The COVID-19 pandemic isn’t Richard Wilson’s first go-around with a deadly virus outbreak.

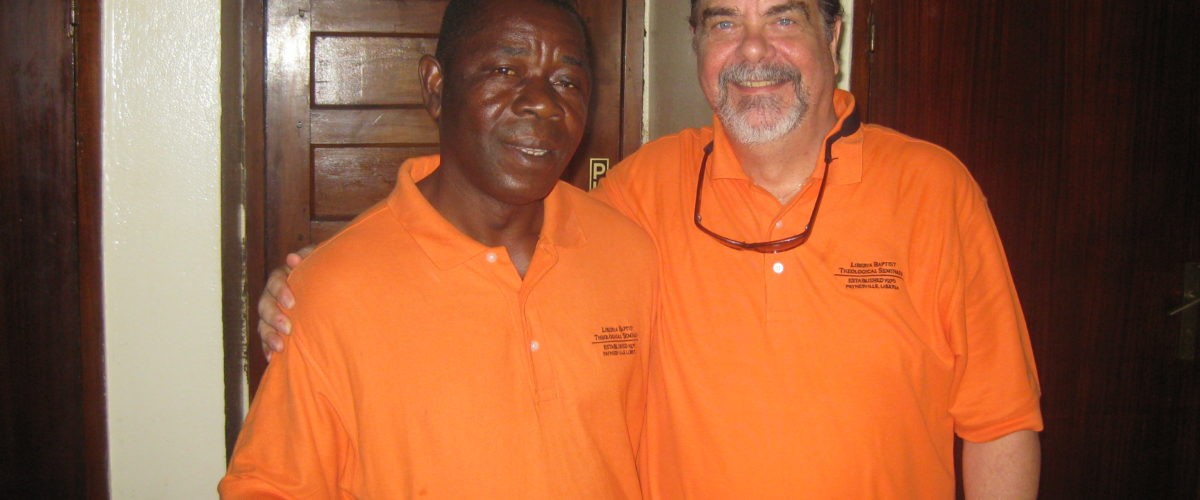

He’s the Columbus Roberts Professor of Christian Theology and chairman of the religion department at Mercer University. He also served as president of the Liberian Baptist Theological Seminary from 2014 to 2016 — a tenure nearly coinciding with the West African nation’s Ebola outbreak.

“It came fast and furious and killed a lot of people,” he said.

Ebola’s spread sparked global headlines as it killed 11,310 in Liberia and in neighboring Sierra Leone and Guinea over two and a half years, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

So far, Liberia’s 4.8-million population has suffered about 1,300 COVID-19 cases and just over 80 fatalities, the World Health Organization reports. But Wilson knows from being in the U.S. that those numbers can change quickly. “I keep telling my Liberian friends that COVID is more contagious than Ebola and that they need to be careful.”

The two outbreaks have a lot in common, including school closures, drastically altered social lives and negative economic impacts. But one of the major differences between Ebola in Liberia and the coronavirus in the U.S. is in leadership. It was, he said, much better in West Africa.

“I miss the strong leadership from the head of the government that trickled down even into the rural communities. I wish we had that kind of leadership, but we don’t. Liberia was the first of the three countries to be declared Ebola-free, and it was because of the rapid response of the government, which was very bold.”

Wilson spoke with Baptist News Global about the role of government, faith and culture in the midst of an epidemic or pandemic.

What’s it like to experience two deadly virus outbreaks?

That’s a really good question. Since we came under the coronavirus pandemic, my level of correspondence with Liberians has gone up significantly. The Liberians who were involved in our Ebola relief efforts are very empathetic about what’s going on in the United States. Daily I get encouraging messages from some of my former students and colleagues in Liberia.

When and how did you first learn Ebola was coming to Liberia?

It was in early 2014. I had just arrived in Liberia. In early February, Olu Menjay and I made the long journey to the place where Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia converge. Olu is one of my former students at Mercer who was principal and chief administrative officer at The Ricks Institute in Liberia. As we listened to the radio on that long drive, we heard the first report of Ebola in Guinea. We were concerned. People in Africa knew about Ebola because of the devastation it carries. When we arrived at our destination, we were very cautious because we were within three miles of Guinea and a couple miles from Sierra Leone. Ebola was part of our conversation from then on.

On our way back to Monrovia we kept hearing about Ebola on the radio, but the driver said it wouldn’t matter until it came to Monrovia — that’s when we will take it seriously. He turned out to be quite the prognosticator. Because when it arrived in Monrovia, it exploded.

How did the churches in Liberia react when that happened?

The saddest thing was that the Pentecostal influence made a lot of people emboldened to ignore precautions. They would make announcements to just pray and the Holy Spirit will bring us healing. But the ministry of health was making very explicit announcements about how dangerous Ebola was.

One of the things the government said was no handshaking and no hugging and do not touch a sick person. And all of those things flew in the face of Liberian culture. Liberia is a hugging and handshaking culture. When someone gets sick in Liberia, all the relatives come and stay in the house until that person gets better. The ministry of health was saying don’t do it.

But there were those who thought the power of prayer would deliver them, and they would hold healing services. Someone who was sick would be brought into the middle of the congregation, and people would lay hands on them. Some of the highest death rates were in churches during the pandemic.

“The religious component was a detriment in many places, much as some of it has been a detriment in our response to COVID here in the United States.”

The religious component was a detriment in many places, much as some of it has been a detriment in our response to COVID here in the United States. These crazy people who make false claims about divine protection don’t understand the words of Jesus in the desert: “Do not tempt the Lord your God.” I sense that Ebola and COVID are very similar in that regard.

Did you ever see faith as a positive force during the Ebola breakout?

I saw God at work in the empathy and compassion of the common people in Liberia. That would be manifested in places like the local market, where a merchant selling fruits and vegetables under an umbrella would have a handwashing station with a bleach-and-water mixture in a bucket with a spigot, and the merchant would make that station available to anyone. Ebola is transmitted through bodily fluids, and so people knew about the need for sanitation.

At the seminary, when we opened in 2015, we had sanitation stations in front of every classroom and in front of the chapel. And people generally avoided physical contact. The handshakes and the hugs pretty much disappeared. I was impressed at the eagerness of Liberians to teach each other what had to be done.

And that was happening in the churches, too. In 2015, I was in the pulpit of a different church each Sunday. From the largest urban church to the smallest rural church, everyone had those sanitation systems.

Were the seminary and other schools able to engage in distance learning during the closures?

After the government banned educational institutions from gathering in late 2014, there was no opportunity for distance learning. They didn’t have the broadband, for one thing.

It sounds like a lot of people complied with restrictions.

Yes. The cab drivers were an example of that. A third of Liberia lives in Monrovia, and most people do not drive, so the city is full of cabs. And during that time the cab drivers agreed to reduce the occupancy of their vehicles so passengers wouldn’t contact each other. It really is quite remarkable how almost everyone pulled together.

President (Ellen) Johnson closed everything and put all government workers on even-odd work days, reducing the population of office buildings by 50%. She couldn’t demand that of private businesses, but she modeled the safe practice and many businesses followed it.

“The United States is the most individualistic place on the planet, and at times we are obnoxious about our personal freedoms and ignore our corporate responsibilities.”

What can Americans learn from the Liberian experience with Ebola?

I think we in the United States have a lot to learn from people of West Africa who understand the importance and solidarity of community. The United States is the most individualistic place on the planet, and at times we are obnoxious about our personal freedoms and ignore our corporate responsibilities. I think that is a lesson we in the United States need to learn.

What do you hear about the Liberian response to COVID-19?

The pastor of my home church in Liberia, the James R. Davis Memorial Baptist Church, in Monrovia, called me when Liberia first got COVID, and he expressed a need to launch a feeding program. He has adapted the feeding program we used during Ebola for COVID. Most of it has been Liberians helping Liberians. The church has distributed 2.5 tons of rice to Liberians who are over the age of 65. This enables people to stay home instead of going into markets where they can be exposed to COVID. I find it encouraging. My friend learned something from the Ebola experience, and he applied it in the middle of the COVID pandemic.