Fundamentalist Christians are more likely than the rest of Americans to see advances by the LGBTQ community as a zero-sum game that proportionately erodes religious liberty for Christians, according to a new set of academic studies.

While many previous national surveys have examined Americans’ individual attitudes about LGBTQ acceptance and same-sex marriage, this new set of five interrelated studies looked specifically at how zero-sum beliefs influence such views.

The bottom line, researchers found, is that Christians in general but fundamentalist Christians in particular are more likely to perceive every gain by the LGBTQ community to come at the expense of the Christian community. The correlation is so strong that the numbers line up clearly, showing an almost exact perception of offsetting gains and losses.

“Even though Christians and sexual minorities are overlapping groups (the majority of LGBT individuals identify as Christian), many Christians fail to recognize this reality. Instead, they perceive a zero-sum relationship with LGBT people: believing that social advances for sexual and gender minorities are harmful and threatening to Christians,” reported Clara Wilkins and Lerone Martin of Washington University in St. Louis.

“Even though Christians and sexual minorities are overlapping groups (the majority of LGBT individuals identify as Christian), many Christians fail to recognize this reality. Instead, they perceive a zero-sum relationship with LGBT people: believing that social advances for sexual and gender minorities are harmful and threatening to Christians,” reported Clara Wilkins and Lerone Martin of Washington University in St. Louis.

Their team’s research was formally reported in the Journal for Personality and Social Psychology and later summarized in the online journal Religion & Politics.

Overall, American attitudes toward LGBTQ inclusion and support for same-sex marriage have been rapidly changing over the past decade — changing so rapidly that some researchers have declared this to be the fastest social change recorded in modern history. While that social change has swept through parts of the Christian community, opposing this change has become a rallying cry for the most conservative segment of American Christianity.

Opposing attitudes on same-sex marriage and LGBTQ inclusion have fractured congregations and entire denominations. Nowhere has this been more visible than in the United Methodist Church, which is in the midst of a pandemic-slowed schism that is largely about human sexuality. Thus, one of the five studies in the new research used United Methodists as a specific case study.

Behind all the angst over LGBTQ inclusion lies the reality of declining national influence for Christians and Christian culture in America. Even though a majority of Americans claim Christianity as their religious identity, those numbers are declining. Previous research has documented the fears Christians express about losing cultural influence.

“Christians may perceive that an America where same-sex marriage is legal is one in which they have lost their sway and are now victimized.”

“Christians in the United States may be particularly concerned about symbolic threats to their group given their declining social influence in American political and social life,” Wilkins and Martin noted. “For much of U.S. history, white Christians were a dominant force in deciding elections, enacting legal policies, and setting cultural norms, but significant demographic and cultural shifts have reduced their influence. Many Christians have come to see themselves as being on the losing side of the culture wars, and that loss was epitomized for some by the legalization of same-sex marriage.”

The researchers added: “For some, the core cultural understanding of what it means to be a moral Christian may increasingly be at odds with popular perspectives in the U.S. In other words, Christians may perceive that an America where same-sex marriage is legal is one in which they have lost their sway and are now victimized.”

This symbolic threat plays a key role in some Christians’ perceptions that any gain in cultural influence by the LGBTQ community equals loss of Christians’ cultural influence. They perceive the two realities as mutually exclusive.

Wilkins and Martin led five studies between July 2016 and December 2019.

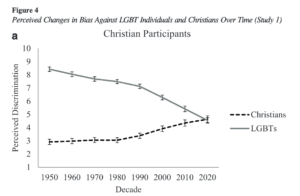

In the first study, Christians who identified as heterosexual and cisgender were asked what they perceived to be the amount of discrimination that Christians and LGBTQ groups faced in each decade from 1950 to 2020. Christians reported corresponding decreases in discrimination against LGBTQ persons and increases in discrimination against Christians.

For the current decade, Christian respondents ranked bias against Christians to be as severe as the bias against LGBTQ persons. “Christians also endorsed explicit statements pitting the groups against each other,” the researchers reported; for example affirming this statement: “As LGBT individuals face less discrimination, Christians end up facing more discrimination.”

“Christians also endorsed explicit statements pitting the groups against each other.”

For one of the studies, a subset of Christians was assigned reading material about how a decreasing Christian population in the United States is reporting greater concern about threats to their religious values. Respondents who were influenced by this reading material were more likely than others to then report anti-Christian bias and conflict between Christians and LGBTQ persons.

“Considering a society in which Christians are less dominant was sufficient to increase perceptions of Christians’ victimization and Christians’ perceived conflict with LGBT individuals,” the researchers reported. “This pattern was particular apparent among white conservative Christians surveyed.”

On the other hand, assigning survey participants advance reading on Scriptures related to acceptance — for example, John 8:3-11, in which Jesus choose not to condemn an adulteress — led to less perceived threats to Christians by the LGBTQ community among mainline Christians but did not change the attitudes of fundamentalist Christians.

Another study among the five sought to understand the influence of religious communities in shaping attitudes about LGBTQ inclusion. This was done by surveying members of United Methodist congregations before and after the February 2019 vote by the denomination not to allow the ordination of LGBTQ clergy or the blessing of same-sex unions.

“Before the vote, zero-sum beliefs were positively related to sexual prejudice, and that relationship became even stronger after the vote,” the researchers noted. “This suggests the vote likely sanctioned sexual prejudice and gave these Christians the freedom to express their bias more openly.”

This research was funded by a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust and as part of the Self, Virtue, and Public Life Project, a three-year research initiative based at the Institute for the Study of Human Flourishing at the University of Oklahoma.

Related articles: