Mercer University researchers have identified a critical pastoral care need for leaders of rural churches: America’s farmers are in a mental health crisis.

Across all farmers surveyed in a Georgia sample, 82% reported a moderate level of stress according to the Perceived Stress Scale, a widely used assessment instrument that places respondents in one of three categories: low, moderate or high perceived stress.

Additionally, 49% reported being sad or depressed, 47% reported experiencing loneliness, 39% reported feeling hopeless and 29% reported thinking of dying by suicide at least once per month.

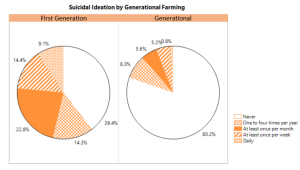

But looking more closely at the data shows farm managers and farmworkers are most stressed of the lot. And more specifically, first-generation farmers are in distress, with 61% saying they’ve thought about dying by suicide in the past 12 months, compared to 10% of generational farmers.

But looking more closely at the data shows farm managers and farmworkers are most stressed of the lot. And more specifically, first-generation farmers are in distress, with 61% saying they’ve thought about dying by suicide in the past 12 months, compared to 10% of generational farmers.

These are among the findings of new research conducted by the Georgia Rural Health Innovation Center, housed in Mercer University’s School of Medicine, and the Georgia Foundation for Agriculture.

Mercer, based in Macon, Ga., reported findings of two related surveys conducted in 2021-2022, the first of 500 farmers and the second of 1,651 farmers. For purposes of the research, “farmer” was defined as farm owners, farm managers, farmworkers, spouses and other farm-related roles such as accountants.

Farm owners were found to be the least stressed of the group, while those with daily duties on the farm often were the most stressed.

A Mercer report on the research quoted Trey Bouwsma, who began working on his stepfather’s commercial broiler and cattle farm in the northeast Georgia town of Comer at the age of 13.

“There were eight broiler horses that had to be walked up and down every day,” he said. “It would easily take me about eight hours a day, seven days a week to do this. I can probably cut that time in half now that I am older, but there are still no days off. You learn quickly that live animals do not care if it is a holiday or special event, tending to the animals is always the No. 1 priority.”

After going away to college and returning home, he now works as a liaison between a poultry company and a contract grower.

“I interact with poultry producers on a daily basis, and many producers vent to me about the struggles of being a farmer,” he said. “I believe part of my job is to listen and offer encouragement when I can. Whether it is livestock or crops, the Georgia farmer will always face multiple stressors. All farmers rely on things such as weather, which they have zero control over. There are so many variables; I honestly wouldn’t know where to start. Unfortunately, most of the farmers I know and come in contact with have a very high stress level.”

“Unfortunately, most of the farmers I know and come in contact with have a very high stress level.”

His wife, Morgan, agrees and hopes that the information gleaned from the survey will encourage legislators to develop policy that will make it easier for farmers to get help when needed, help first-generation farmers start farming without going into “unfathomable” debt and create a more equitable market for anyone wanting to farm, whether it be on a small or large scale.

“Farmers are one of our most treasured assets since they provide some aspect of many basic human necessities, but historically it seems that they have not been taken care of mentally, physically or financially,” she said. “If farming was easy, there would be a lot more people doing it. Instead, there is less than 1% of the population upholding the other 99% with all these things we need. It’s an expensive venture and risky work, especially as a first-generation farmer when you’re really starting out entirely on your own.”

The stress on first-generation farmers is heightened by the financial risk involved, Trey Bouwsma said. “Starting out with no family land, you pretty much have to pay to play. To raise chickens specifically, you’ve got to have a huge down payment or land to put up as collateral. People are putting up all their savings, any inherited land or money, and ending up with high interest rates all just to farm. You also are never guaranteed the next flock. The only real sense of job security is if you are performing well with each flock compared to other producers.”

The researchers note that one in seven Georgians works in agriculture, forestry or related fields. Yet researchers Stephanie Basey, Anne Montgomery, Ben West, Chris Scoggins and Lily Baucom found few previous studies on the mental health of farmers.

One previous study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that of 130 occupations across the U.S., farming had the highest rate of death caused by stress-related conditions and psychiatric disorders, as well as the third-highest suicide rate.

While there are many takeaways from the new research, there’s one message that stands out above all, Basey said. “If people only take one thing from this study, it needs to be the level of stress that first-generation farmers are facing. We’re at a crisis level.”

Related articles:

Let’s begin a conversation about the church in rural areas | Opinion by Brian Foreman and Justin Nelson

A lesson from 19th century North Carolina: Lost cause, lost opportunity | Opinion by Greg Jarrell