Someone I know was killed by the police.

When a friend from college texted asking if I saw that a former football player at our alma mater had been killed, my stomach dropped. Could it be someone I knew?

Jakob Topper

I went to undergrad at Hardin-Simmons University, a small Christian school in Abilene, Texas. Not so small that everyone knew each other, but small enough that everyone knew of each other. And the weight room was even smaller.

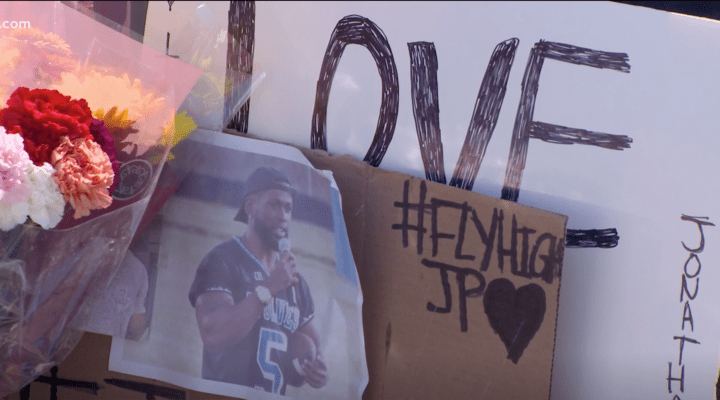

I dropped what I was doing when I got the text, did a quick Google search, and collapsed into my chair when the photo of Jonathan Price filled my screen.

According to witnesses, a white man was beating his wife at a gas station. Jonathan intervened in the altercation, just the way my dad would expect me to do. When the police arrived, an officer saw a white man and a Black man fighting and shot the Black man once in the chest and twice in the back, killing Jonathan. The officer was arrested and charged with murder.

I can’t say Jonathan was a close friend. I had class with him and worked out with him, but we hadn’t spoken in a decade. Yet, the emotional weight of the news was still debilitating.

If this is how I feel when someone I knew years ago is killed, then how must Black people feel each and every time an unarmed person who looks just like them is killed by the police? Many things raced through my mind after absorbing the news, but the one thing I never wondered was whether or not it could happen to me.

My first impulse was to call my Black friends and beg them never to intervene when white people fight. I wanted to plead with them never to wear a hoodie in public or to go for a run in their neighborhood. As if this might protect them from the penalty of blackness in America. As if Breonna Taylor wasn’t asleep in her own home. As if Stephon Clark wasn’t in his backyard.

When reporting on Jonathan Price’s killing, news agencies latched onto a Facebook post he had made voicing his support for police amidst the Black Lives Matter movement. He clarified that he wasn’t saying Black lives didn’t matter, only that he hadn’t experienced the racism the BLM movement was protesting. But even Jonathan’s support for blue lives couldn’t protect him from them.

As a pastor, I’ve said Black lives matter in the pulpit for the last three years. I’m late to the struggle and at a loss about what to do in the face of the mechanical monster that is racism in America. What has allowed me to live for 30-plus years and still not know how to confront racism? I’ve settled with doing the very little I do know how to do until I learn how to do more.

After Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were killed this summer, I once again preached about why I say Black lives matter. I serve as pastor of a church in Oklahoma, so it’s not surprising that there was pushback. What was surprising, though, was that these same people didn’t protest when I said it last year or the year before. Why was this time different?

One of the members who eventually left the church explained that this time they felt like the church was too fragile to be tackling social justice issues. And there is some truth in what they said. My church is in a difficult season, as most churches are right now. On top of the pandemic, the civil rights movement, and the hyper-partisanship, we recently buried a member who was the backbone of our church and whose generosity was responsible for a significant portion of our annual budget.

“How are we going to attract new members and new givers in Oklahoma with you preaching about social justice and left-wing politics?”

“How are we going to attract new members and new givers in Oklahoma with you preaching about social justice and left-wing politics,” they asked?

Not an entirely unfair question. I believe it was driven by genuine concern for the future of our church. And ultimately, I believe they left not because they are racists, but because they thought my speaking out was hurting the church.

Since then, I’ve thought a lot about whether or not their assessment is accurate. Is my speaking out against the treacherous systems of injustice that endanger Black lives hurting my church? People have left. We are financially strapped, and new people aren’t joining our church during the pandemic. Are we too fragile to speak to these issues right now?

I hope not, but unfortunately, only time will tell.

What time already tells us is that Black lives and the lives of people of color are at risk today.

A great many white people just like me are quarantined from the pandemic of racial violence and its devastation. Because we have so few friends of color, and because we know them primarily on our terms and in white spaces, we are tragically under-educated about racism and its effects on the lives of our friends. The temptation we face as white Christians is to value the lives of the institutions we know over the lives of the Black people we don’t know. Many don’t even realize that’s the choice we are making.

We haven’t been told enough that our church isn’t The Church, and that the kingdom of God is where our ultimate allegiance belongs.

When I saw Jonathan’s photo on the front of that news article, racial violence hit me in an entirely new way. Someone I knew is dead, even though I didn’t know him well. It’s only by an act of pure grace that people of color aren’t infuriated every moment of the day that white Christians are still not 100% on board. They know in their bones and through experience what we are still struggling to comprehend in our minds and through books.

“Today I feel more accountable for the lives of my Black friends than the feelings of my white congregants.”

And whether it is right or wrong, today I feel more accountable for the lives of my Black friends than the feelings of my white congregants. God forbid that my feeble attempts to be a Christian make me a poor pastor or that my striving to be an anti-racist endangers my church.

Deep down, I believe this is what my church and my congregants need from me the most, even when we are fragile. But if I’m wrong about that, and I could be, then I think it’s what the kingdom of God wants most from me and all of her citizens.

Our churches, as beautiful and beloved as they are, are still not The Church. The kingdom of God will triumph no matter what.

Black lives matter. Black lives matter more than white institutions. Churches willing to build on such a foundation will have a place in the new world that Christ is building.

#JonathanPrice

Jakob Topper serves as pastor of NorthHaven Church in Norman, Okla.

Related articles:

Too many pastors are falling on their own swords

Three reasons Black well-being falls below others in the latest Gallup polling

Black lives matter to me. Tragically, they mattered little in my segregated upbringing