If you’re interested in fascinating yet random facts and trends about American religion and culture, follow Ryan Burge (@ryanburge) on Twitter.

Burge, who is an American Baptist pastor and a professor at Eastern Illinois University, loves to make graphs. And he posts them on Twitter several times a day for anyone who’s interested to see. Some of the data come from his own research, but much of the data come from his analysis of publicly available national surveys.

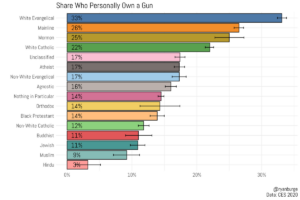

Since last week’s massacre at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, Burge has been looking into Americans’ beliefs and practices related to gun ownership.

For example, he learned that two-thirds of white evangelicals do not own a gun — perhaps not what would be expected from a group that largely supports the gun lobby and a broad interpretation of the Second Amendment.

For example, he learned that two-thirds of white evangelicals do not own a gun — perhaps not what would be expected from a group that largely supports the gun lobby and a broad interpretation of the Second Amendment.

One of the areas where Burge excels and offers insights not readily available anywhere else, though, is on the differences between white evangelicals and other Americans, especially as it relates to current issues and politics.

In a recent post, Burge created a graph to show how various categories of Americans see their own views in relation to Democrats and Republicans. He charted national data in which people were asked to place themselves and both parties on an ideological scale, with one being “very liberal” and seven being “very conservative.”

Most groups see themselves somewhere between the ideology of the two parties, but five groups do not: Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, agnostics and white evangelicals. Over the past six years, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and agnostics have identified their own ideology almost in parallel to what they see in the Democratic party.

On the other hand, though, white evangelicals stand out from all other Christian groups by their close identification with the Republican Party. Burge explained: “White evangelicals see no space between them and the Republican Party.” As the graph shows, in five of the past six years, white evangelicals place their views and the Republican Party’s views in near-exact alignment.

On the other hand, though, white evangelicals stand out from all other Christian groups by their close identification with the Republican Party. Burge explained: “White evangelicals see no space between them and the Republican Party.” As the graph shows, in five of the past six years, white evangelicals place their views and the Republican Party’s views in near-exact alignment.

But white Catholics, non-white evangelicals and mainline Protestants share a different pattern in which they view themselves in the near-center, with Democrats to the left and Republicans to the right — usually with lots of space between the viewpoints.

No other religious group — not even Mormons — identify so closely with the Republican Party.

Much has been written about the close alignment of white evangelical voters and the Republican Party, but there’s a parallel trend that shapes understanding of this phenomenon: The aging of the white evangelical base, which means the aging of the Republican Party base as well.

For several decades, demographers have predicted a massive demographic change that could have the potential to reshape national politics and religion. That change includes the reality of a non-white majority population and the continued growth of a non-religious population.

While these changes are indeed becoming reality, they are happening slowly and with some unexpected twists and turns.

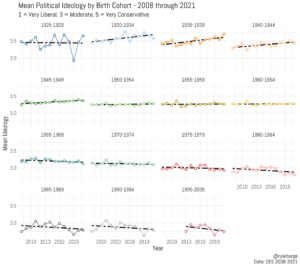

However, a recent graph created by Burge shows the undeniable trend that younger generations of Americans not only begin with more liberal views than their parents and grandparents but continue to grow more liberal from there. He analyzed data on Americans’ ideology from 2008 to 2021.

However, a recent graph created by Burge shows the undeniable trend that younger generations of Americans not only begin with more liberal views than their parents and grandparents but continue to grow more liberal from there. He analyzed data on Americans’ ideology from 2008 to 2021.

For generations, conventional wisdom has said people become more conservative as they age. But Burge says that’s no longer true: “This data tells a nuanced story. For those born between 1930 and 1949, they did move rightward between 2008 and 2021. 1950-1964 saw no change at all. Those born in 1965 or later have moved to the left between 2008 and 2021.”

From 1965 forward, Americans generally have started out with less conservative views than their forebears and instead of growing more conservative with age have grown slightly more liberal. This is the opposite of the trends that shaped those born from 1925 to 1964.

Ryan Burge

The change actually began with those born in 1950 and later who were the first generations to hold steady in their ideological views rather than growing more conservative with age. Among those born from 1950 to 1964, the trend line is flat.

This is not to say all young people today are more liberal than previous generations, just that the average younger person today follows that trend. This has important implications for both politics and religion and could help explain why conflict in congregations over hot-button issues like LGBTQ inclusion appears to be generational in nature.

In addition to his voluminous Twitter feed, Burge also has written a new book titled 20 Myths About Religion and Politics in America. He describes the book as “a collection of 20 self-contained chapters that explore a lot of things that people believe about religion and politics that is just flat out wrong.”

Related articles:

Ryan Burge sifts the data to paint an evolving portrait of the ‘nones’