One of the best friendships I made when I moved to North Carolina was with Bob Seymour, founding pastor of Olin T. Binkley Memorial Baptist Church in Chapel Hill. We shared the same birthday and often celebrated together at one of the long desegregated local eating establishments where he would tell stories.

He was as harmless as he was wise — a faithful minister and vigilant leader in the Civil Rights struggle in North Carolina. Yet as he told me, he learned the hard way.

Curtis Freeman

As a student at Yale Divinity School, Seymour was deeply influenced by the dean and fellow Southerner, Liston Pope, author of Millhands and Preachers, a classic case study of a 1929 strike at a cotton mill in the small industrial town of Gastonia, N.C. Pope’s analysis shed light on the intersection of religion, power, economics and class. It showed how the tensions between management and workers ran parallel to the struggle between Blacks and whites in the South.

A native son of Greenwood, S.C., Seymour came to understand the structural and institutional embodiment of racism in the South through Pope’s lucid social analysis. It was Pope, who in his book The Kingdom Beyond Caste, coined the phrase, “The church is the most segregated major institution in American society.”

Pope thought the church could be a force of good in society, but he noted it “has lagged behind the Supreme Court as the conscience of the nation on questions of race, and it has fallen far behind trade unions, factories, schools, department stores, athletic gatherings and most other areas of human association as far as the achievement of integration in its own life is concerned.”

Bob Seymour

After graduating from Yale in 1948, Seymour began serving as a pastor in North Carolina. He soon began advocating for the North Carolina Baptist Convention to desegregate its seven affiliated colleges. Each year he would attend the state convention meeting, and when the school administrators came to give their annual reports, Seymour would make a speech about why they needed to desegregate the schools. He received little support for his efforts.

When Seymour became pastor of Mars Hill Baptist Church in Western North Carolina, he was invited to serve on the board of trustees for Mars Hill Baptist College. At some point he became aware of the story about how during the construction of the school in the late 1850s, finances ran out and the contractor couldn’t be paid. Jesse Woodson Anderson, a trustee of the school at the time, offered his slave, Joe Anderson, as collateral for the debt until the necessary funds could be secured. Within the week, Joe Anderson was released from jail, and the debt was paid.

Seymour wondered, “What if we could find a descendent of Joe Anderson and they could apply for admission? How could the trustees reject the application?”

Oralene Simmons

With some effort and a little assistance from the Quakers, they identified Oralene Simmons, who was the great-great-granddaughter of Joe Anderson. She applied for admission in the fall of 1961. After her family story was revealed, as Seymour rightly predicted, the school admitted her, and she became the first African American to attend a North Carolina Baptist college.

When Bob Seymour first told me that story, I asked him where he came up with the idea. He said, “Jesus!” When I pressed him, he replied, quoting the Scripture, “Be wise as serpents and harmless as doves” (Matthew 10:16). Truth be told, it was Jesus, but it was the voice of his teacher Liston Pope.

All those convention speeches may have eased his conscience, but they only angered his opponents and did nothing to effect any change in policy or practice. Yet the wise and harmless act of persuading Oralene Simmons to apply for admission made a real difference. It was a lesson he carried with him over the course of his ministry.

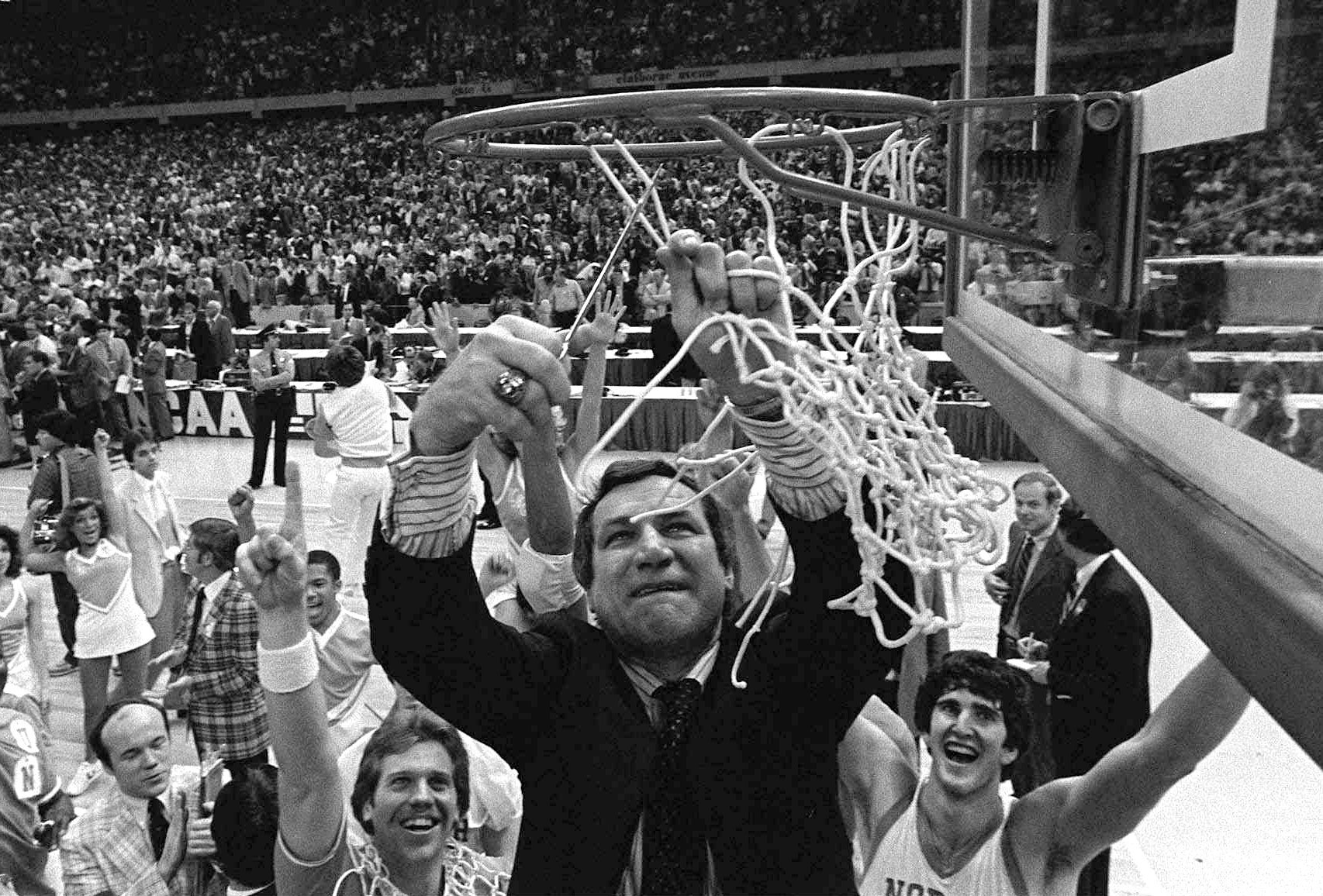

North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith cuts the net as happy players and fans cheer after the Tar Heels defeated Georgetown for the NCAA Championship March 29, 1982, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Pete Leabo)

When Dean Smith came to Chapel Hill as the head coach of the men’s basketball program for the University of North Carolina in 1961, he and his family joined Binkley Baptist Church, which from its founding was committed to being an interracial congregation that challenged racial segregation. There were Black collegiate athletes, but not in the South. Smith and Seymour shared the conviction that desegregating the basketball program at UNC could have national impact on college sports.

Smith began teaching the men’s Bible class at Binkley. He was an amazingly effective teacher, drawing members to the class and to the church, but Seymour had another ministry in mind for Smith. One day Seymour approached Smith and asked if he might consider stepping down as teacher and making the desegregation of the men’s basketball program at UNC his primary ministry. Seymour pledged his full support as well as the congregation.

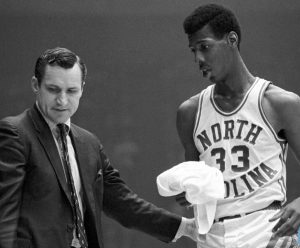

Dean Smith with Charlie Scott (Photo: UNC Basketball)

It was a harmless but wise move. Seymour’s encouragement gave Smith the inspiration and imagination to recruit Charlie Scott as the first Black player for Carolina’s varsity men’s basketball team in 1967. It was the beginning of a legendary career for Scott, and it marked a turning point for racial segregation in collegiate athletics. Scott helped bring the Tar Heel basketball program back to national prominence, reaching two Final Fours during his time at Carolina. More importantly, it was a decisive moment that led the way for the eventual desegregation of collegiate athletics.

When Howard Lee moved with his family to Chapel Hill in 1964, to enter graduate school at UNC, Lee, who is African American, was prevented from buying a home in a neighborhood that like lunch counters and water fountains were “for whites only.” The Lees became members of Binkley Baptist Church. With the encouragement and support of Seymour and the congregation, in 1969 Lee became the first Black mayor elected in a predominantly white city and the first Black mayor in the South since Reconstruction.

These and many more stories I heard from Bob Seymour and read in his book Whites Only: A Pastor’s Retrospective on Signs of the New South. Now that the courts, the legislatures and many churches are losing or have lost their conscience, I am left wondering whether the church can be a foretaste, a sign and an instrument of God’s reign here and now.

Bob Seymour

What I learned from Bob Seymour is that the church can be an agent of transformation for good and God by being more like Jesus — by having a vision of justice guided by wisdom. “Be wise as serpents and harmless as doves.” It is not only a gospel truth. It is a social strategy.

Curtis W. Freeman is research professor of theology and Baptist studies and director of the Baptist House of Studies at Duke Divinity School. His research and teaching explore areas of Free Church theology.

Note: Andrew Gardner has written a new book on the history of Binkley Memorial Baptist Church.

Related articles:

Racism and the evolution of Protestant support for private education | Analysis by Andrew Gardner

Remembering the struggle to integrate even ‘progressive’ Baptist churches in the 1960s | Analysis by Alan Bean

‘I remember repeating to myself: “I have the right to be here”’