce inflation — but that would be cruel and inhumane, and fortunately, no one has suggested doing so. A closer look at the student-debt-cancellation program suggests that the new student-loan policy may even reduce inflation; at most, its inflationary impact will be minuscule, and the long-term benefits to the economy are likely to be significant.”

Bible verses and theology aside, reactions to the student loan forgiveness often fell along political lines — which in today’s American also means religious lines.

Yet amid this debate, one former Southern Baptist Convention leader rose above the political fray and took a victory lap for the SBC’s Cooperative Program unified budget, which deeply subsidizes tuition at all six SBC seminaries.

Morris Chapman, former president of the SBC Executive Committee, tweeted: “Praise God that NO Southern Baptist seminary graduate is indebted because of their ministry training at Southern Baptist seminaries. … Without the Cooperative Program, it is impossible to estimate the burden of debt our graduates would carry.”

Related articles:

Many ministers saddled with seminary debt

Cancel student loan debt for everyone | Opinion by Brittini Palmer

Providing ‘a hand up’ to ministers struggling with credit card, student loan debt