Two days after Raymond Bailey’s death on the First Sunday of Advent, I talked about him at my church staff meeting. I told the staff how Raymond taught me to preach, showed me how to be a minister and pushed me to be my best. I told them Raymond saw something in me no other teacher saw and helped me see things I would not otherwise have seen. I told them I loved him. When I finished, I offered an opportunity for identification, as Raymond would have insisted.

I asked, “Who have been your mentors? Who has invested in you? Who has helped you explore your calling?”

No one said anything for a long time.

Finally, Bruce, our minister of music, said, “I don’t think any of us have anyone like that.”

I thought, “Of course not, almost no one does.”

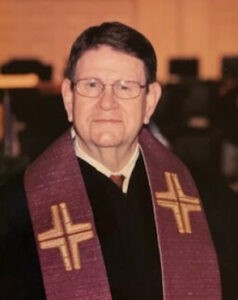

Raymond Bailey

I was at Wednesday night supper at Baptist Tabernacle in Louisville, Ky., in 1985. Raymond’s wife, Pat, my wife, Carol, and I were on the church staff. Raymond had been on sabbatical for the last year, so I had the misfortune of having to take another professor for Introduction to Preaching.

Everyone said the same thing about the preaching professors at Southern Seminary: “If you want to make an easy A, here’s who you take. If you want to write religious essays, take this professor. If you really want to preach, take Bailey.”

Even my inferior introduction was enough to let me know that I wanted to study preaching. Raymond, whom I had just met, asked about my plans. I told him I wanted to pursue a degree in preaching. I already had lined up a lesser professor to be my supervisor.

Raymond asked: “Why do you want to preach? What do you want to learn? What do you want to do?”

We talked for a long time about rhetoric, communication and the future of the church.

At the end he said, “Go tell the professor you’re planning to work with what you have told me, and then ask him who should be your supervisor.”

That’s how Raymond became my supervisor.

During his 16 years at Southern Seminary, he was considered demanding because he wanted us to understand that what we were learning was important.

“During his 16 years at Southern Seminary, he was considered demanding, because he wanted us to understand that what we were learning was important.”

He said of one student’s sermon, “You seem to be answering a lot of questions that no one is asking.”

Another student presented a paper that didn’t suggest he had done a lot of work. Raymond asked, “When I finished your book review, the question that immediately leapt to mind was, ‘Did you ever get a chance to read the book?’”

I spent eight years as a preaching professor asking, “What would Raymond do?” I usually did it — which got me into trouble a few times.

He taught us how to be ministers. After Carol went through a miscarriage, Raymond and Pat could have called, sent a card or made a point to see us the next time we were in Louisville, but they didn’t. They drove to Paoli, Ind., and let us talk about how terrible we felt. They hugged us, prayed for us and then drove back to Louisville — as though that’s the kind of thing professors do.

He urged us to be real ministers: “Preaching emerges from the work of the pastor. The pastor can’t hide in her or his study. You have to spend time with people and get to know their joys and sorrows.”

He insisted with T.S. Eliot, “The greatest temptation is to do the right thing for the wrong reason.”

Whenever I am tempted to re-preach an old sermon, Raymond’s voice pops into my head saying, “Preaching is a particular message for a particular people at a particular time.”

I wish that particular line would stop popping into my particular head.

Raymond always was an advocate, so in 1994, I asked him to recommend me for a pastorate in which I was interested.

He said: “I’m sorry. I can’t do that.”

I was stunned: “Dr. Bailey, if you don’t mind me asking, is there a reason?”

“I already applied to Seventh and James, so I think it would confuse the committee.”

Seventh and James Baptist Church in Waco made the right choice. Raymond had an amazing 15 years of ministry there and is much beloved.

“Raymond believed in remnant theology, that even when the church loses its way, God is still going to find ways to do God’s thing.”

He taught us to care about social justice, fight racism and embrace diversity. He wanted us to be hopeful about the church. Raymond believed in remnant theology, that even when the church loses its way, God is still going to find ways to do God’s thing.

On a Facebook post with the Bailey family Thanksgiving pictures, Raymond’s son-in-law Alan writes: “Since 1989 the Bailey Clan of Raymond and Patricia has challenged me to be a better human being. I am thankful.”

Raymond had about 2,000 high school, university and seminary students, and who knows how many church members, who could write those words: “Raymond challenged us to be better human beings. We are thankful.”

A couple of months ago, Raymond sent an article he had written that concludes: “After 80 years plus of life and over 50 in ministry, I am still pressing on my calling to reflect the image of God. The journey is incomplete in human time and space. The human heart aspires to that which lies only in the province of the Crucified Christ.”

At his funeral, I said: “Raymond has found that to which he aspired and led others to aspire, the province of the Crucified Christ, that which he has preached and taught others to preach. The God of Jesus Christ, the God whom Raymond loved, has welcomed Raymond home.”

Brett Younger

Brett Younger serves as senior minister at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Related article: