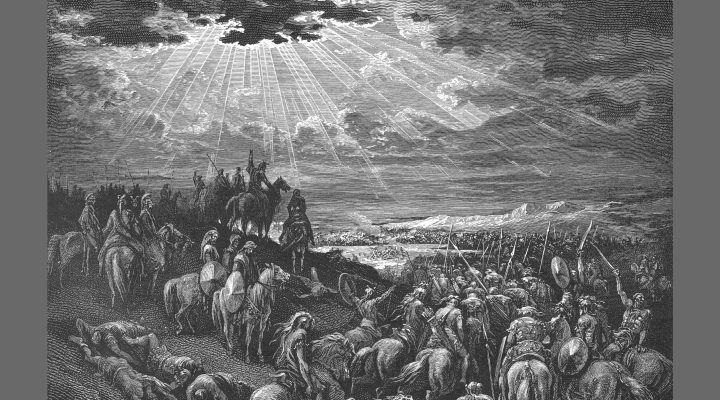

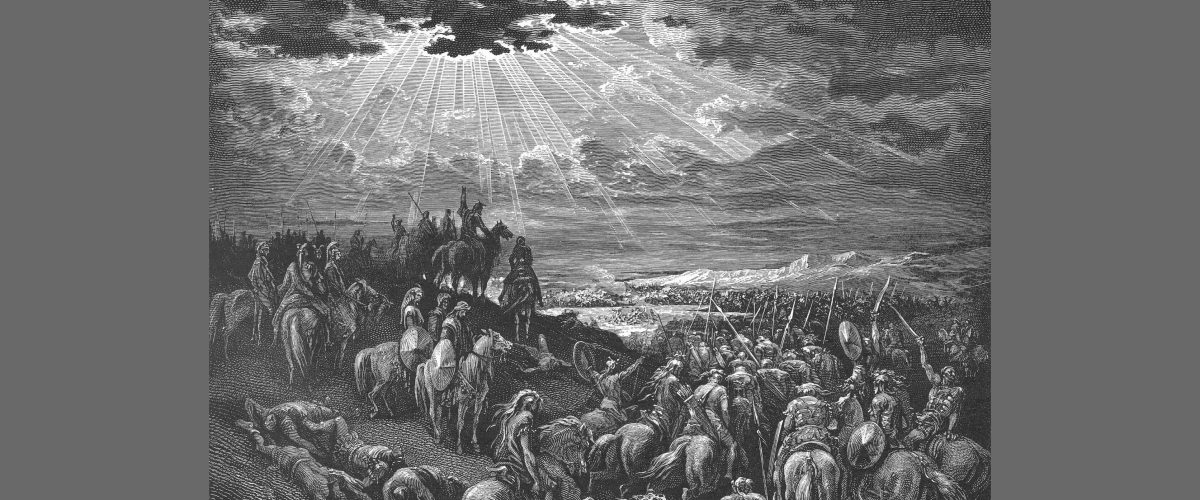

When I was an early adolescent, I decided to read the Bible straight through. I had been exposed to carefully curated snippets of Joshua, but the full genocidal thrust of the narrative was a revelation. I couldn’t help feeling sorry for those poor Canaanites, driven out of their native land so the children of Israel, after 40 years of wilderness wandering, could find a place to land. It seemed unfair.

And yet, there it was in black and white.

I concocted a zero-sum solution. There wasn’t room for everyone in the land of Canaan. So, if Israel found a home, somebody had to surrender their property.

My facile solution to the genocidal bits of the Bible held up pretty well until I realized universal compassion, love and forgiveness are central to the teaching of Jesus.

In the churches of my youth, the genocidal biblical texts received very little attention, and the radical ethics of Jesus fared little better. The moment we consider the implications of loving our enemies, we can’t help thinking, “But what about Joshua?” This works in reverse as well. At least it does for budding Christians, like me, who had decided to read the Bible straight through. I call it the Jesus-Joshua problem.

“The moment we consider the implications of loving our enemies, we can’t help thinking, ‘But what about Joshua?’”

The traditional solution doesn’t work

In his book The God I Don’t Understand, Christopher J.H. Wright “solves” the Jesus-Joshua problem by defining God’s commands to Joshua as an expression of divine justice. The Canaanites, the Bible reports, were exceedingly bad people. Not only were they sexual deviants, they sacrificed their own children to cruel gods. Of course, as the book of Deuteronomy freely admits, the Israelites weren’t much better. And, as the story of the flood in Genesis suggests, God came perilously close to wiping out the entire race. So, if God limited the general slaughter to the Canaanites, we can interpret God’s constraint as a severe mercy.

But this doesn’t work. Even if every adult man and woman in Canaan richly deserved to be butchered like hogs, what of the children? What kind of a God would sanction, let alone mandate, the wholesale slaughter of helpless infants (to say nothing of their parents)?

In his Commentaries on the Book of Joshua, John Calvin admits that, all things being equal, it would seem “arrogant and barbarous” and “contrary to the feelings of humanity” for the Israelites to “trample on the necks of kings, and hang up their dead bodies on gibbets.” However, the sage of Geneva argues, since the cruel deed was carried out at the command of God Almighty, it must not be questioned.

Jesus appears to disagree with Calvin’s assessment:

Is there anyone among you who, if your child asked for bread, would give a stone? Or if the child asked for a fish, would give a snake? If you, then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good things to those who ask him! (Matthew 7:9-11)

Jesus takes it as self-evident that God is infinitely more loving, more forgiving, and more compassionate than we are. This is why we can pray with confidence. At the very least, we can safely assume that God is as kind and loving as we are.

“Jesus takes it as self-evident that God is infinitely more loving, more forgiving, and more compassionate than we are.”

It isn’t enough to refrain from butchering our neighbors, Jesus says. We must love them. We must forgive them. We must pray for them. We must feed them when they are hungry, care for them when they are sick, visit them when they get locked up. No exceptions. (You can understand why the core teaching of Jesus is generally avoided in sermons and Sunday school lessons.)

We may fall short of this lofty standard, but God does not.

What if the violent conquest of Canaan never happened?

For the past century, Old Testament scholars have crafted an elegant solution to the ethical problems associated with the conquest of Canaan: It didn’t happen. No conquest, no genocide. No genocide, no Jesus-Joshua problem!

So, if Canaan wasn’t settled by bloody conquest, how did the people of Israel get there? Theories abound. Some posit a gradual migration of Semitic tribes. Others suggest the people who came to be known as “Israel” always had lived in the region.

Scholarly debate on the subject was revolutionized by the discovery of the “Amarna Letters” in Egypt. Discovered in the late 19th century, these letters provide a window into the practical workings of the Egyptian Empire between 1360–1332 BCE.

The Amarna letters make clear that thousands of slaves were routinely shifted from Canaan to Egypt and back again as economic needs evolved. A number of dates have been surmised for the biblical Exodus from Egypt, but most scholars agree the biblical narrative cannot be taken literally. In an article in the Journal of Biblical Literature, Ronald Hendel argues that between 1479 and 1148 BCE, “the land of Canaan was a province of the Egyptian empire.”

To illustrate the harsh reality of the Egyptian imperial project, Hendel shares this boast from Ramesses III (1186-1154):

I have brought back in great numbers those that my sword has spared, with their hands tied behind their backs before my horses, and their wives and children in tens of thousands, and their livestock in hundreds of thousands. I have imprisoned their leaders in fortresses bearing my name, and I have added to them chief archers and tribal chiefs, branded and enslaved, tattooed with my name, and their wives and children have been treated in the same way.

When Egypt’s grip on the region eventually loosened, bands of Canaanite slaves almost certainly migrated back to their ancestral home and, Hendel surmises, elements of the Exodus account may be rooted in this process.

Narratives shaped by helpless suffering

So, if the accounts in Exodus, Deuteronomy and Joshua shouldn’t be taken as sober history, how did these stories emerge? They certainly weren’t invented out of whole cloth. More likely, the stories that now comprise the biblical book of Joshua originated as distinct units cherished by the various tribes of Israel. Only later, in a process covering several centuries, were these narratives woven into a single connected story.

Most Old Testament scholars believe the Deuteronomic History (Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) assumed its present form in the years just before, during and immediately following the Babylonian captivity in the sixth century BCE.

“It all came down to idolatry.”

The people of Judah wrestled with a single perplexing question: If we are God’s chosen people, why have we been reduced to ruin? It all came down to idolatry. As the Deuteronomic history makes clear, the children of Israel committed to loving and obeying Yahweh alone. Instead, they were seduced into idolatrous alliances with the neighboring nations.

All of which explains God’s insistence that the nations of Canaan must be utterly obliterated. Had we obeyed this command, the argument went, we wouldn’t be in this pickle.

This outlook explains why Ezra was so insistent that the people returning from Babylonian captivity must divorce their foreign wives.

Not everyone agreed. When God chose to spare the people of Nineveh, the prophet Jonah was outraged. He had been hoping for the kind of massacre God visited upon the citizens of Jericho, but God let him down.

If the scholarly consensus is right, the genocidal ambitions attributed to Joshua reflect the agony of weakness, not the arrogance of power. The people of Israel had watched helplessly as their children and fragile grandparents died by starvation and the sword. They stood by helplessly as Solomon’s temple was ground to powder. The book of Lamentations captures the languishing spirit of the times powerfully.

So does the closing stanzas of Psalm 137:

O daughter Babylon, you devastator!

Happy shall they be who pay you back

what you have done to us!

Happy shall they be who take your little ones

and dash them against the rock!

Churches as safe places for hard questions

The suggestion that the text of Joshua doesn’t reflect actual history tends to produce two equal and opposite reactions. Skeptics take scholarly opinion as validation; conservative Christians recoil in horror. If we can’t trust Joshua, they cry, why should we trust anything we read in the Bible?

Few preachers, even in relatively progressive churches, would resolve the Jesus-Joshua problem by questioning the historicity of the sacred text. Similarly, few religious thought leaders are willing to address the radicality of Jesus. Whenever possible, we are encouraged to be kind and forgiving. But the radical implications of loving our enemies receive, at best, superficial treatment.

“We conduct guided tours of the Bible that steer clear of the rough neighborhoods.”

We conduct guided tours of the Bible that steer clear of the rough neighborhoods. Neither Jesus nor Joshua is taken seriously. But when faithful Christians resolve to read the Bible straight through, the Jesus-Joshua problem can’t be avoided. The God of Joshua and the God of Jesus simply cannot be reconciled, and yet both are clearly present in the text. Those who take the Bible most seriously are left to wrestle with the Jesus-Joshua problem on our own.

As a consequence, millions of American Christians wander in the wilderness between a cool skepticism and a fearful biblicism. Unable to harmonize the Jesus-God with the Joshua-God, we end up worshiping an insipid deity who asks little of us. My problem isn’t primarily with the skeptics and the biblicists; both reactions are perfectly understandable. But what of those of us who can’t find a home in either camp?

Here’s the thing: We can’t commit to the enemy-love of Jesus until we’ve come to terms with Joshua. Is there a place in the church for these hard conversations? I hope so. Because, if we can’t talk about this stuff, the Jesus-Joshua problem is bound to get worse.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.