The Southern Baptist Convention currently faces one of the greatest tests ever of its internal governance while also fending off serious accusations of mishandling sexual abuse claims.

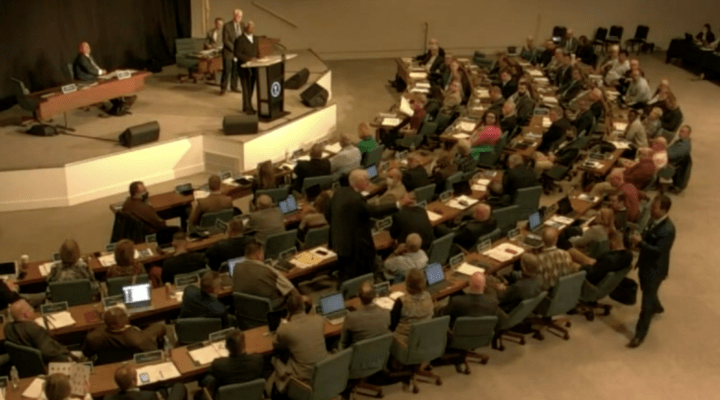

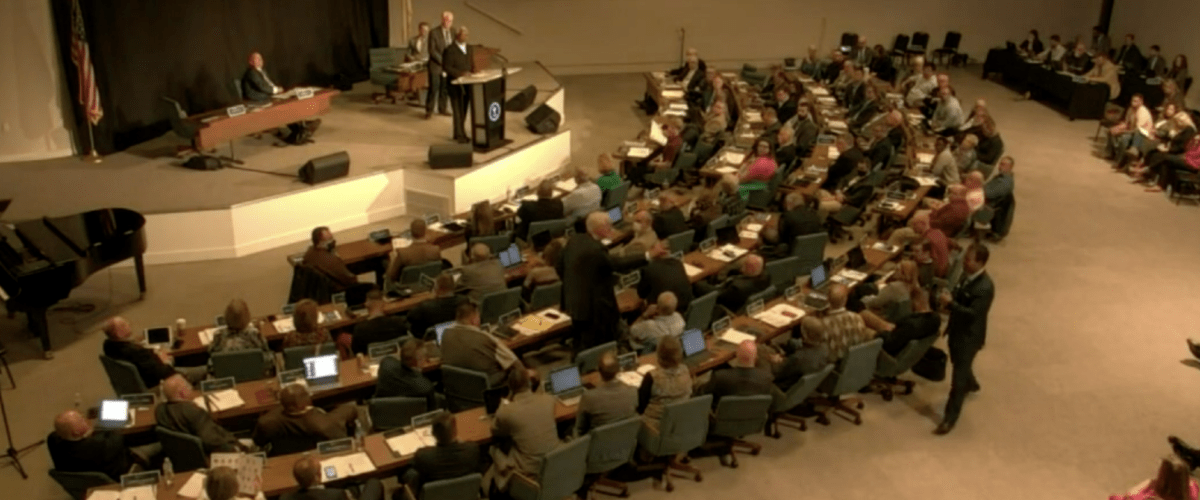

This dual problem consumed the Sept. 20-21 meeting of the SBC Executive Committee with debate and questions and parliamentary maneuvers more complex than most Baptist church business meetings ever have seen — and with no resolution despite hours of debate.

Parliamentarian Barry McCarty stood closely behind or beside Executive Committee Chairman Rolland Slade at every step of the committee’s two days of debate.

Throughout the meetings, professional parliamentarian Barry McCarty stood over the shoulder of Chairman Rolland Slade, a California pastor, directing most every move to ensure proper procedure. But even that wasn’t enough to keep order, as the 86-member body struggled to feel secure in doing the thing messengers to the SBC annual meeting had instructed them to do three months earlier.

At that June meeting, the convention in session — which in SBC governance is the highest authority — rebuked the Executive Committee’s attempt to hire a third-party investigator of its own alleged mishandling of sexual abuse claims. Instead, messengers demanded that the new SBC president, Alabama pastor Ed Litton, name a special task force to oversee the investigation and report back to the full convention — not to the Executive Committee.

But the Executive Committee holds the purse strings required to fund the task force’s work — including its contract for up to $1.6 million with the consulting firm Guidepost Solutions. Further, the task force and Guidepost together have asked Executive Committee members and staff to waive attorney-client privilege so that anything they say during the investigation cannot be shielded from public release. Such a guarantee is essential to the transparency needed on such a volatile issue as covering up sexual abuse, the task force has said.

Members of the Executive Committee and staff leaders of the Executive Committee aren’t keen on that request, however, believing such a waiver could imperil them individually and collectively depending on the results of the investigation. The most common argument for this view is that committee and staff members have a “fiduciary responsibility” to the Executive Committee that supersedes the will of convention messengers.

SBC hierarchy

Yet declining the waiver — whether the right thing to do as a fiduciary or not — would put the Executive Committee in the awkward position of inverting the hierarchy of the SBC’s form of congregational governance. By most accounts, the Executive Committee and its staff must do what the convention in annual session directs them to do.

Baptist pastors in training are taught in seminary that the head of the Baptist denomination is the local congregation — which sends messengers to annual meetings to direct paid staff and volunteer committees in their ministries.

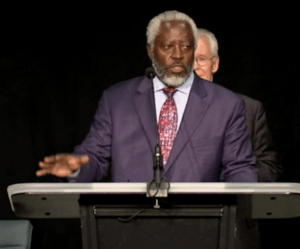

Ronnie Floyd (Baptist Press)

By questioning the wisdom of accepting the convention’s request to waive attorney-client privilege, Executive Committee President Ronnie Floyd has been labeled by some as a wanna-be dictator, daring to invert the governance of the convention itself.

A Twitter commentator named SBC Fact Check tweeted Monday night: “If the @SBCExecComm can ignore the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention on this issue, can the Executive Committee also ignore the churches on other issues? Trustee nominations? Confessional commitments? Budgets? Presidential elections?”

And that is the rub: Does the Executive Committee have any ability to go against the will of convention messengers? And if they choose to do so, what will be the consequences in public opinion and at next year’s convention?

Floyd opened the two-day meeting with an address in which he said “The SBC Executive Committee stands against all forms of sex abuse, mishandling of abuse, mistreatment of victims and any intimidation of abuse survivors in every Southern Baptist church, association, state convention, entity and affiliated organization. As president and CEO of the SBC Executive Committee, I encourage the members of the SBC Executive Committee to work with the Sex Abuse Task Force and the independent review firm in every way possible, but within our fiduciary responsibilities as assigned by the messengers.”

What sexual abuse survivors and allies and Southern Baptists demanding transparency heard most was the “but” at the end of the sentence.

Attorney-client privilege

Debate on how to respond to the sexual abuse task force began with a recommendation from the Executive Committee officers — a recommendation that appeared unsatisfactory with the body as a whole. Further complicating the debate was the fact that about one-fourth of the elected body is newly elected members who were attending their first meeting.

Further complicating the debate was the fact that about one-fourth of the elected body is newly elected members who were attending their first meeting.

Written in the form of a resolution, that four-paragraph recommendation declared belief that “there is a workable path to achieve a full and fair investigation that does not sacrifice (the Executive Committee’s) responsibilities or jeopardize the future work of the Southern Baptist Convention.”

The resolution would have authorized payment of Cooperative Program offerings (the only money the SBC has other than designated gifts) to fund the task force and its third-party investigators, Guidepost Solutions. However, it would not have resolved the question of waiving attorney-client privilege, saying instead that funding would be “subject to the achievement of an acceptable agreement on a way forward taking into account the (SBC) motion and the fiduciary obligations” of the Executive Committee.

It further would have empowered Executive Committee officers “to work on behalf of the full board in order to expeditiously reach a path forward for the important work of the investigation,” seemingly not requiring further consultation with the full body.

And in the final clause, the officers’ proposed resolution curiously said the Executive Committee “humbly appeals” to the Sexual Abuse Task Force “to work in cooperation with us to expeditiously conduct a third-party review and provide the desired answers for Southern Baptists.”

Whatever might have been intended by the language, it appeared to some to be another attempt to put the cart before the horse. The convention at large already authorized the investigation and said the Executive Committee and its staff should cooperate with them. Further, convention messengers explicitly revoked the Executive Committee’s attempt to drive the investigation and said the task force reports to the convention, not to the Executive Committee.

Whatever might have been intended by the language, it appeared to some to be another attempt to put the cart before the horse.

‘We cannot direct the task force’

This underlying tug-of-war about who will report to whom and who can demand what of whom and who has a fiduciary responsibility to whom was ever-present in the public debate over both days but especially in the five-hour session Tuesday afternoon.

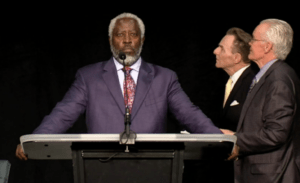

Around 4:30 p.m. on Tuesday, half an hour after the series of meetings was scheduled to end and no apparent solution was rising above the intractable debate, Executive Committee Chairman Slade took the microphone for an impromptu address.

One of the first things he said was this: “We cannot direct the task force.”

Then he launched into a 20-minute unscripted speech, for the first time leaving the parliamentarian standing speechless behind him.

Rolland Slade addressing Executive Committee members while Ronnie Floyd and Barry McCarty look at text on nearby monitor.

“We were tasked with seeing this through, getting this done,” he declared. “Hear me clearly: We are going to leave here not having gotten it done. And truly, brothers and sisters, that is not going to be acceptable to the messengers of the Southern Baptist Convention, and it should not be.”

He continued: “I’ve had a bit in my mouth all day. We have to get this done. We’ve been tasked with getting it done. We’ve been tasked with working together, and we’re finding it difficult working together. If we do not show unity, we are … dishonoring our Lord and Savior. … I’m trying my best to be a gentleman, but I’m a kid from the hood. … Here’s what I know to have been a fact: We have been distracted from the doing the work the Lord put on our hearts … We ought to be sharing the gospel, and we need to be taking care of those who have been abused and survived sexual abuse. What we’ve been engaged in — we’ve been going back and forth, back and forth …. We have wasted this time.”

Then he spoke to the urgency of the investigation with an appeal for transparency: “There are some things over 20 years that have happened, and we need to find out what those things are. … I believe we all have skeletons in our closet. The question is whether we have meat on our skeletons … Here is an opportunity for us to throw open the doors … and say, ‘Come and investigate … see what it is we have done.’ … We don’t need to protect the report. … We need to get off this merry-go-round of amendments and all that kind of stuff, and I’m utterly confused.”

Silence fell over the room for the entirety of Slade’s speech. And for a few minutes afterward, it appeared he might have broken the logjam and called the group back to the officers’ original recommendation — even while acknowledging it was not perfect. Amendments already on the floor were withdrawn to clear the way, but at least one member objected, and a substitute motion that had been proposed by Melissa Golden of Alabama came back into play.

Silence fell over the room for the entirety of Slade’s speech.

After more maneuvering, the group ultimately replaced the officers’ resolution with Golden’s substitute motion that authorized up to $1.6 million in funding for the investigation and directed Executive Committee officers and members of the task force to “agree” on a way forward without a complete waiver of attorney-client privilege and then to bring that proposed way forward back to the full Executive Committee no later than Sept. 28.

Abuse survivors and allies dismayed

Before, during and after the meeting, sexual abuse survivors and their advocates — along with other SBC pastors and leaders — urged the Executive Committee to do what convention messengers had asked and expressed dismay at the chaos and outcome of these two days of meetings.

All but two hours of the meeting — a portion held in executive session on Monday — was livestreamed on the internet, and SBC victims of sexual abuse and their allies were both in the room and watching and commenting in a running thread on Twitter.

Grant Gaines, the Tennessee pastor who made the motion in June to create the special task force, tweeted Tuesday afternoon: “Executive Committee trustees, I’m thankful for many of you who were brave today, but far too many of you buckled under the pressure and influence of Ronnie Floyd.”

Russell Moore, former head of the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and one of the key advocates for repentance and reform, tweeted: “To those of you who have been bullied and intimidated, had your names and your reputations destroyed by those in ecclesial power because you spoke up about abuse, or stood with those who did: Jesus is far better than this. And he’s watching. Goodbye to all of that.”

“I’m so frustrated, I’m sobbing.”

Beth Moore, the popular Bible study teacher and author who made headlines earlier this year by announcing she’s leaving the SBC, tweeted in response to Russell Moore: “I’m so frustrated, I’m sobbing.”

Hannah Kate Williams, an abuse survivor who has filed a large-scale lawsuit against the SBC alleging a conspiracy to cover up abuse, was present at the meeting and tweeted: “EC member just said that the SBC is more important to protect than the messengers and ultimately than survivors.”

‘In Christ Alone’

Earlier, in an odd twist of painful irony, Williams had noted the unfortunate selection of music at the meeting: “It’s well known that ‘In Christ Alone’ was a song played on the computer speakers during my abuse. Being in a room with people who enabled and dismissed my abuse where they’re singing it in unison … I’m just so thankful Jesus is bigger than my worst pain.”

The person who apparently chose that song for the group quickly apologized to Williams via Twitter, an apology she accepted. However, apart from Williams’ own history with the song, it is one of the most theologically controversial worship songs of the last two decades.

The song as originally written espouses a view of penal substitutionary atonement, popular with many Calvinists and evangelicals but hotly disputed in the larger Christian community today. In 2013, Presbyterian Publishing decided to exclude the song from its new hymnal because the authors would not allow them to change one line that says, “as Jesus died, the wrath of God was satisfied.” The Presbyterians wanted to change it to, “’Till on that cross as Jesus died, the love of God was magnified.”

Sexual abuse survivors inside and outside the SBC also has something to say about the wrath of God, which they believe the SBC and other religious bodies are calling down upon themselves for their refusal to repent and repair the damage done by decades of unacknowledged abuse cases in churches.

Related articles:

SBC Executive Committee hires a firm to investigate itself and report findings to itself