By Bob Allen

A little-known federal law enacted to bolster the rights of religious minorities is less popular but more needed now than when it became law 20 years ago, the head of a broad coalition that worked for passage of the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act said Nov. 7 at a symposium assessing the legislation’s past, present and future.

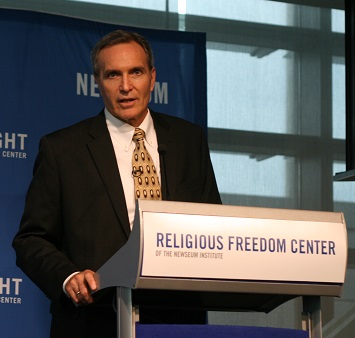

“I have long said that religious liberty is very popular in the abstract,” said Oliver “Buzz” Thomas, a religious-liberty attorney who advocated for passage of RFRA 20 years ago while working for the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. “It’s only in its application that we begin shouting at one another.”

In a keynote address at the daylong discussion at the Newseum in Washington, Thomas said it should come as no surprise that the law currently at the center of numerous lawsuits over Obamacare has grown less popular with the passage of time.

“It was the same way with the First Amendment,” Thomas said. “Widely acclaimed at its passage, more than a third of Americans now say that the First Amendment goes too far.”

“They like religious freedom for themselves, but they’re not so sure they like it for witches or Moonies or Muslims,” he said.

The story behind RFRA began in 1990, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Employment Division v. Smith that the Constitution did not protect the rights of Native Americans to use the controlled substance peyote in religious rites.

Thomas recalled that at the time media coverage didn’t consider it a big deal, because the religious use of a drug is not an issue that affects most Americans. But after reading the decision, it became clear to him that the ruling had broad implications for religious liberty.

Thomas recalled that at the time media coverage didn’t consider it a big deal, because the religious use of a drug is not an issue that affects most Americans. But after reading the decision, it became clear to him that the ruling had broad implications for religious liberty.

Prior to 1990, the Supreme Court had interpreted the First Amendment to mean that only governmental interests of the highest order could justify restrictions on the free exercise of religion.

The reversal prompted a coalition of groups ranging from the Southern Baptist Convention and Home School Defense Association to the United Church of Christ and Unitarian Universalists to support legislation that government “shall not substantially” burden a person’s religious exercise lacking a “compelling governmental interest” that is achieved by “the least restrictive means.”

“Those who would criticize the Religious Freedom Restoration Act must criticize conscience itself,” Thomas said.

Thomas said the three-year period between the Smith decision and RFRA saw religious freedom struggles for Amish families, Sikh construction workers, Orthodox Jews, evangelical Christians and virtually every religious minority.

“In America, somewhere that means every religion because we’re all a minority somewhere,” he said. “You may be a happy Baptist in north Alabama, but if you are in Utah you are in a different situation.”

Thomas said the Religious Freedom Restoration Act is about more than civil rights. “It’s about what it means to be an American.”

Prior to the Bill of Rights, Thomas said to enjoy full benefits of citizenship an individual had to be white, male, a landowner and “a particular kind of Christian.” At one time, for example, it was a crime in Virginia not to baptize your children into the Anglican Church.

“Let that soak in for a moment,” Thomas said. “That is our history.”

“Of course being an American today is about none of these things,” he said. “It’s not about race or gender or where we go to church or if we go to church. It’s about principles and ideals. In fact, there is no America without freedom of religion, press and speech.”

Thomas recalled Founding Father James Madison’s argument that the claims of conscience and religious liberty were “precedent” over the claims of civil society and secular government.

“They still are,” Thomas said. “In fact, they are more important today than they were 200 years ago, more important today than they were 20 years ago, as government has become more pervasive, more invasive, ubiquitous.”

“It’s all around us,” he said. “It’s in every part of our lives. They are reading our e-mails. They’re listening to our conversations. Government is everywhere in the United States today.”

“And our religions have become more diverse,” he continued. “That’s why it’s so important today. Diversity is out of the box now. We’re never going back to the days that I grew up in where diversity meant, in my little town in Tennessee, are you Baptist or Presbyterian?”

“These principles matter more now than ever,” Thomas said. “In fact they are the glue that holds us together as Americans — E Pluribus Unum.”

The Baptist Joint Committee, a religious-liberty watchdog group that represents 15 national and regional Baptist bodies including the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, co-sponsored the event with the Christian Legal Society, American Jewish Committee, Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations, Becket Fund for Religious Liberty and Religious Freedom Center of the Newseum Institute.