Religious freedom conditions have worsened in Burma this year as government influence continues to wane and armed ethnic groups amass power and territory in the nation’s ongoing civil war, according to a report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom.

The threat to religious belief emanates from the military government’s targeting of ethnic and religious minorities, the junta’s battles with resistance groups and often from friction between those ethno-religious organizations. The United Nations estimated in September that more than 5,300 civilians have died and more than 3.3 million have been displaced in the conflict since it began in 2021.

By March 2024, the Buddhist-controlled military and its State Administrative Council reportedly lacked firm control of about 86% of the nation’s territory and 67% of its population, USCIRF reported. The erosion of power began in earnest last fall when armed ethnic and other resistance groups began consolidating territory in several regions and states.

The threat to religious belief emanates from the military government’s targeting of ethnic and religious minorities.

But those gains have not deterred government forces from attacking the leaders, sacred sites and communities of Baptist and other religious minorities as it has since the outset of hostilities, according to the report. “At the same time, the military junta’s aerial superiority enabled it to target resistance groups, including religious communities that support these groups, even as the resistance has made advances on the ground.”

Those movements include the National Unity Government, a popular pro-democracy organization whose stated intention is to reshape Burma — also known as Myanmar — into a peaceful, multi-ethnic nation. But while the group has attempted to include broader religious participation, faith minorities have voiced concern it is controlled by the nation’s Bamar Buddhist majority, USCIRF noted.

The predominantly Baptist Chin ethnic group created a “Chinland” constitution in 2023, pledging a secular government in opposition to the Buddhist-nationalist rule of the junta. But stability has been lacking in the regions controlled by armed ethnic actors, USCIRF added.

“In May, tensions erupted between groups associated with the Chinland Council and other Chin State ethnic organizations such as the Zomi Revolutionary Army. Potential conflict between various ethnic organizations within Chin State could prevent the return of Chin and Zomi peoples who fled, in part, from religious persecution perpetrated by the Burmese military.”

(123rf.com)

Events in Kachin state, the mostly Baptist region where military operations continue, have been similarly turbulent, USCIRF said. “The instability in Kachin State has heightened vulnerabilities for Christian minority communities and members of the Buddhist majority in the region whose communities, houses of worship and religious leaders the Burmese military may target for their support of the resistance.”

Tensions also have intensified in Rakhine state, where an armed Buddhist ethnic minority has staged incursions this year into areas populated mostly by Muslim Rohingya, the report states. Leaders of the Arakan Army have used ethnic slurs to denounce the Rohingya and have claimed they intend to establish an Islamic safe zone with the help of foreign powers.

“As the AA advanced in April and May, it is unclear whether the Burmese military or the AA were responsible for the destruction of Rohingya villages and towns. For example, unverified reports from the community indicate the AA was responsible for burning the town of Buthidaung.”

But 2024 also has seen the continuation of the junta’s campaign of religious oppression in areas it controls, especially by targeting leaders in order to intimidate ethno-religious minorities, USCIRF explained.

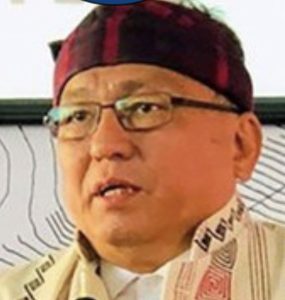

Hkalam Samson

Among them was Hkalam Samson, a Kachin Baptist Convention leader arrested and released multiple times beginning in April. At one point, he was sentenced to six years in prison on “manufactured” charges of unlawful association, terrorism and inciting opposition to the government, USCIRF reported.

Members of his community described the harassment as efforts to intimidate the KBC and the Kachin Independence Army: “On March 18, 2024, gunmen shot a Kachin Baptist pastor in Mogaung Township. On April 12, two masked individuals shot a Catholic priest during Mass at St. Patrick’s Church in Mohnyin village in Kachin State.”

Government actions this year have included constructing Buddhist pagodas in Christian-majority areas where it establishes outposts, and attacking Protestant, Catholic and Muslim facilities. More than 220 churches were destroyed in Burma from 2021 to 2023, including as many as 100 Catholic parishes in one state alone.

“Attacks on houses of worship continued in 2024,” the report says. “For example, in January, the military burned down a Catholic church in Ye-U Township, Sagaing Region. Military airstrikes on Feb. 5 struck a village church and damaged other buildings, including a school in Demoso Township, Kayah State. On May 11 and 12, military airstrikes destroyed homes and both a Catholic and a Baptist church in Tonzang Township in Chin State.”

USCIRF criticized the international community for failing to hold Burma accountable for its actions and called on the U.S. to cooperate with Burmese opposition groups and urged the Department of State to designate the nation as a Country of Particular Concern. Regional governments such as India, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Thailand should be engaged to seek an end to conflict in Burma, the report adds.

Related articles:

Two years after Myanmar coup, human suffering goes unnoticed | Analysis by Erich Bridges

Karen refugees demonstrate remarkable resilience, researcher says