By Bob Allen

Jesus’ command to “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” sounds straightforward, but a new book by a Baptist scholar says the line between religion and politics isn’t always clear.

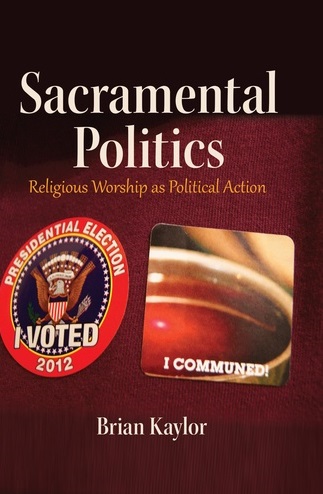

In Sacramental Politics: Religious Worship as Political Action, author Brian Kaylor explores both how religious worship is used — and misused — in politics and the inherent political nature of elements of religious worship. Peter Lang, an international academic publishing house based in Switzerland, published the book, released Dec. 15 and available through Amazon.com.

Kaylor, a former university professor, says conservative evangelicals were understandably concerned in 2013 when the IRS held up tax-exempt applications for certain groups, asking questions specifically related to prayer meetings. The question was not about the content of prayers, however, he says, but the purpose.

Kaylor, a former university professor, says conservative evangelicals were understandably concerned in 2013 when the IRS held up tax-exempt applications for certain groups, asking questions specifically related to prayer meetings. The question was not about the content of prayers, however, he says, but the purpose.

Kaylor, who works as communications leader for Churchnet, formerly the Baptist General Convention of Missouri, and contributing editor for EthicsDaily.com, website of the Baptist Center for Ethics, contends that prayer sometimes is an act of worship and politics at the same time.

To illustrate how a single act can be both secular and sacred, he draws on the Catholic doctrine of “transubstantiation,” the belief that in the Eucharist elements that continue to appear as bread and wine are miraculously transformed into the “Real Presence” of Christ.

Kaylor says public prayers delivered at political conventions, for example, serve both to “communicate with a deity” and “refocus human attention on human concerns.” By invoking a blessing at such gatherings, he says, both parties infer “divine partisan favor” on their behalf.

“These public prayers therefore occupy a unique position in the religious-political spectrum,” he said. “They are not merely a mixing of religion and politics, but rather a unique speech act that exists as both a religious act and a political act.”

Arguments about the separation of church and state aside, Kaylor contends, the fact that something is said in a religious setting doesn’t mean it isn’t political speech. “Pulpit Freedom Sunday,” an annual event by conservatives protesting an IRS ban on political endorsement by churches that are tax-exempt, for example, “transubstantiates” partisan politics into religious worship “so that the two elements became a new act.”

Kaylor doesn’t argue that religious worship should not be transubstantiated with politics, only that when the two are mixed “they become a new type of action with important religious and political implications.”

Kaylor said if concern for the poor is central to a person’s faith, for example, talking about Bible teachings about helping the poor will naturally influence that individual’s political views. The danger, he said, is when religious worship is married with politics in ways that undermine the faith’s teachings or surrender allegiance that belongs rightfully to God.

“Clergy and churchgoers should carefully think about religion and politics,” Kaylor said. “In particular, attention must be given to dangers of mixing religious worship with partisan politics and to the political messages already embedded in religious songs, scriptures and liturgies.”

“Clergy and churchgoers should carefully think about religion and politics,” Kaylor said. “In particular, attention must be given to dangers of mixing religious worship with partisan politics and to the political messages already embedded in religious songs, scriptures and liturgies.”

While politicians can and do exploit religion to seek votes, Kaylor says even sincere religious devotion by candidates can send a political message.

Texas Gov. Rick Perry hadn’t officially announced he was running for president when he spoke in 2011 at a prayer rally called, “The Response: A Call to Prayer for a Nation in Crisis,” Kaylor said, but publicity about the event made him an instant front-runner for the Religious Right.

President George W. Bush received the highest approval ratings for any modern president after the 9/11 National Day of Prayer and Remembrance, remembered less as an act of mourning than a tool to create national unity in a war on terrorism.

President Obama’s selection of Saddleback Church Pastor Rick Warren to pray at his first inauguration, meanwhile, backfired in controversy among gay-rights activists due to Warren’s outspoken support of California’s Proposition 8 opposed to same-sex marriage.

Kaylor’s first two books also explored issues of religion, politics and communication: For God’s Sake, Shut Up! (Smyth & Helwys, 2007) and Presidential Campaign Rhetoric in an Age of Confessional Politics (Lexington Books, 2011). The second book, examining religious rhetoric in presidential campaigns, won multiple awards and was featured on CNN.com and numerous news outlets.