Rep. John Lewis has bequeathed to the church a call to make “good trouble” and to stir up the gift that resides in us: faith in God and faith in each other. I pray the followers of Jesus are finally ready to claim our inheritance.

Aidsand Wright-Riggins

Willie Mae and Eddie Lewis raised 10 children as sharecropper parents outside Troy, Ala., in the 1940s and ’50s. John Robert was one of those children. Like many mothers of that generation, Willie Mae Lewis prayed daily that her children would stay out of trouble. A subject of many such prayers myself, I know that in a mother’s prayer for Black boys, “staying out of trouble” primarily meant the ability to keep one’s distance from the police and never having to spend a night in jail. By the time of his death, John Lewis had been arrested 45 times and spent many a night in jail.

Beginning with his arrest in Nashville, Tenn., for organizing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters while a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, John Lewis made it his practice to get into “good trouble” at every opportunity he could. He had fallen under the influence of the tinny, yet prophetic radio voice of the youthful Martin Luther King Jr., who was preaching and broadcasting out of Montgomery, Ala. Lewis resonated with King’s challenge to transform the dirty, dusty roads of injustice in the here and now rather than waiting oppression out to hopefully stride down streets of gold in the sweet bye and bye.

Along with Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and others, Lewis augmented his college studies by attending weekly training workshops led by James M. Lawson, whom Lewis later called “the architect” of the civil rights movement. Lawson had recently spent a year in prison for his refusal to participate in the draft as a conscientious objector. He then volunteered for three years of missionary service in India, where he studied Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence. Lewis absorbed Lawson’s insistence that Gandhi’s “satyagraha” (non-violently holding on to truth) or “soul force” and Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount were more than just effective civil and political tools for overcoming humiliation and dehumanization suffered under segregation. Lewis embraced the way of Jesus and soul force and embedded them in the core of his being for the rest of his life.

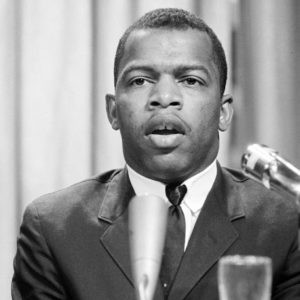

John Lewis, 1964. (Photo by Marion S. Trikosko, U.S. News and World Report, public domain image from United States Library of Congress)

The sacredness of all human beings and the fundamental unity of all of life propelled Lewis into trouble at every turn. He was maladjusted to going along with an evil system and threw his body into situations of division and discrimination to see what he could do about it. Many of us recall images of him standing on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Sunday, March 7, 1965.

On that Bloody Sunday, when many civil rights leaders and organizations thought Selma too dangerous to deal with, Lewis stood at the apex of the Edmund Pettus Bridge and stared into a sea of blue-clad Alabama state troopers. He refused to be turned around in his long journey toward freedom. Suddenly, that sea of blue closed around him and the rest of the faithful as waves of batons beat down on them unmercifully. John Lewis wore the scars of that brutal beating the rest of his life. Asked about whether he felt afraid on that bridge, Lewis, said, “No, I wasn’t afraid. I felt liberated.”

For Lewis, standing on that bridge in the face of overwhelming odds was not just a political act; it was a spiritual commitment. As we eulogize John Lewis, I pray the church inherits from him his fearless commitment to walk into good trouble. Systemic disenfranchisement, creeping militaristic totalitarianism, Christian nationalism and structural white supremacy are four deadly horsemen who barricade the bridge toward justice and human dignity in the USA.

Perfect love casts out fear, says 1 John 4:18. I pray the church loves Jesus enough to express and exhibit its conviction that at the core of creation is a Cosmic Companion who calls us to walk toward these ends. Making good trouble is an expression of our spirituality, not just our politics.

This work requires faith. Faith in God and faith in each other. John Lewis was a person of enormous faith. He had faith in a God who would ultimately bend the arc of the universe toward God’s purposive ends of truth, beauty, goodness and justice. For Lewis, every encounter, person or policy that seemed to contradict or contravene God’s goodness or God’s good ends was only an illusion. I believe one of the legacies Lewis leaves us is a story that stirs up our faith.

Lewis once wrote, “Faith, is being so sure of what the spirit has whispered in your heart that your belief in its eventuality is unshakeable. Nothing can make you doubt that what you have heard will become a reality. Even if you do not live to see it come to pass, you know without one doubt that it will be. That is faith.” To me, such confidence is what made this 5-foot-6-inch-tall bald guy so charismatic. It wasn’t his oratory or his good looks. It was his compelling and irresistible faith.

Congressman John Lewis

One of his last public acts of protest and solidarity was to stand with D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser at Washington’s 16th Street two-block-long art mural that boldly proclaims, “Black Lives Matter.” Having lived just long enough to witness what may be the dawning of the most impactful nonviolent movement in this country, Lewis stood on that mural and said, “I think the people in D.C. and around the nation are sending a mightily powerful and strong message to the rest of the world that we will get there.” What faith in God. What faith in humanity.

Everyone wanted to get a selfie with Lewis. And judging by social media this past week, just about half of America did. It seems just about everyone wanted to have whatever he had to rub off on them.

Lewis believed with every fiber of his being that love already had overcome hate, that every expression of evil could never stand. This made him powerful yet patient. This made him fight fiercely for freedom. Yet he found time to laugh and joke and never to take himself too seriously. He affirmed, “We are actors dramatizing our faith in the supremacy of one truth that no law, no centuries-old tradition, no military force, no military might, no matter how ferocious, could undermine the dictates of the divine.”

Lewis lived a long and productive life, more than twice as long as his spiritual father, Martin Luther King Jr. But length of days and fame were not what John Lewis lived for. More valuable than longevity and notoriety for him was faithfulness — faith that we are all children of the same omniscient Creator who clothed us in the garment of mutuality.

For Lewis, any pronouncement or practice of discrimination and division had to be an error, a delusion based on fallacious thinking, a distortion of the truth. His was a faith grounded in what he saw as a divine heritage that links us with every other human being and all creation. Such have we inherited from this proclaimer and policy maker who heralded the Beloved Community throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. May we go and do likewise.

Aidsand F. Wright-Riggins is a “retired” American Baptist minister, serving as acting executive director of the New Baptist Covenant, mayor of Collegeville, Pa., and executive director emeritus of the American Baptist Home Mission Societies.