Black churches became centers of political engagement during the 19th century when Black Christians determined to achieve the full benefits of citizenship in U.S. society, scholar Nicole Myers Turner said during a Baptist History and Heritage Society webinar.

Racial politics was driven “by the need to access resources that free Black people had been denied and a deep sense that Black freedom and equality must be recognized,” she said. “There was a development of this resistance to being marginalized in the post-emancipation period.”

Nicole Myers Turner

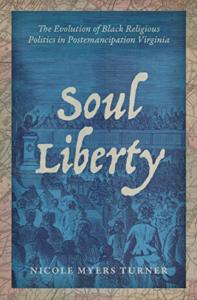

Myers Turner, an assistant professor of American religious history at Yale University, lectured on her 2020 book, Soul Liberty: The Evolution of Black Religious Politics in Postemancipation Virginia. The presentation marked the third installment of the society’s ongoing “Making Black History Public History” project and was hosted virtually by First Baptist Church in Hampton, Va., and its pastor, Todd C. Davidson.

The July 7 address included summaries of case studies from the book detailing the evolution and effectiveness of Black religious political advocacy, the emerging voice of women within the Black church, the ascendance of the pastor in church leadership, and the influence of Black theological education in those gender and ministerial developments.

“Whenever we think about Black churches, it’s not far behind that we hear about someone like Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights movement. … I wanted to tease out, how did Black churches become these spaces?” the author explained.

The answer traces back to the late 1880s, when John Mercer Langston became the first Black Virginian elected to Congress.

John Mercer Langston

Black churches and associations, previously isolated over issues of polity and theology, began to cooperate to address mutual social and political challenges. By the time Langston ran for the U.S. House of Representatives, he was able to capitalize on those widespread, interconnected associations for support.

“We see a transition in leadership where Black church networks become key for organizing politically,” Myers Turner said. “It’s the arrival of the Black church.”

Black churches and associations, previously isolated over issues of polity and theology, began to cooperate to address mutual social and political challenges.

The use of the term “soul liberty” in the title of the book, she added, refers to that achievement and to the Black church’s pursuit of religious freedom, equity and justice.

Women also were seeking that freedom and reached it to a degree with the congressional campaign, she said. “Langston incorporated women in his organizing. They could not hold office, but they could organize and help Black candidates.”

A pivot point for women also was documented in a Virginia congregation’s handling of an unwed mother and her ultimately unsuccessful appeal for church reinstatement in the early 1880s.

Women in the congregation were able to initiate a series of conversations and committee hearings challenging the traditional practice of restoring men to membership in such cases, but not women.

“We can see that even the presence of this conversation reflected how women’s voices were gaining strength. Women started to call out these inequalities and have the church’s attention,” Myers Turner said. “So even though (the woman’s) claim was not successful, what is remarkable about this case is that in the church meetings, women’s voices were being heard and they were able to be included in this process. Whereas in the past, they were the ones being disciplined and they had no voice.”

“We can see that even the presence of this conversation reflected how women’s voices were gaining strength. Women started to call out these inequalities and have the church’s attention,” Myers Turner said. “So even though (the woman’s) claim was not successful, what is remarkable about this case is that in the church meetings, women’s voices were being heard and they were able to be included in this process. Whereas in the past, they were the ones being disciplined and they had no voice.”

The case also demonstrated the ongoing rise of the pastor as the leading authority in Black churches, in this instance deciding that unwed mothers would be disciplined while men would not be, she said. “Whereas the church used to make communal decisions, now the decision rested with the pastor. This is a transformation that happens over the course of the 19th century.”

The ascendance of the pastor also was reinforced through the development of theological education for Black ministers during this era, she said.

Myers Turner cited Branch Theological Seminary, an institution founded by the Virginia Diocese of the Episcopal Church to educate Black ministers and to maintain segregation between white and Black churches. “This is one of the places where we start to see theological education and its gender components, the idea that theological education would be for men only.”

But even the theological education of Black men was considered dangerous by some because it posed “a real danger to white supremacy that Black men would be trained and elevated to ministerial leadership,” she said.

The lack of educational opportunities for Black women became increasingly seen as perilous by Black church leaders and educators, Myers Turner said. “By the late 1880s, early 1890s, there starts to be this idea that education is one of the ways to preserve for Black women a sense of dignity and protection from violence that might happen if they were out working in the homes of white men.

“So we can start to see that Black ministerial leadership is established in theological education, and it also becomes a model of protection of Black women. The minister becomes a protective figure over Black women through the argument of education.”

Todd Davidson

In his response to the lecture, Davidson said the history of Black church activism has been alive and well in the churches he has served, and he lamented the theological differences that keep Black churches from doing more together.

But he added that Myers Turner’s book demonstrates the importance of churches diligently maintaining congregational histories.

“Churches need good historians or to partner with local academic institutions to chronicle this kind of history in the local church,” he said.

Myers Turner, who scoured church and convention minutes and local church archives and histories in her research, said she always urges congregations to preserve records and to record members’ experiences for future generations.

“We do need to partner more around oral histories and around church record keeping. There is so much history to be recorded through church members and also from churches preserving documents. We can’t keep telling their history without them.”

Related articles:

Meet the Baptist pastor who helped cultivate the Lost Cause narrative

Baptist missionaries exported white supremacy to Brazil alongside the gospel, historian says

Baptist History and Heritage Society receives grant, will launch new webinar series