One of the biggest trends in entertainment today is true crime dramas about serial killers. Forbes reported in 2020 that it was a “great year for fictional serial killers.” And now, two years later, our fascination with mass murder is continuing, but with a focus on true stories.

Apple TV’s Black Bird tells the story of Jimmy Keene, who was imprisoned for drugs and worked with the FBI to earn the trust of Larry Hall, who was believed to have murdered 20 young girls.

Although not a show about a serial killer, The Watcher on Netflix is a true crime mystery based on a story that was published in New York Magazine in 2018 about a family who purchased their dream house and began receiving threatening letters from a stranger.

Another true crime drama that has been climbing the charts has been the Netflix series Dahmer — Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. Dahmer already has become Netflix’s “second most popular English-language series of all time … in just its third week of eligibility,” passing such popular shows as Bridgerton. With 3.7 billion minutes viewed in just one week, it was the No. 1 show according to Nielsen’s rankings of original streaming shows, including “the chart’s 10th-biggest tally ever in its 110-week history.”

Dahmer explores the true story of how Jeffery Dahmer murdered 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991. In addition to murdering his victims, he also committed necrophilia and cannibalism. But despite the deeply disturbing nature of his case, it was determined he was legally sane. Dahmer was sentenced to 16 life terms but died in November 1994 from being beaten in prison by another inmate.

Why we watch serial killers

According to polling data by Morning Consult, 62% of adults in the U.S., including almost 80% of Millennials, say they are casual to avid fans of shows or movies about serial killers.

The reasons for watching content about serial killers varies. When asked what the major reason was for watching, respondents said:

- The psychology of the serial killer (58%)

- The suspense (48%)

- They help me feel more informed about the world (34%)

- They are scary (27%)

- The violence (20%)

When adding together the major and minor reasons for watching serial killer content, Morning Consult noted that “89% said ‘the psychology of the serial killer’ is a reason they find the content interesting, while 84% cited ‘the suspense’ as a reason. According to experts, many viewers are drawn to this type of content because it serves as a form of escapism, or due to the adrenaline rush it provides.”

Their research also found: “About seven in 10 U.S. adults (72%) said they find content about serial killers interesting because it helps them feel more informed about the world. Morning Consult data found that more than half of U.S. adults (52%) said it is appropriate to learn about serial killers by watching a fictionalized TV show or movie about their life.”

Telling true crime stories through entertainment

While there are a variety of reasons we watch true crime stories, there are also a variety of reasons why they are produced and written. And the decisions that are made during production have real consequences for everyone involved in the process and who have been affected by the crimes.

Ryan Murphy, who created both Dahmer and The Watcher, said his reason for creating Dahmer was to raise awareness on who Dahmer’s victims were and to emphasize how many of them were gay Black men.

Of course, any show that is produced has to be concerned about ratings and about telling an artistically compelling and coherent story.

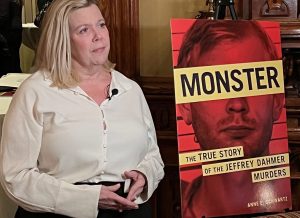

Anne E Schwartz with a poster for her book about the Dahmer murders.

In 1991, journalist Anne E Schwartz, who was working as a crime reporter for the Milwaukee Journal, was contacted by the police regarding a human head and various body parts they had discovered in an apartment. In an interview with The Independent, Schwartz said that due to the “artistic license” that was taken, the Dahmer series “does not bear a great deal of resemblance to the facts of the case.”

According to Schwartz, the odors coming from Dahmer’s apartment smelled like chemicals rather than bodies, the police officers were not racist and homophobic, and Glenda Cleveland lived in a separate building, rather than in the next-door apartment.

Additional differences include combining characters’ stories, having Dahmer wear his glasses during the trial even though he intentionally chose not to so that he wouldn’t see people and panic, depicting his father teaching Dahmer how to dissect roadkill when all he really did was teach him how to preserve animal bones, showing sounds of power tools coming from Dahmer’s apartment when in reality all his neighbors heard was music, and making Dahmer’s neighbors appear to be suspicious of him when they actually thought he was a friendly, introverted geek who they would occasionally have a beer with.

A clash of perspectives

Because 89% of U.S. adults indicated that the No. 1 reason they watch shows about serial killers is that they want to learn about the psychology of the serial killer, show producers have to focus on getting into the minds of the murderers.

In Dahmer’s case, the series explores his troubled childhood — including an absent, drug-addicted and suicidal mother, an absent, work-focused father, and a history of being misunderstood or bullied at school. It also delves into his struggle to process his sexuality and even frames his cannibalism as an expression of his sexuality.

“One of the most common criticisms of the series has been that it doesn’t focus on the perspectives of the victims enough.”

Another perspective the series explores is the perspective of the victims. Episode six in particular focuses on Tony Hughes, who was a deaf man Dahmer murdered. Much of the episode plays with muffled sounds to help the viewer identify with the experiences of Hughes. Yet one of the most common criticisms of the series has been that it doesn’t focus on the perspectives of the victims enough, as demonstrated in the final scene of episode six bringing the attention back to Dahmer rather than commemorating Hughes.

More perspectives come from the family members of those involved. On one hand, the series shows the deep regret, fear, anger and love Dahmer’s parents had. No parent could begin to imagine what would go through your heart and mind if your child committed the crimes Dahmer committed. Watching his parents wrestle with their regret is heart-wrenching.

On the other hand, it has received criticism for how it handled the perspectives of the victim’s family members. Rita Isbell is the sister of one of the men Dahmer murdered. She was depicted in the show for her victim impact statement that she gave during court.

On the other hand, it has received criticism for how it handled the perspectives of the victim’s family members. Rita Isbell is the sister of one of the men Dahmer murdered. She was depicted in the show for her victim impact statement that she gave during court.

In an interview with Insider, Isbell said: “When I saw some of the show, it bothered me, especially when I saw myself — when I saw my name come across the screen and this lady saying verbatim exactly what I said. If I didn’t know any better, I would’ve thought it was me. Her hair was like mine, she had on the same clothes. That’s why it felt like reliving it all over again. It brought back all the emotions I was feeling back then. I was never contacted about the show. I feel like Netflix should’ve asked if we mind or how we felt about making it. They didn’t ask me anything. They just did it.”

Even those who participated in creating the show had a variety of perspectives.

Kim Alsup, who was a production assistant, tweeted that she was “treated horribly” during the creation of the show, even calling it “one of the worst shows” she’s ever participated in. “I worked on this project and I was 1 of 2 Black people on the crew and they kept calling me her name.”

She added, “We both had braids. She was dark skin and 5’10. I’m 5’5. Working on this took everything I had as I was treated horribly. I look at the Black female lead differently now too.” She told the Los Angeles Times, “I was always being called someone else’s name, the only other Black girl who looked nothing like me, and I learned the names for 300 background extras.”

Then there is the perspective of shame felt by the broader community of Milwaukee. Schwartz said Milwaukee is “absolutely done with hearing about the case. People in Milwaukee think this is a horrible blemish on the city, they don’t want people to think about it.”

Other broader communities also were affected by the show. The LGBTQ community has been reminded of how they have been violently targeted. And many in the LBGTQ community were hurt when Netflix labeled the show as an “LGBTQ series,” before removing the tag after receiving backlash.

“The themes in Dahmer reach all the way into the most complex hierarchies and exiles we’re facing today.”

With the questions today surrounding violence against LGBTQ and Black communities, especially by the police, the complexity of perspectives goes beyond the murderer, the victims, the families, the show creators and the community. The themes in Dahmer reach all the way into the most complex hierarchies and exiles we’re facing today.

Cheap grace

In the final episode of the series —titled “God of Forgiveness, God of Vengeance” — the writers explore what should happen to Dahmer in order to bring justice. The conversations throughout the rest of this article are likely dramatizations created by the writers of the show. My sharing them here speaks nothing to their authenticity. It is simply to explore the themes of grace and justice the final episode delves into.

One of the unexpected twists is conversations about the nature of grace, as a result of Dahmer becoming a Christian and being baptized. In one scene, Dahmer talks to a priest about another convicted murderer who became a Christian. Dahmer says: “I wanted the death penalty. And he was saying that he’s not afraid to die because he’s made his peace with God and he’s going to go to heaven. So I guess my question is: Do you think God’s forgiven him for all that?” Later in the conversation, he says, “I don’t think I deserve forgiveness for what I’ve done.”

The priest responds, “It’s not about ‘deserve,’ Jeff. That’s the thing about grace. We don’t deserve it, but we get it anyway.” Then as the priest reminds Dahmer of the two thieves on the Cross, the priest says regarding the thief on the right, “Jesus didn’t ask him what he’d done to be crucified, didn’t ask him if he was sorry. All this guy had to do to be saved was to believe that Jesus was the Son of God.”

The priest responds, “It’s not about ‘deserve,’ Jeff. That’s the thing about grace. We don’t deserve it, but we get it anyway.” Then as the priest reminds Dahmer of the two thieves on the Cross, the priest says regarding the thief on the right, “Jesus didn’t ask him what he’d done to be crucified, didn’t ask him if he was sorry. All this guy had to do to be saved was to believe that Jesus was the Son of God.”

Later, when Dahmer is baptized, the priest says, “Welcome to the family of God! Congratulations, Jeff. You’re saved!”

But is that justice? Does it make things right for God to overlook Dahmer’s murder, necrophilia and cannibalism simply because Dahmer believed Jesus is the Son of God and got dunked under water momentarily?

Does that make things right for Dahmer, the victims, the families, the show creators and the communities who experienced a spectrum of exile due to the violence Dahmer perpetrated?

If we’re honest with ourselves, more has to be done than merely saying a prayer, getting wet and moving on.

Retributive justice

The more immediate and understandable response to Dahmer’s crimes was a cry for retribution.

Referring to another murderer, one character says, “That man’s going to burn in hell, and not fast enough.” Then they discuss if Dahmer deserved hell more.

In one of the most difficult scenes of the series, one character says to another priest: “What you said in your closing prayer today about forgiveness, showing mercy, now I know it’s the Christian thing to do. We all have fallen short. And at some point or another we all deserve grace. But when it comes to Jeff Dahmer, I can’t forgive him. Even though there may be something wrong with his brain … my heart is full of hate, revenge. I thought him being in jail for the rest of his life would be enough. It’s not. I want to see him suffer. I even have nightmares about it. And I see myself hurting him, giving him pain, making him beg for mercy. I’m scared, pastor. I’m so scared. I just wish I could get past these feelings. You know? That I could stop living in vengeance. That I could get to a better place. Maybe, I don’t know, maybe not forgiveness, but something close to it? ’Cause if I keep letting hate and anger consume me, I’m not gonna know myself no more.”

“How do our theologies of retribution make things right?”

While the call for retribution is totally understandable from the perspectives of those who have been hurt by violence, the question Christians need to ask is this: How do our theologies of retribution make things right?

Does eternal conscious torment of Dahmer make things right for the victims or their families? Does it solve all of the complexities discussed earlier in this article for all the communities involved?

Does annihilationism fare any better at making things right? Does it bring back the victims, and then heal their bodies, minds and hearts?

Of course, retribution to some extent makes sense for the victims. But it doesn’t actually make anything new for the victims.

Restorative justice

No matter how much comfort Christians draw from theologies of heaven, there is no way to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt what happens in the afterlife. So perhaps we’ll all die and lose our consciousness without anything being made right.

“The theologies of eternal conscious torment and annihilationism present an end where very little if anything is restored among all the complexities of pain.”

As it stands, the theologies of eternal conscious torment and annihilationism present an end where very little if anything is restored among all the complexities of pain.

But what if there is a possibility that there is a God who is “making everything new?” What if there is a tree whose leaves are “for the healing of the nations?”

What would that look like?

It wouldn’t be cheap grace. It would make Jeffery Dahmer fall prostrate before his victims and God. It would invest the eons of time that may be necessary to do the inner work of softening and making new Dahmer’s dark soul. For Dahmer, that would be hell.

It wouldn’t be a dead end of retribution.

It would lift the faces of Dahmer’s parents and help them grieve through the regret and love they have for their lost son.

It would bring resurrection to his victims, walking with them through their traumas and healing every wound.

It would restore them to the arms of their families until all they know is a love that runs deeper than bone.

It would demonstrate that the entire universe is a community of communities, that to break one community is to break them all.

Erasing the victims or loving all

In one heartbreaking scene, the character of Dahmer’s dad stands over his son’s dead body and breaks down. “I love you. I’ve loved you since the day you were born,” he speaks, trembling. “And I’ll love you ’til the day I die.”

In another, a character inquires about what will happen to the property where Dahmer committed his crimes. She says, “Y’all demolished the building, but that doesn’t erase what happened. It only erases the victims.” And when she doesn’t get the answer she’s looking for, she says, “As long as I have breath, I’ll keep waiting.”

We can’t simply forgive and forget what Dahmer did.

Maybe there will be no justice as the cosmos dies. But if there is a way to make things right, the only way it will is if it reaches into the darkest depths and farthest exiles of every single community in the cosmos and makes all things new.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.