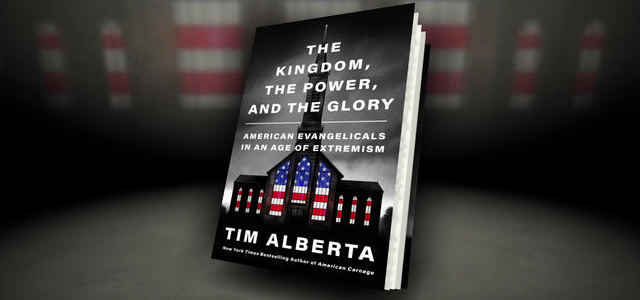

You may have watched Tim Alberta recently on 60 Minutes, Meet the Press, Firing Line or a full house of cable news shows. His rigorously researched and painfully personal bestseller The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand why white American evangelicals came to be in the tank for Donald Trump, how it is that deeply faithful followers of Christ came to desire not holiness but power and security.

Greg Garrett

In our conversation, I asked Tim to reflect on the writing of The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory, the journey it took him on, and about his own faith. You will find Tim generous with his reflections and bracingly honest. I am grateful to Tim for this conversation and hope it will be a blessing to you.

On the day Tim and I spoke, white evangelical Christians had recently given Donald Trump the primary victory in Iowa that seemed quite likely to assure him the Republican nomination. These white evangelicals had not gone into those votes holding their noses; they had supported Trump enthusiastically because they believed he was the right man for the job — maybe even God’s man for the job.

Greg Garrett: I’m wondering if maybe we could start off with this. I mean, you’re a journalist, you’re usually focusing on subjects, but in this book, you wrote about something that is so personal to you. I wondered if you could talk a little bit about not so much why you chose to write this book, because you’ve talked about that quite a bit, but maybe what you learned about yourself and what you learned about your faith or your faith tradition by going on this journey.

Tim Alberta: At the outset I was really quite anxious about what I was going to discover on this journey and how it might adversely affect my faith. I worried that all the ugliness and the hypocrisy and the cynicism I had encountered, that might have just been the tip of the iceberg, and that once I really dove in and immersed myself in this world, I might just be overcome by that darkness.

It was a genuine fear of mine, of my wife’s. I prayed about it. So maybe at a subconscious level, I sort of played a little bit of a psychological game with myself, kind of bracing for the worst. And I think that probably was good, because I did go on to encounter some pretty soul-crushing things.

“I never felt a moment of despair about Jesus. I never felt a moment of questioning my faith.”

But what’s interesting, and I say this with total honesty: I never felt a moment of despair about Jesus. I never felt a moment of questioning my faith. I was almost operating on these two parallel tracks, one where I’m observing all these things that are just gut wrenching and so discouraging and that made me want to throw up my hands and walk away from the project. And yet on the other track, I felt this perpetual reassurance and, I suppose, truly a peace that passeth all understanding.

That was the lifeline for me that kept me going through some pretty dark days with this project.

GG: Some of your own people hurt and disappointed you. I know what that feels like, as do so many of our readers. Yet Russell Moore says if he were coming out of anesthesia and someone asked him about his faith, he would still mumble, “Southern Baptist.” How would you characterize yourself now as you think about where you see yourself fitting in the church? Your faith is strong, that’s clear, it comes across in the book, but having been on this journey, encountered such disappointment, where has it left you in terms of the organized church?

TA: I’ll start by saying I’m now a member of an independent church. I’m not a denominational guy anymore. That was not by design. But when my wife and I moved back with our boys to Michigan, we knew we could not attend the church I grew up in. There was too much baggage, even aside from the fact that at a certain point, you need to forge your own faith community, find your own people and your own church.

“It’s harder to get a foot in the door and talk to somebody about Jesus when they assign to you all the trappings of that label.”

So my church happens to be nondenominational. Now, it’s still Reformed, a church that in many ways reflects some of the evangelical tradition of my youth, but I would not self-identify as an evangelical for the simple reason, as I write in the book, I just believe the label now does more harm than good to the actual task of evangelizing. It’s harder to get a foot in the door and talk to somebody about Jesus when they assign to you all the trappings of that label.

Tim Alberta on “CBS Sunday Morning.” (Video screen cap)

And so it’s interesting, Greg, and obviously Russell talks in, I think, chapter four of my book about how for him being a Southern Baptist came to be an impediment to just being a Christian. I sort of feel the same way about the tribal affiliation of being an evangelical.

I don’t see any place in Scripture where we are called to be evangelicals. I don’t see any place where we’re called to be Presbyterians. What I see is a call to follow Jesus and to take the gospel to all the nations and to make disciples. And so just being a good old-fashioned follower of Jesus is good enough for me in the category department.

GG: Early on in Donald Trump’s presidency, my mom and I were in my kitchen in Austin cooking dinner, and she was telling me why she (at that time) still supported Trump, and she rolled out the King Cyrus justification for me. Having been raised Southern Baptist, I knew the inside baseball stuff, who Cyrus was, all that. But my argument, then and now, was about having to engage in these tortured theological explanations to support Trump as a political figure when he’s not a good guy, a moral person. When he makes Christians less Christian! Throughout your book, you talk to people who bring bad readings and tortured theology to justify positions they’ve taken over the last six or eight years. But one of the things your book does, brilliantly, is respond to them with better theology, more faithful readings of Scripture. I wanted to ask, is this theological knowledge you got from just being a pastor’s son, is it from growing up in the tradition, or is there actual preparation or study that’s gone into how you are able to respond to people about how we ought to read the Bible?

TA: The answer is all of the above. When you grow up as a pastor’s kid, and not just any pastor’s kid — my dad was, boy, I don’t even have the adjectives to describe just what a serious scholar he was and how thorough. Every day of his life, even on vacations or if we were taking trips, wherever the setting was, he was in his Scripture for at least an hour. Every single day of his life. And the conversations you’re having, the wisdom he’s imparting to me and to my brothers. … So yes, there’s a lot of just good theology by osmosis that’s passed on.

Then on top of that, I’m growing up in the church physically, literally growing up in the church. It’s my home. You don’t necessarily appreciate it at the time, but you’re marinating in the message even just reciting the creeds and singing the hymns, and it’s constantly reinforcing some of the core essential elements of the gospel. So I think that’s a huge part of it. It’s just my upbringing.

“I want to always be prepared to give an answer for the hope that I have.”

The other thing I would say is I’ve really made it my mission now that I’m a dad and now that I have a family of my own, a church community of my own, I want to always be prepared to give an answer for the hope that I have. And so that means study. That means doing programmatic things to ensure not only am I growing, but I’m also interrogating my own beliefs and my own interpretations, and I’m challenging myself to be better.

My dad’s successor said to me years ago that the Bible is a mirror we hold up to ourselves. I think that’s so true. The only way to see our flaws, the only way to see our sin nature, the only way to really examine the ways in which we remain broken and depraved is to hold that mirror up to ourselves every day. And hopefully what comes of that is sanctification. That’s been a big part of my journey as well: If there is a lot of bad theology out there, the best remedy for bad theology is good theology, but you don’t get there overnight. It’s a journey.

GG: In The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory, you describe something Pastor Brian Zahnd said to you looking out over the seeming wreckage of white Christian evangelical faith and practice: “Jesus deserves a better Christianity than this.” I’m Episcopalian; we have our own sets of sins for which we need to repent. I’d guess every group of Christians does, seeing how we’ve all sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. What do you think it might look like for Americans to find a better Christianity?

Tim Alberta: I often reflect on the original Christians and how they were removed from the fears about influence and power and prestige because they knew their identity was rooted in something so much greater. I don’t think these folks wanted to be persecuted. I don’t think they wanted to be marginalized. I don’t think they wanted to be martyred. And yet they believed that in times of crisis, in times of danger and in feeling the walls closing in around them, they believed they had a choice.

They could turn to the Cross or they could turn to the sword, and they chose to turn to the Cross. And let’s be clear, that can sound grandiose. It can sound glorious, but turning to the Cross, it is taking the road to Calvary; turning to the Cross is suffering. It can be dehumanizing, it can mean the loss of everything we have ever known in this life.

And yet it is not about this life. And that is such a strange concept for American Christians specifically.

“It becomes so difficult for us, for me, to relate to the vagrant preacher from the ghettos of Nazareth who was hung on a tree naked.”

If you think about white Protestant Americans, they are in the 100th percentile of the birth lottery in the history of the world, right? There’s nobody who’s ever had it any better, and probably nobody who ever will have it any better, right? And so it becomes so difficult for us, for me, to relate to the vagrant preacher from the ghettos of Nazareth who was hung on a tree naked. It becomes so difficult to relate to the first century church living under a brutal Roman occupation, these early followers of Jesus who are in prison singing hymns, being led to their deaths and yet praying for their executioners, right?

I mean — really mean, not just as a rhetorical flourish, but I’m asking the question — how can we possibly connect to these big brothers and big sisters in the faith? And I think the only way to begin to reconnect to that early church tradition is to make ourselves vulnerable, is to humble ourselves to the point where we begin to think about what a life without power and influence and wealth and fame and political connection and tribal dominance looks like.

And by the way, when we see it, we might be terrified by what we see because it might look altogether different from everything we’ve ever experienced. And we might say, “Boy, I’m not sure I want anything to do with that.” And yet, just maybe a little bit of real persecution, a little bit of real marginalization, a little bit of being under siege really and truly is the best thing that could ever happen to the American church, because perhaps that is what draws us back closer into relationship with the founding of the church itself, and really draws us into a more intimate relationship with Christ.

And so that’s true at an individual level. It’s true at a congregational level. But I also think it’s true at sort of an institutional level. And, again, I’m not a masochist here. Listen, I enjoy the comforts and the privileges of my life, and I don’t want to sound insincere in saying any of this. But my mother is on a missionary trip in Thailand right now, and I’m seeing the photos she’s sending, the video she’s sending every day, and corresponding with her. And I see the joy and just the gratitude and the beauty of these people who have none of what we have, and yet they do have the one thing that we all need, and that’s Christ.

GG: That’s a powerful word. Let me plant one thought here, because I came back to faith in the Black church. I’m aware the Southern Baptist tradition I grew up in and the theological orientation of the Black church are very different, but having been in this place with people who’ve been marginalized and been in that place of dispossession you’re talking about, that the white church in America has not been in, it feels like there is so much the white church could learn from the Black church, from marginalized churches in general. You were just talking about the church in Thailand and the faithfulness of believers there despite what looks to us like poverty. One of the biggest questions in my own faith life and in my working life as a theologian and as a writer is this: What are the things I missed because of my particular orientation that could help open a door to being a more faithful Christian in America at this moment?

TA: Yeah, it’s a great thought. Onstage last night at this event in New York I was talking about this wonderful conversation I had, I don’t know, maybe a month ago at a TV studio in Washington. One of the producers afterward, middle-aged Black woman, came up and had some nice things to say, and we had a good conversation. She was talking about this idea of the church being under siege, about Christians turning to Trump out of this existential dread, this panic. And she said, “Yeah, this is where I — and she described herself as culturally conservative, politically, theologically conservative — she said, yeah, this is where I break with some of my white brothers and sisters, because we know what it means to be under siege.”

This concept is not just academic or abstract for so many. And I thought that was a really important insight, and it’s stuck with me. But you’re right, Greg, about widening our vision. I’m thinking about even moving back home and joining a new church. My wife is not white, and that was one of many reasons why we were never going to just go back to my home church. She wants to be in a body of believers that looks like the body of Christ.

We live out in the Ann Arbor area, and to see the difference between our church now and my church I grew up in? It’s almost like when you walk into the U.S. Capitol and you go up into the House Gallery, and you look down at the floor, and you see the Republicans on one side, which looks like a Georgia Country Club from the 1940s, and then you look at the other side, and it looks like America.

That contrast is exactly what it feels like now comparing our current church to my home church. And it’s not to say that you can’t grow and learn and flourish in an all-white church because there are plenty of people who do. But I certainly take your point that there are those of us who could benefit from some sort of change of scenery or kick in the pants, could find necessary wisdom in a different tradition.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Politics, Faith and Mission: A BNG interview series on the 2024 election and the Church

Journalist’s book explores ‘crack-up of the American evangelical church’