Churches must become allies in the fight against hunger by shedding stereotypes around food insecurity and by avoiding pitfalls of toxic charity and scarcity thinking, panelists advised during a Cooperative Baptist Fellowship seminar.

The pandemic has made it especially difficult to focus on abundance and, in turn, on wanting to help others, said Eugene Cho, president of Bread for the World, a CBF partner organization. His taped remarks opened “Food Insecurity: How Congregations Are Responding (And Can Respond),” which was livestreamed Oct. 19.

Eugene Cho

“It has been an incredibly hard, challenging year and the temptation, if you’re like me, is to focus all my attention on me, on my family, on my church,” Cho said. “This is why there is a challenge with the scarcity mentality, placing ourselves as the most important priority.”

That perspective can create a scarcity of willingness to directly serve those in need and advocate for them to government leaders, he said. “But as followers of Christ, as the ‘Capital C Church,’ we’re called to not only just love ourselves because God loves us, but to love our neighbors.”

Andy Hale, CBF’s weekly podcast host and senior pastor of University Baptist Church in Baton Rouge, La., moderated the gathering that included ministers from congregations known for their hunger ministries: Bradley Boberg, senior pastor of Ox Hill Baptist Church in Oxon Hill, Md.; Michelle Carroll, associate pastor for missions at First Baptist Church at the Singing Bridge in Frankfort, Ky.; and Suzanne Hooie, minister of missions and community ministry at First Baptist Church in Dalton, Ga.

Their discussion ranged from the logistical and social challenges of addressing food scarcity, to the misunderstandings many have about those who experience hunger, theological motivations for engaging in the work and advice for churches that may be considering launching food ministries.

Michelle Carroll

According to statistics provided by CBF during the gathering, food insecurity is defined as insufficient access for individuals and families to lead active, healthy lifestyles.

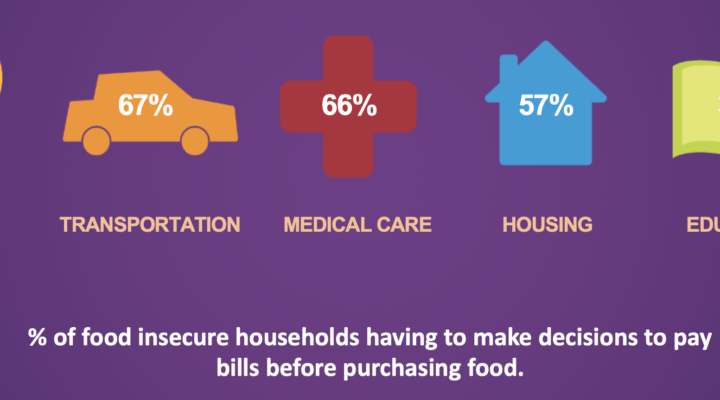

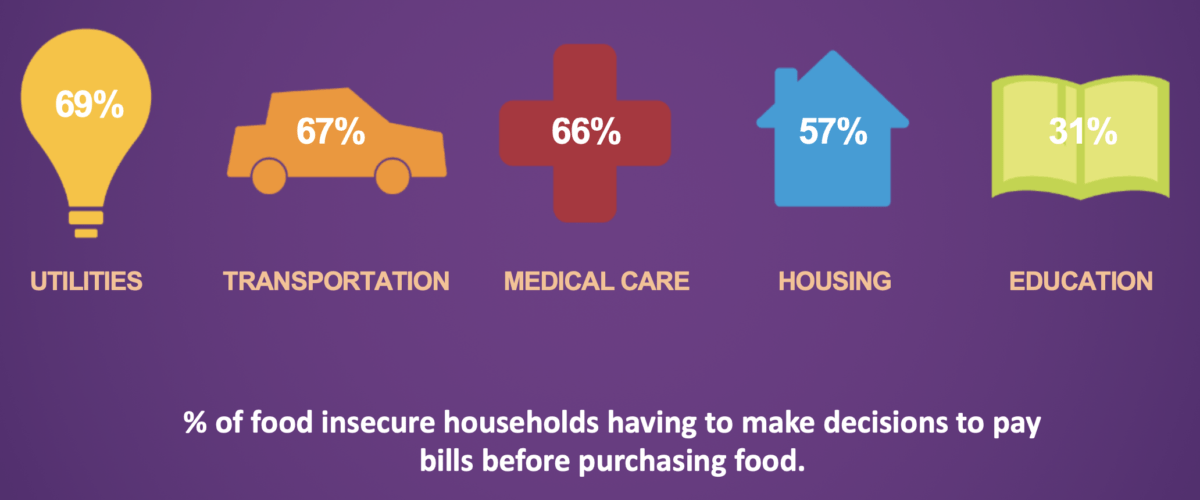

“Food insecurity may reflect a household’s need to make trade-offs between basic necessities (such as housing or medical bills) and purchasing food.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Americans facing food insecurity shot up from 35.2 million to 42 million, which includes 13 million children, according to numbers from Feeding America provided during the gathering.

In addition to children, those hit hardest by food insecurity include the elderly, low-income and ethnic minorities. “Individuals already at the margins face the most severe consequences of food insecurity.”

The trends should inspire not only involvement in food pantries and other direct ministries but also dedicated advocacy to pressure government to combat hunger, Cho said.

“We have to urge our nation’s leaders that they, too, have a responsibility to help end hunger in our nation and frankly around the world. We believe we can urge our leaders to be moral, to be just, to be compassionate when there are people experiencing hunger.”

But hunger ministry is fraught with pitfalls that churches and ministers must be vigilant to avoid, the panelists said.

Bradley Boberg

One of the biggest is a church or ministry believing it knows what’s best for those it seeks to serve, Boberg said.

“It’s easy for us to assume we know the need of our neighbors and that we know how to address all the needs of our neighbors,” he warned. “The need is often nuanced, and the solution is often even more complex. We have to listen to our neighbors and to our partners in ministry and work toward solutions.”

First Baptist in Dalton operates a ministry that provides food to children and youth on weekends and during holidays when subsidized school meals are unavailable, Hooie said. One of the challenges is being sensitive to the fact that, for teens especially, getting free meals can be embarrassing.

“It’s a challenge to serve them without taking way any dignity,” she said.

Misconceptions about those who face food insecurity also must be overcome, Hooie added. “I think people are surprised by the people who live right beside us who are hungry.”

Suzanne Hooie

First Baptist’s food ministry serves a school a half mile from its campus, which sometimes leads to astonishment among members when they realize the hungry live in the very neighborhoods surrounding the church, she said. “And I think a lot of people are surprised that we have elders who, for whatever reason, don’t have access to cooked meals or easy access to food.”

People also typically fail to grasp that food insecurity refers not only insufficient quantities of food, but also to the unavailability of quality groceries, Carroll said. “Too often, the junk foods and the super-processed foods are the cheapest and easiest things to get, especially when you get into food deserts where convenience stores are their closest food access.”

But faith is the motivation to take on whatever difficulties are presented in hunger ministry, Boberg said.

Matthew 25 confirms that “when we care for other people we are also caring for Jesus,” he said. “But it’s deeper than that, as the Old Testament also states that this idea of helping individuals dealing with food insecurity and those who are hungry is deeply ingrained in Jewish culture and society and lifestyle. Isaiah 58 and Ezekiel 18 both address this issue. We need to be people who are helping individuals who are hungry, who are thirsty, who are in need, and it’s a part of who we are.”

Churches that want to venture into hunger ministries should begin by researching local needs and collaborating with others already engaged in the work, he said.

While the program at Ox Hill Baptist serves thousands through partnerships including the Boys and Girls Club, it started small, Boberg said. “So, for us it was doing all that groundwork to make sure we were doing what was right.”

Related articles:

Want to help slow immigration to the U.S.? Address global hunger

It’s tough being a pastor on World Hunger Sunday, but it’s harder to be hungry | Opinion by Brett Younger