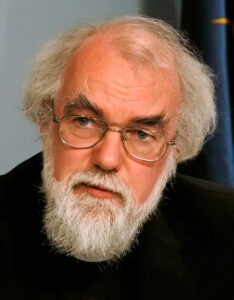

Rowan Williams is the past Archbishop of Canterbury, the retired master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, and one of the world’s greatest living theologians. He is also a person who has thought concretely about social issues, governance and government over the years, whether in the House of Lords or, most recently, in connection with his work co-chairing the Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales. I sat down with Lord Williams in his study in Cardiff for a long conversation about politics, faith and diversity. I am so pleased to share part of it with you.

Greg Garrett: Rowan, you have recently given major public lectures around the idea of solidarity. I wonder if for my readers you could summarize the conclusions you reached about solidarity and why they might be useful for us in our present moment.

Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams: Thanks, Greg. The project really originates by the question of why solidarity as a virtue or a value appears so prominently, especially in Catholic social teaching. John Paul II said the marks of a healthy democratic society would be dignity, subsidiarity and solidarity, that is, respect for human beings as having the capacity to make decisions in a complex society, but above all solidarity as a sense of fundamental shared interest between people in a community.

When you start with fundamental shared interest, what you’re saying is basically what’s good for me and what’s good for you have to converge at some point. I can’t have what’s good for me at the expense of what’s good for you because your deprivation at the end of the day is my deprivation.

Speaking as a Christian, I see that as a version of what Paul talks about in the first letter to the Corinthians: If one part of the body suffers, every part suffers. I don’t say simply my little finger has a cut, I say I have a cut in my little finger, I have a cut. So similarly, it’s not that some people suffer economic deprivation, it’s that I suffer economic deprivation through the misery of my neighbor, and therefore part of my own self-care is the care of my neighbor.

GG: This has incredible value for Americans. We are individualists, our great stories are about radical individuals, an ongoing rhetorical strain that pushes back against solidarity argues we succeed or fail individually. But it strikes me that what we do have that is similar in both of our nations is that there is solidarity within groups, but it has transformed us into “us” and “them” groups. What I hear you saying is that we have to recognize our common humanity, the ways we’re more alike than different.

RW: The ways we’re more alike and the crises that face all of us, whether we like it or not: we’re all going to die. Humanity 101, we’re all going to die. We’re all fragile. Our health and our material security are uncertain. We live in a world where whatever story you tell about the climate crisis, there is a climate crisis. We live in a world where pandemics jump frontiers. I’ve often said crises don’t read maps. We live in a world where the instability and vulnerability of certain regions and certain nations produces a huge challenge for other nations in the form of migration.

“We live in a world where whatever story you tell about the climate crisis, there is a climate crisis.”

The important challenges we face are challenges that we have in common. Meanwhile, as you say, we run for the corners of the room. We mythologize and demonize our opponents. We work on the assumption that the person who disagrees with me is not only wrong but wicked, and we leave ourselves no room at all for negotiating about our common challenges.

And that’s what worries me most. We treat the political opponent not just as somebody who is perhaps fatally wrong about things, but as somebody who is morally unrecognizable. And at the extreme of that, you have the sort of QAnon mythology: my opponents are diabolical shape-shifting pedophile cannibals. And you don’t say, well, they’ve got to get their children to school in the morning as well, and they’ve got to do the shopping on Saturdays.

How do you haul back toward that recognition that the other person is not a shapeshifting cannibal, but somebody who’s got to get the kids to school, and who therefore has some investment in, oh, I don’t know, clean air, safe roads, good schools?

I think, maybe unfashionably, that the religious dimension in all this is actually getting us back down to earth. We believe, as Christians, certainly in incarnation, we believe that as somebody said, God so loved the world that he did not send a committee or a mission statement. There’s a face-to-face involvement baked in.

And that’s emphatically true of the Jewish tradition and Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist traditions too. They really are about how you conduct yourself here and now in the presence of other embodied human beings.

So if the church and other religious bodies have anything to say in the political realm, I would want to suggest that, more and more, is what we ought to be talking about.

GG: I’m very concerned with white Christian nationalism, so-called.

RW: That is something very unrepresentative of the huge majority of the Christian tradition. Christians have at various points identified quite strongly with national political establishments for a variety of reasons. But the idea of chosen nationhood is precisely what I think the first Christians are trying to riddle out of and get away from.

“The idea of chosen nationhood is precisely what I think the first Christians are trying to riddle out of and get away from.”

Sometimes that appears in the form of the poisonous antisemitism that has distorted so much of Christianity. But at its best, it is saying the will and purpose of God is not identical with this or that government or this or that ethnic group. And liberty, if we want to talk about liberty, is not just about individual liberty, but the community’s liberty to be what it needs to be without local power and ethnic identity; that’s the liberty I think religious belief brings into the conversation.

GG: Something that doesn’t happen enough in either of our countries is contact between people who differ from each other radically. I was celebrating with you how my classes at Baylor bring together people from across the political spectrum, people from a number of sexual identities, and what I love to watch is just their sitting in the same room and growing to appreciate their humanity.

RW: If you’re in a room breathing the same air, eating the same cheap biscuits, don’t knock it. It’s an important part of social brokerage. Something comes through. It’s harder to believe that somebody is a shapeshifting cannibal if you’re eating bad biscuits together.

And I think that’s an essential bit of what we all need. I was thinking too, when you get to genuinely difficult and potentially traumatic conversations where there’s deep historic hurt on both sides, you also need a certain amount of, what should I say, safety netting. You need people to know that they’re safe.

And I know that there are some who sneer at the language about safe spaces, but actually when you’ve sat with somebody who’s experienced what an unsafe space is like, you’re less inclined to dismiss it. It hurts. And I was thinking there of an event a few years ago, connected with a little charity I was involved in founding called Inspire Dialogue, and we marketed ourselves in a small way as a network in which difficult conversations could be managed.

“When you’ve sat with somebody who’s experienced what an unsafe space is like, you’re less inclined to dismiss it.”

On one occasion we had a conversation between two people from Rwanda about the Rwandan genocide. One of them was the daughter of one of the generals who had overseen several massacres. The other was a man who most of his family had been butchered in the genocide. Now to prepare that needed quite a lot of thought and work. Both those people needed to speak to other people before they could talk to each other. They needed to know they had the option to pull out and so on.

By the time we actually got to the event where these two sat in front of an audience and spoke about their experiences, they had enough anchorage, enough sense that there were people holding them up from behind, not to back off from each other.

Let’s not suppose there’s a magic bullet here in which face-to-face conversation solves everything, because it can make things worse, but prepare it, think about it, find out where the wounds are and where therefore you have to tread very carefully.

As I say that, I think of a very important phrase I came across in the writing of the British fantasy novelist Alan Garner, who talked about his encounters with his therapist.

And the therapist’s maxim: “Go where it hurts most.” But to go where it hurts most, you would need to have built up quite a support system. That’s emphatically true if you’re trying to bring together people whose disagreement is not simply theoretical, but somehow existential.

Thinking back to the trans question and how you broker a conversation between let’s say a woman who has been raped or assaulted, perhaps in some public place, and a trans woman who is recovering from suicide attempts. They’re both at risk, so forget the theory for a moment. They’re both at risk. There’s your agenda. How do you cope with their sense of being at risk? How do you give them sufficient, what I call anchorage, to make it possible to let that encounter be something other than destructive? It’s a big ask.

GG: The great Black preacher Ralph Douglas West sometimes talks about how important it is for people to see the two of us working together, loving each other, and to realize that these boundaries, the “us” and “them,” can be broken. It seems to me that, because of the space I occupy, I have to be a generating force, I have to reach across and outside the boundaries of my “us.” Is there anything in the solidarity work or in our tradition that talks about why people like you and me need to be the people to risk?

RW: It’s a good way of phrasing it, I think. Many years ago, I spoke with a white priest of English origin in South Africa there in the bad old days of apartheid. We were talking about what it meant for a white priest to be in solidarity with the African population. He said the only thing that really made sense to him was you have to share the risk.

“If you’re serious about solidarity, you have to be vulnerable.”

If you’re serious about solidarity, you have to be vulnerable. You can’t just say from a distance, I know how you feel, or I think it’s really terrible, and then disappear. To say that you voluntarily accept a risk that somebody else has no choice about, that’s something which the privileged can do in some ways and is important for them to do. Just as it’s important for the privileged to say to the not so privileged, you set the pace here, because I don’t want this to be just another instance of my coming in and telling you what you need.

GG: One of the things I’ve been asking everyone, and this is where I’d like to finish, I always like to finish on hope. It seems to be a good holy model. Where, as you look at the world, as you look at your life, are you finding hope for the future?

RW: A lot of it, as you might perhaps guess from what I’ve been saying so far, is very, very local, very small scale. I’m always immensely heartened and enriched by spending time with school students from 4 years old onward. And that I’m a grandparent, of course, that also gives me hope and keeps me alive.

Because I am still going to schools to take services and do talks from time to time, I find that level of possibility is real in the faces and the eyes of young children, I find that always irresistibly hopeful.

And while there’s ample confusion about this, if you scroll forward a few years into the teens, there remains the fact that people, human beings, are growing up all the time without having their minds yet made up. And let’s just bear in mind that is an important fact about human beings. There are human beings around us whose minds are not yet made up.

So that helps. And in the same kind of spirit, I find increasing levels of involvement just in local parish ministry and sharing prayers and ministry with people in this part of Cardiff that really is life-giving for me. I learn in that case very often from people at the other end of life who have been faithful for decades and who are still there. And I know they have learned, they have made up their minds, but it hasn’t shrunk them or dehumanized them.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

More from this series:

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Nathaniel Jung-Chul Lee

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Starlette Thomas

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Samuel Perry

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jimi Calhoun

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with David Dark

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Randolph Hollerith

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jillian Mason Shannon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Vann Newkirk II

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Sarah McCammon

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Winnie Varghese

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Kaitlyn Schiess

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Russell Moore

Politics, faith and mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Politics, faith and mission: A talk with Tim Alberta on his book and faith journey

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jemar Tisby

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Leonard Hamlin Sr.

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Ty Seidule

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Jessica Wai-Fong Wong

Politics, faith and mission: A conversation with Brian McLaren