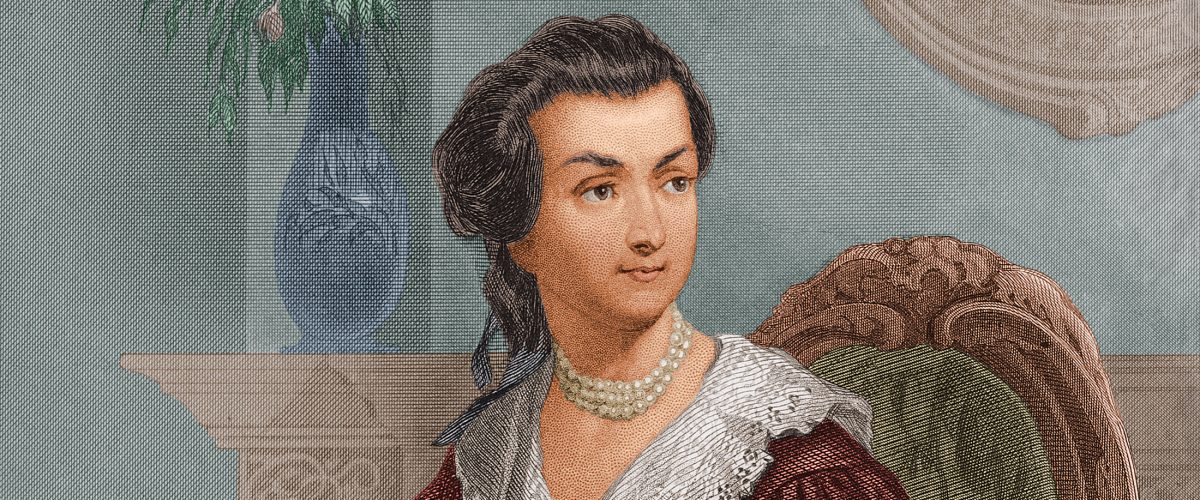

In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, “Remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember all men would be tyrants if they could.”

On this Election Day, we realize how right Abigail Adams was — and continues to be. We’ve seen in recent days women’s rights rolled back, ugly names for women tossed around as legitimate political discourse, and even calls issued to repeal the 19th Amendment that granted some women suffrage.

Susan Shaw

Unfortunately, one of the key texts many misogynists (mis)use to justify their rhetorical, political, physical, and sexual violence against women is the Bible.

This fall, I’m teaching an undergraduate course on feminism and the Bible. We talk about the importance, in the words of feminist biblical critic Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, of re-membering women, reclaiming those dangerous memories of women who resisted, who claimed their right to selfhood, and who challenged patriarchal norms. For one activity, I ask students to write a poem or short prose piece retelling the story of a biblical woman.

This year, their insights were so spot on, not just for the biblical text itself, but for our current moment, that I want to share a few of them.

I wish conservative Christian men could learn to read the Bible with the empathy, reflection and compassion my students, including some who have never read the Bible before, bring to the text. If that were the case, perhaps we would not have women dying from lack of access to reproductive care or demands that wives must vote as their husbands tell them or the continued mishandling of clergy sexual abuse.

These students told me I could share their work. I’m glad. Their words can help us re-member the ladies and reaffirm their stories’ call to justice.

Eve

O. Cooper

I am the first woman

I had no mother to teach me

Only rules of how to be

One slip up, I fell for the lies

No mercy

Paradise dies

It’s all my fault, he said

It’s all my fault, pain, suffering, death.

Job’s Wife

Addison Swartzendruber

My dearest husband, Job. No one I have ever met has faithfulness as he does. They call him blameless and upright, a man who fears God and turns away from evil. I believe it has contributed to our many fortunes and blessings. The sheep and oxen, the servants and a beautiful plot of land. Our seven sons and three daughters, my pride and joys, my family. I couldn’t be more thankful for my family.

God brings these blessings, and Job thanks God, and worships God.

But just like that, one day, God took them all away.

He tested Job. Took everything he loved. But not me. I was left to watch. And Job still worshipped, like a madman.

I could not care less about the animals and the land and the nice home. I could not care less about having fewer servants (but bless their families and their hearts). Yet, just as God brought my 10 blessings into my life, he took them away. He took their lives away. And Job could have stopped him.

I found him on the floor, rubbing the sores on his skin with shards of a pot like some damned idiot. An idiot without a family, nothing but his wife to watch and melt with grief, watch as her husband takes trial after trial, a man who never once cursed God’s name. Seven sons. Three daughters. Gone within a day, the precious children, and Job still knelt, and Job still worshipped.

Tell me I was more than a fly on the wall observing these tests of faith. Tell me I have a right to feel for what was done with my children, what was done to my husband. I cleaned those scattered pot shards. I thought, tell me it has been enough! And when it finally was, when the land was restored, and when we bore new children, it was as if our world had been ripped apart and replaced.

My husband was healed the moment our world was brought anew. I saw the light in his eyes. The grass was green, and he had new children. My husband, Job, blameless and upright, a man who fears God and turns away from evil. He was quick to forgive, to push away those memories. I don’t know if I could ever do the same.

Caught in Shadows

Anonymous

They dragged me from the shadows,

a trembling figure at dawn,

my heart pounding, a drum of fear,

the weight of their eyes like stones.

I stood there, exposed,

naked not just in body,

but in spirit,

my sin laid bare before the crowd.

Where was he, the one they claimed?

Hidden, a coward among the accusers,

his silence louder than their taunts,

his absence a betrayal.

“Teacher, what say you?”

Their venomous whispers stung,

but then I felt a different presence,

a heartbeat, steady and kind.

In the dust, I found hope,

as he lifted my chin,

gaze unwavering,

no stone in his hand.

“Neither do I condemn you,” he spoke,

and in that moment, I was reborn,

not just a sinner, but a woman,

my story unfurling into the light.

Ruth

Ashley Silver

I will go with her,

vulnerable alone,

stronger together.

Leah

Amber Johnson

She’s the pretty one,

The cherished one;

I toil in childbirth not once,

Not twice,

Three times.

Love me I cry

Cherish me I cry,

But no one hears.

Hagar’s Desert Cry

Luis Nunez-Martinez

“I walk with sand beneath my feet,

the sun above a merciless weight.

A mother’s hands that once held hope,

now reach for a stream that isn’t there.

Abandoned, I call to you, unseen,

God of the promise given to another.

Is there mercy for me,

a servant cast to the barren winds?

A voice breaks the heat,

speaks to me of rivers, of futures,

of my son whose laughter will echo

in a land that was never mine.

I am heard —

in the emptiness, I am found.

And though I was a stranger,

the desert now holds a promise for me too.”

Susan M. Shaw is professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She also is an ordained Baptist minister and holds master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Her most recent book is Intersectional Theology: An Introductory Guide, co-authored with Grace Ji-Sun Kim.