Gladstone’s Library is a remarkable institution, a residential research library in Northern Wales that was founded by four-time British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. Last month, I taught a course at the Library with Oxford University’s Professor of Black Theology Anthony Reddie, and afterward I interviewed the library’s warden, Andrea Russell, about the Library, Mr. Gladstone, faith and politics. Russell is an Anglican priest, a former lawyer and a scholar of the Anglican theologian Richard Hooker. I’m so grateful both for her invitation to engage big questions at the Library and for her response to these questions over dinner.

Greg Garrett: Could you tell us about the ethos of Gladstone’s Library?

Andrea Russell

Andrea Russell: I think the ethos has to do with the ever-widening circle of people who would be welcome here. So the idea that this is going to be a place where people gather, it’s the center for learning, but learning isn’t necessarily just with your head in a book.

There’s a sort of prayer that I use in chapel which talks about this as a place of study and rest, of learning and reflection, of silence and conversation. And I think the ethos is that holistic understanding of learning. You can come here whether you are a Baylor professor or whether you have perhaps not lots of formal education but you are a curious person and you want to know more. So, a place of welcome and learning.

GG: Why do you think Mr. Gladstone might be pertinent to us in 2024?

AR: One thing that really intrigues me about him is he’s a man who wasn’t afraid to change his mind. He comes from a very sort of low-church evangelical family through his mother. He ends up his life as high church and Catholic. There’s a quote we have in the chapel, the one that says he is a deeply committed Christian man, but you can tell by the way he’s talking that he wants to be open to what other people think.

The second thing is you see the books he brought to begin the library. He wanted it to be a place of divine learning, but they’re not all about the Bible and theology. There’s a book in there on witchcraft, and he’s interested in history and politics and classical literature. Even in his day, he has this idea that if you want to be a good clergyman you need to see what God is up to in the world, not simply in the small narrow field of theology and the Bible, you would be forever reading the world and the Scriptures through each other.

He intrigues me because he’s a man who is widely read. He reads people he absolutely disagrees with and he writes these notes in the margin, but he wants to engage with them.

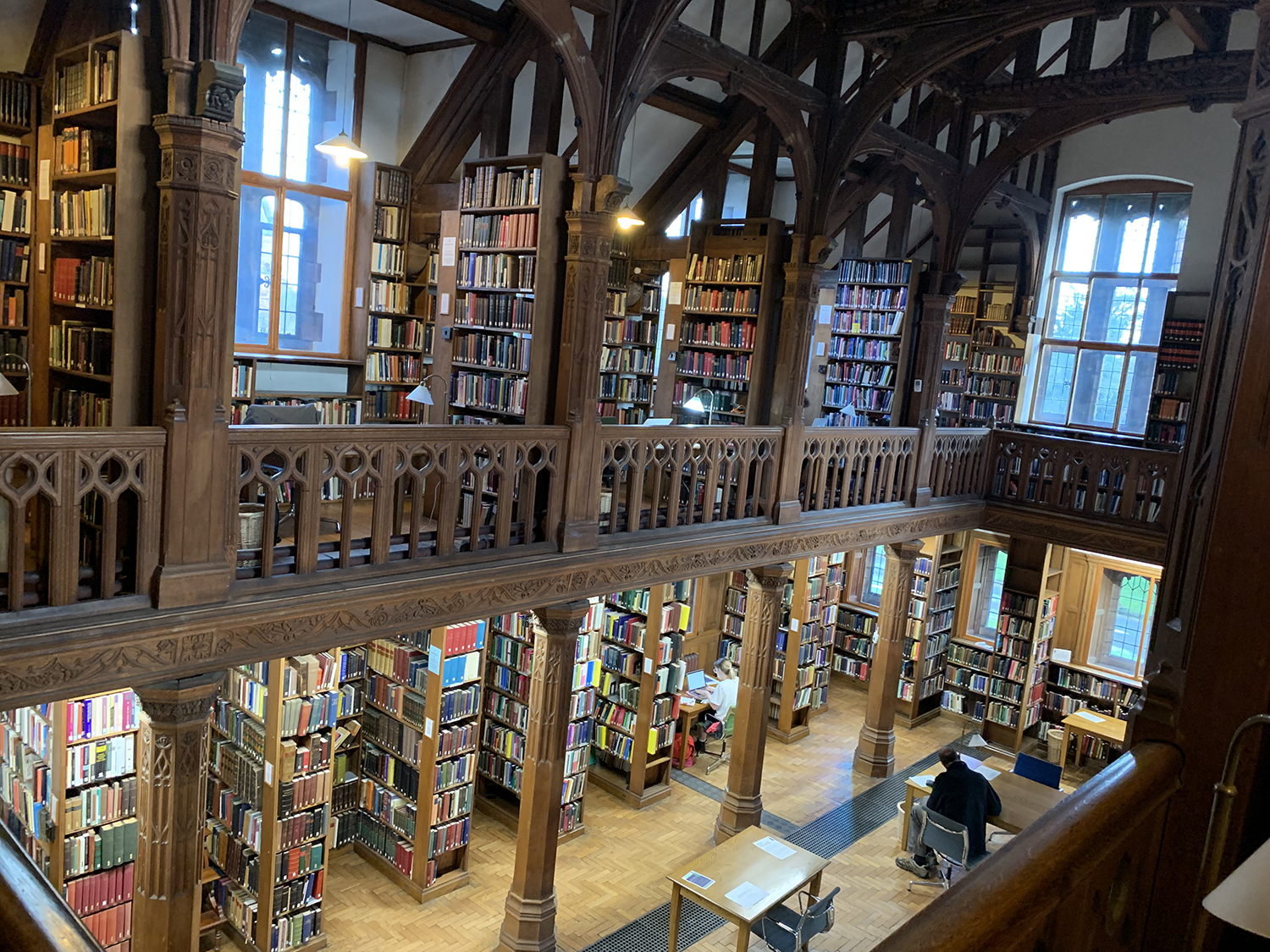

Interior of Gladstone’s Library (BNG photo by Mark Wingfield)

GG: That leads directly to the idea of the Library as a place of conversation between people who might not agree with each other. You’ve spoken about the difference between conversation and debate. And in the States and here we have very serious cultural divides. How does a place like Gladstone’s invite people into conversation that doesn’t close off possibilities and doesn’t close off relationships?

AR: I think it’s hard. I remember soon after coming here starting to talk about the difference between conversation and debate. In our schools, we’re taught you are successful if you can persuade, if you can get the vote at the end. And so what? You’ve done a clever — I’m an ex-lawyer — you’ve done a clever argument. I could argue you into a corner. That’s great, but who’s benefited from that? I don’t know.

And so, the idea of conversation being something that creates a third space so there must be a sort of initial consent from both of you that you’re going to dare to do this together, and it can be quite tentative. At Gladstone’s, this happens formally in the courses we have, so we try to build in with the leaders of those that there will always be time for conversation. When we have courses and events, we make sure there is that space for people to be able to not just share their comments but to actually enter into a conversation, which is what we did with your course this weekend.

“We make sure there is that space for people to be able to not just share their comments but to actually enter into a conversation.”

I think it also happens informally, in trying to say conversation does need to be something you enter into voluntarily. After chapel, I often come and sit with people and have my coffee while they’re having their breakfast. And you start to have a gentle conversation and you allow each other to lead the way in some ways.

And the great thing here is that then the next morning, if I’m having a conversation with somebody else and they say something, I can say, “You would really find Jean over there very interesting. And would you mind if I introduced you?” And so building relationships that mean people might feel safe enough to start to share some things. That is what we’re trying to do.

GG: In our course this weekend, one of the core themes that grew out of our conversation was the simple fact of “us” and “them,” the tribal thing. Sometimes it’s about race and sometimes it’s about other forms of our identity. One of the things I admire about Mr. Gladstone is that he was a person who had compassion for people who were not the “us” he understood. The passion he had around human rights and the posters out there of Gladstone’s words about how this place where we stand is not a British place, it’s not a Christian place, it’s a human place. I have preached that. What are some of the other things you hope we could learn from him?

AR: One of the foremost things is that he continues to learn throughout his life. So learning isn’t something that happened back then and now he’s putting it into practice. He’s still learning, he’s still questioning, he’s still wanting to read. He used to lend his books to everyone and then he’d ask you what you thought of it. So you’re like, “Oh my goodness, he’s given me a book again. I’m going to have stop tonight and read it.”

His library at the castle was called the Temple of Peace. People spoke as if Gladstone went into his library in order to escape the world, that this was his retreat, but I think he went in there to engage the world. You can’t help but think about Jesus talking about “my peace I give you, not in the way that the world gives,” because I think these books really stood him up. He’s constantly engaging, wanting to know what other people think.

“Wendell Berry basically got me through lockdown.”

GG: Where are you finding joy and peace personally, professionally?

AR: I think just personally is my family. I’ve got two daughters. I’ve got a brand-new grandson.

Here in chapel in the morning, we use poetry as well as liturgy as well as reading the Gospel. People like Mary Oliver, Wendell Berry, people who remind you of the beauty of the world. Wendell Berry basically got me through lockdown. When you hear those words being spoken alongside the Gospels, that is one bit that sort of holds me in there.

The quality of silence, the fact that the chapel is available. I’m an Anglican priest, but when we have somebody who’s a different faith or no faith at all and they find a space in that chapel, then it makes me think, yeah, there’s some hope for the world.

Being in an environment where learning is seen as being a norm, where asking questions of yourself, of others, of the books you’re reading isn’t seen as being odd. People who want to talk about what they’re studying gives me real hope. There are times when you think, my goodness me, I don’t know what we make of any of this, but that there are people here who want to genuinely have conversations with people who they would not necessarily agree with, that all gives me hope.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University, where he is the Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of 30 books, most recently the novel Bastille Day and The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us about Life, Love, and Identity. He is currently administering a major research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and finishing a book on racist mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Honorary Canon Theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Michael Curry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Melissa Deckman

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Matthew D. Taylor

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Nancy French

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Robert P. Jones

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Brian Kaylor

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Colin Allred

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Tia Levings

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Linda Livingstone

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Samuel Perry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jimi Calhoun

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with David Dark

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Randolph Hollerith

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jillian Mason Shannon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Vann Newkirk II

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Sarah McCammon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong