The first thing that’s essential to know about this story is that there are two churches in North Carolina named Wake Forest Baptist Church. That’s important not only for clarity but also for historical context.

One of those churches announced Aug. 7 that it will close, but the other is still very much open and not closing. The two churches share a history that intersects a formerly Baptist university but have taken different paths not entirely of their own making.

This is a story about the tremendous changes in higher education in the past century, mixed with tremendous changes in church attendance patterns — with a dash of COVID thrown in for good measure.

This is a story about the tremendous changes in higher education in the past century, mixed with tremendous changes in church attendance patterns — with a dash of COVID thrown in for good measure.

Wake Forest Baptist Church of Winston-Salem, N.C., announced last Sunday that it will dissolve sometime later this year. That decision was the result of a months-long discernment process necessitated by dwindling membership, cultural changes and the imposition of a $30,000 annual rental fee from Wake Forest University. Since its inception in 1956, the church has met on the university campus and owns no property of its own and never has paid rent.

This Wake Forest Baptist Church — the second church to bear that name — has made a name for itself as a beacon of progressive Protestant Christianity, being early to advocate for racial integration, early in Baptist life to ordain women, and early to perform same-sex marriages.

Those progressive stances have not always been met with cheer by the university, which was founded by North Carolina Baptists.

From the beginning

The history of Wake Forest Baptist Church — the first one — dates to 1834, when North Carolina Baptists established Wake Forest Institute. The school’s purpose was to provide young men with agricultural training along with sound religious instruction. The school later was renamed Wake Forest College.

A physician in the town of Wake Forest sold the Baptists 610 acres of land for the new school, and by 1835 a Baptist church had been founded on the campus — intentionally planted there in a symbiotic relationship with the school.

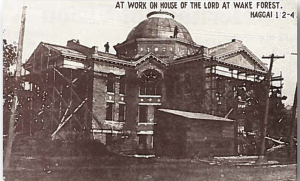

Samuel Wait, president of Wake Forest Institute, served as the first pastor of the church. The congregation was made up primarily of students, faculty and a few enslaved servants. For nearly 80 years, the church met in campus buildings, until in 1913 ground was broken for a dedicated church house on campus property. The first service was held there in February 1915.

Samuel Wait, president of Wake Forest Institute, served as the first pastor of the church. The congregation was made up primarily of students, faculty and a few enslaved servants. For nearly 80 years, the church met in campus buildings, until in 1913 ground was broken for a dedicated church house on campus property. The first service was held there in February 1915.

In time, the bustling church drew members from the college, from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary (a Southern Baptist Convention school founded in 1951) and from the growing town of Wake Forest — a town largely created by the presence of the college.

But all that changed in 1956 when Wake Forest College packed up and moved 100 miles west to Winston-Salem, N.C., where it became Wake Forest University. The fledgling Southeastern Seminary acquired the college’s original campus in Wake Forest, where it remains to this day.

A second Wake Forest Baptist Church

Upon arrival in Winston-Salem, the faculty, staff and students who had been members of Wake Forest Baptist Church created a new on-campus church home — also called Wake Forest Baptist Church. Like the original campus congregation, this was founded as an autonomous entity — Baptists love the word “autonomous” — but from its inception met in campus buildings.

The Winston-Salem iteration of Wake Forest Baptist Church never has owned anything. For many years, the church met in the university’s Wait Chapel, a 2,000-seat auditorium. But the church’s membership peaked at somewhere between 400 and 900 people — depending on who’s telling the story — and that was in its early years.

The 19th century and early 20th century expectations that faculty, staff and students at a Baptist college would be regular worshipers at a Baptist church began to break apart.

The 19th century and early 20th century expectations that faculty, staff and students at a Baptist college would be regular worshipers at a Baptist church began to break apart. By the 1960s, students stopped going to church or began attending other off-campus churches. And in 1986, North Carolina Baptists broke formal ties to the university, freeing the school to become both more secular and more religiously diverse.

All these social and cultural changes led to a steady decline in attendance at the on-campus church. Fewer university faculty were Baptists, and fewer of those who were Baptists chose to return to campus on Sundays. Fewer students attended church at all, and fewer of those who did chose to stay on campus for church. What once had been an asset in location now was a liability.

Nevertheless, the Winston-Salem Wake Forest Baptist Church carried on and found its voice as an advocate for progressive theology and social justice.

Nevertheless, the Winston-Salem Wake Forest Baptist Church carried on and found its voice as an advocate for progressive theology and social justice.

In 1962, the church declared its membership open to all races. The university, which had been more reluctant to embrace this controversial social change, soon followed suit and accepted a student from Ghana as the first full-time undergraduate at the Baptist school. Wake Forest thus became the first major private university in the South to desegregate — a move sparked by the on-campus church.

The same was not the case, however, when the church performed its first “covenant service” for a same-sex couple in 2000. In the months leading up to that event, church and university officials went back and forth — ultimately involving university trustees — about whether the autonomous church could bless a same-sex union on university property.

Because of that church action, relations between the Wake Forest School of Divinity and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship became strained.

The on-campus church also was a founding congregation in the Alliance of Baptists, another breakaway group from the SBC predating the formation of CBF. The Alliance has a long history of full inclusion of LGBTQ persons, while CBF’s position on inclusion has been more tortured and complicated.

Later, Wake Forest Baptist Church drew national headlines for calling lesbians as co-pastors and for ordaining a transgender woman.

“Our motto at Wake Forest Baptist Church is ‘All are welcome, no exceptions.’”

A statement on the church’s website explains: “Our motto at Wake Forest Baptist Church is ‘All are welcome, no exceptions,’ an idea which is undergirded by the incarnation of Jesus, God-among-us, in the form of a vulnerable, poor and marginalized person to show us how God loves us all.”

Factors leading to the closing

As controversial as this recent history may be, those actions are not the primary reasons for the church’s dwindling membership — down to 25 to 30 people today — and the decision to close, according to multiple people with direct knowledge of the decision. In a sense, the die was cast decades ago by the same social and cultural trends that challenge every church in America today.

Rayce Lamb

“The religious landscape in America is changing rapidly, and more rapidly in higher education,” said Rayce Lamb, interim pastor at the church and a staff member at the university’s divinity school. “Churches are having to imagine new ways of doing ministry, and then you throw COVID on top of it. They either need to change or die well.”

Amid the COVID pandemic — which further cut into the mainly retirement-age congregation’s attendance — the church began an intentional discernment process about its future. That process was started by Lia Scholl, who was pastor there from 2014 through late 2021. She now serves a Quaker congregation.

When Scholl arrived, she preached to about 50 people each Sunday in a room designed to hold 2,000. During her tenure, she led the congregation to relocate to a smaller chapel in the same university complex.

When Divinity School Dean Jonathan Walton told her the university would begin charging the church rent — and the timing of this is a disputed point among on-campus figures — she negotiated with him and the university on the church’s behalf. By some accounts, the university had notified the church of the rent earlier, under a previous administration, but never had collected any rent in the subsequent years.

Wake Forest Baptist Church currently meets in Davis Chapel on the university campus.

Regardless of who told who what and when regarding the rent, the church now was going to incur the reality of a significant new expense. Scholl knew the church could not afford to pay a pastor and the rent both. She resigned, and the church took a hard look at its future.

Lamb, who already was a member of the church, stepped in to serve as interim pastor and help guide the rest of the discernment.

The decision to dissolve the church is not the result of any one factor, he emphasized. “From a pastoral perspective, this was a hard decision for my folks. … They still see a lot of hope for how to be a progressive force. They are a hopeful people. We believe God is calling us to something new.”

“They are a hopeful people. We believe God is calling us to something new.”

No date has been set for when the church will hold its last service, but that’s likely to be several months from now, he indicated. “We have some ministry commitments we intend to honor throughout the fall.”

Meanwhile, the next step is to determine how to use the church’s remaining assets to perpetuate its mission, he said. Even though the church owns no property, it does have cash assets.

The university response

Walton, who serves as dean of the divinity school, responded to BNG on behalf of the university.

Jonathan Walton

“It pains us to think that so many small, independent congregations across this country are having to make such difficult choices,” he said. “We know the pandemic hastened the trends of congregational disaffiliation that have been taking place for decades. Fortunately, I also know that Wake Forest Baptist Church’s commitment to justice, inclusion and making our nation a better place will continue through the many people the church has inspired.”

Wake Forest students who want to attend religious services have many options to do so, he added. “The university offers a wide array of worship opportunities for the student body. There are about three dozen campus ministries on the Wake Forest campus, ranging from weekly Catholic mass, Hillel, and Baptist Student Union. The University will also continue to provide worship opportunities for the campus community and beyond through LoveFeast, the annual Homecoming Worship Service, and sacred music concerts.”

And as to the cultural and social trends facing Wake Forest Baptist Church, “this is the daily work of Wake Forest University School of Divinity,” he said. “The divinity school seeks to foster agents of justice and architects of hope and equity in the local church and other professions such as education and health care. The work of the ministry will always be rooted in but must reach far beyond congregational ministry.”

A lasting legacy

Lamb, the interim pastor, sees the future of the church in its legacy — from the bold stances that continue to echo through Baptist life and beyond to the influence on thousands of students who were shaped in their formative years by the church.

One such person is Erica Saunders, a transgender woman ordained to ministry at Wake Forest Baptist in 2019. She now serves as pastor of Peace Community Church in Oberlin, Ohio.

Erica Saunders

“The church’s closure raises some questions,” she said. “What does it mean for your ministry when your ordaining church dissolves? Could closing the doors become its own act of ministry?

“I’m deeply grateful for the witness of Wake Forest Baptist Church. They welcomed me when I doubted I belonged in the church. They nurtured my gifts for ministry as I discerned a calling. And they showed me what living faithfully means: loving everybody, without exceptions.

“By accepting its limitations and entering the closure process with intentionality, the congregation could provide an example to other congregations in similar circumstances.”

Related articles:

North Carolina Baptist church ordaining trans woman to gospel ministry

Naming and un-naming: Slavery, schools and the present moment | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Unexpectedly, a church and a seminary at odds theologically find common ground in mutual respect

Remembering the struggle to integrate even ‘progressive’ Baptist churches in the 1960s | Analysis by Alan Bean